Sarah Polley’s second film, Take This Waltz, is a movie I’ve been awaiting with great anticipation. Polley’s debut film, Away From Her (2006), established the then-27-year-old Canadian (who has been a working actress since the age of 4) as a kind of directing prodigy. Away From Her didn’t feel like a first movie either in subject matter or in style: The story of a vibrant woman slowly losing her mind to Alzheimer’s disease, it was a mature, meditative, exquisitely observant film in which Julie Christie gave the performance of a lifetime.

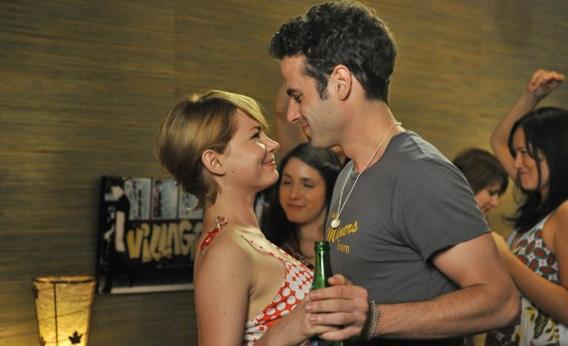

If anything, Polley’s second film feels more like a first. The story of a love triangle among twentysomethings in downtown Toronto, this movie is a shade less original and assured than Away From Her, with a misstep here and there in its pacing and tone. But Take This Waltz still left me convinced that Polley (who both writes and directs) is a major talent with great films ahead of her. This romantic drama, starring the always-extraordinary Michelle Williams as a restless married woman contemplating an affair with her neighbor, is chock-full of individual moments of great power and beauty, including visual beauty: Polley’s camera pays close attention to color, composition, and detail, and Williams has never looked lovelier.

Take This Waltz also takes a wider perspective on the human experience of love than most movies of its kind: The question driving the narrative isn’t only “Which of these two guys will she end up with?” but “In the end, will it matter?” In addition to being a snapshot of three very specific people’s interactions at a specific moment in time, the film is a meditation on time and how its passing alters the nature of romantic relationships and everything else. I wish Polley had taken more, well, time to explore this idea—it doesn’t really kick in until the very end, making the movie’s coda feel like it should be either 20 minutes shorter or 20 minutes longer. (I’d have preferred the latter.) But I admire Polley’s intellectual ambition, her unapologetic conviction that romantic love and domestic life are things that matter enough to think about.

After an unnecessarily rom-com-style meet-cute at a Colonial re-enactment park, Margot (Williams) and Daniel (Luke Kirby) see each other again when they’re seated together on an airplane, and they immediately fall into a strange, intimate conversation that’s both emotionally raw and smolderingly flirtatious. They share a sexual-tension-filled cab ride home from the airport, and only as the car pulls up to her front door do they each share an important piece of news: She’s married, and he lives across the street from her. The story beat in which both realize what an awkward situation they’ve just gotten themselves into is a perfect cap on the film’s first act, spare and rueful and funny.

Over the next few months, Margot and Daniel keep running into each other, at first by accident but increasingly on purpose. Nothing physical happens between them, but Margot is racked by guilt anyway: Drinking martinis with a man at 2 p.m. while he describes in frank detail how he’d kiss his way down her body is clearly not husband-sanctioned behavior. And Margot’s husband, Lou (Seth Rogen), an aspiring cookbook author, isn’t a bad guy: A little oafish and insensitive, maybe, but honest and funny and clearly crazy about his anxious, high-maintenance wife. Margot and Lou’s rapport, which is dominated by baby talk, wrestling, and in-joke badinage, is nicely delineated in the script. Movie portraits of marriage don’t often show us how even a struggling couple can make one another laugh. Or, for that matter, how patterns of communication that were at first playful can become compulsive: What happens when you can only communicate in baby talk and jokes?

I won’t give away any more of what happens among Margot, Daniel, and Lou, since as mentioned above, this movie’s suspense hangs not just on the question “Will she or won’t she?” but even more powerfully on the tougher-to-answer “Why did she or didn’t she?” Yes, Polley relies too heavily on emo musical montages, and the character of Daniel—a sketch artist who makes a living pulling a rickshaw— at times goes a quirk too far. But I’ll just describe a few things from Take This Waltz that will stick with me for a long time: Michelle Williams’ face as she sits next to her not-quite-lover on a carnival ride, each change of the colored lights revealing a different emotional shading: fear, loneliness, joy, lust. Watching Seth Rogen stretch beyond bromance to create a genuinely complex, affecting character, or Sarah Silverman, in a small but pivotal role as Lou’s alcoholic sister, show surprising chops as a serious actress. Or a stunningly planned and executed 360-degree shot near the film’s end that slowly circles a room as it, and its occupants, change through time—a kind of visual equivalent of the vertiginous temporal shifts Virginia Woolf could pull off so well in her fiction. I hope Sarah Polley is writing her next movie already.