I recommend Cosmopolis, David Cronenberg’s adaptation of the 2003 Don DeLillo novel of the same name, in the spirit that I might recommend Scandinavian-style salted licorice. It won’t be to everyone’s taste, to put it mildly—even some Cronenberg devotees may be turned off by this movie’s icy, cerebral quality, its aggressive oddness. But at least it doesn’t taste like anything else out there. Cosmopolis (Cronenberg’s first film since 1999’s eXistenZ for which he is sole author of the screenplay) can be maddening in its slowness, its reliance on dense, hyperstylized dialogue, and its casual dismissal of traditional story structure. But it’s also bracing in its unapologetic engagement with language and ideas, not to mention with global economic reality.

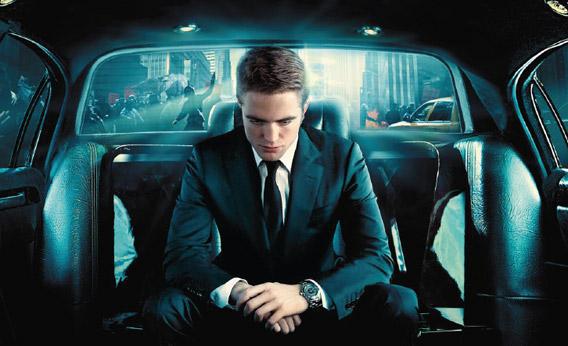

Granted, the “reality” in which this vaguely futuristic fable takes place isn’t quite recognizable as our own. Rather, Cosmopolis’ world is a nightmarish extrapolation: In Cronenberg’s vision, the ever-deepening gulf between the 1 percent and the 99 percent has become an unsoundable abyss. The world is collapsing in chaos, with the poor rioting in the streets as the rich glide past in heavily defended stretch limos. (“The rat has become the unit of currency,” reads the film’s epigraph, a quote from a poem by Zbigniew Herbert that ably captures this movie’s cutting black humor.) One of the most spectacularly tricked-out of these limos belongs to Eric Packer (Robert Pattinson), a 28-year-old quazillionaire whose boy-wonder status is already being threatened by even younger finance impresarios. Eric’s white stretch limo isn’t just bulletproof, it’s cork-lined (or, as he insists on saying, “Prousted”) to block out the muss and fuss of social unrest. But the cork lining proves ineffective: Over the course of this movie’s roughly 24-hour timeframe, Eric’s mobile sanctum sanctorum grows increasingly permeable, as he’s visited by a revolving parade of hookers, hired advisers, and a horde of screaming protesters wielding a giant stuffed rat.

Though Eric Packer does eventually leave the car for a few on-the-ground encounters, including a haircut from his childhood barber and a visit to the grubby lair of a Dostoyevskyan would-be dissident (Paul Giamatti), most of Cosmopolis takes place in the sleek, black, high-tech void of that limousine, with stock-tickers providing an ambient flicker as the characters exchange staccato, deliberately opaque DeLillo-speak, which is not unlike Mamet-speak with a degree in semiotics. “Money has lost its narrative quality, the way painting did over time,” observes a character identified as Packer’s “chief of theory” (Samantha Morton); she might also be talking about the movie she’s in, which veers steadily toward pure abstraction. Another employee, Packer’s financial adviser (Emily Hampshire) jumps in the limo in the middle of her nighttime jog to offer similarly cryptic counsel; in the movie’s bravura WTF scene, Packer solicits her fiscal advice while submitting to, and audibly enjoying, a prostate exam from his doctor. (Though there’s no graphic sex or nudity, Cosmopolis does contain several sickening bursts of unexpected violence.)

Much of your reaction to Cosmopolis may depend on how you feel about Robert Pattinson, the 26-year-old British actor whose role as the abstinent vampire dreamboat of the Twilight series has made him an international object of fan desire (and, since he was publicly cuckolded by his co-star Kristen Stewart, of tabloid sympathy as well.). Yes, Pattinson’s combination of porcelain-doll good looks and narrow expressive range can make him seem vapid, his line deliveries wooden—but what better affect for a character like Packer, a master of the universe so callously remote from the world around him that he barely qualifies as human? Giamatti’s character, the sweaty, hovel-dwelling Benno Levin, summarizes his principled objections to Packer’s existence concisely: “You are foully, berserkly rich.” Casting Pattinson—an actor who’s also a globally recognized commodity—as a character who represents, in essence, the terrifying future of capitalism was a bold conceptual gamble on Cronenberg’s part. In some scenes, the bet pays off, especially when Pattinson is paired with a similarly sleek, remote actor (like Sarah Gadon, who plays Packer’s WASPy new wife with an Arctic chill). But when he plays opposite someone who brings the crackle of real human life to the screen—like Giamatti, who’s astounding in his one extended scene, or Juliette Binoche, who flits through too briefly as Packer’s melancholy middle-aged mistress—Pattinson’s limitations are on plain display. This mismatch in performance styles may all be part of Cronenberg’s grand plan, but it nonetheless creates an alienation effect that makes this 108-minute movie feel considerably longer.

In a live interview he and Pattinson did with the New York Times’ David Carr, Cronenberg suggests that viewers not seek to understand everything that’s happening in Cosmopolis, but instead just let the movie wash over them as an experience, the way flows of global capital—the falling dollar, the rising yuan—stream by on the screens that surround the film’s empty, anxious anti-hero. Because I’ve long been captivated by Cronenberg’s keen intelligence and highly personal cinematic vision, I took a strange pleasure in submitting to this movie’s stilted but weirdly poetic rhythms. But I freely acknowledge that for others, enduring Cosmopolis may be less fun than a backseat prostate exam.