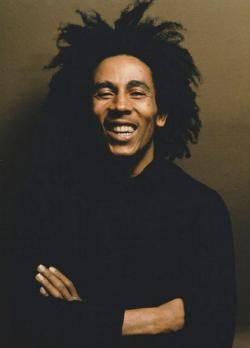

A documentary about Bob Marley executive-produced by his son Ziggy sounds guaranteed to be pious, respectful, and dull. Families tend to overcurate the image of their deceased loved ones even when they aren’t world-famous figures, and Marley, a magnetic, impossibly handsome, supremely gifted singer and songwriter who died of cancer at 36 just as his star was rising internationally, makes an irresistible candidate for dreamy-eyed idealization. This meticulously researched tribute from Kevin Macdonald (The Last King of Scotland, Touching the Void) doesn’t wholly sidestep the pitfalls of the authorized musical biography. Macdonald is indisputably seduced by the singer’s charisma and dazzled by the natural beauty and cultural richness of his native Jamaica. But the director also doesn’t gloss over what he learns about the driven, insecure, and sometimes heartless man behind the legend—even if both the good and the bad Marley remain enigmatic enough to seem always just out of our reach.

Marley might be best described as an oral history rather than a documentary. Chronologically organized and voiceover-free, the movie is a 145-minute patchwork of old concert footage and talking-head interviews—lots and lots of them—from people who knew, loved, and worked with the reggae giant. We hear from Bob’s first schoolteacher, who remembers teaching the already musically inclined little boy his earliest songs—she offers a charming a capella rendition of his favorite, a little ditty about a donkey eating a thistle. Then there’s Marley’s mother, who recalls being 16 when she hooked up with Norval Marley, a sixtysomething white Jamaican and member of the English army, who would father her illegitimate child. Because of his biracial heritage, the young Bob was socially shunned both by his mother’s extended family and the wife and children of his father, whom Bob only saw a few times in his life.

It wasn’t until Bob and his mother moved to the impoverished Kingstown slum of Trenchtown when he was 12 that he began to find his people—musicians like Desmond Dekker, with whom Bob first began playing the shuffling, rock-and-blues-influenced dance music then called “ska.” The interviews about this period, given by collaborators like Marley’s bandmate Bunny “Wailer” Livingston and the owner of Island Records, Chris Blackwell, are among the movie’s best, with Bunny offering a rhythmic breakdown of the one-two-three-four beat that gives both ska and reggae their characteristic loping bounce. Back-to-back clips of Dion and the Belmonts crooning “Teenager in Love” and Bob and his friends’ ska-inflected “do-over” of the same song illustrate how carefully Marley was listening to the American pop of the time, and how consciously he was trying to synthesize that sound with Jamaican musical styles.

It’s also in the Trenchtown scenes that we begin to get a sense of Marley’s boundless ambition—he quit high school to devote himself full-time to writing and playing music, and encouraged the college-bound Bunny to do the same—and his near-fanatical devotion to the Rastafari faith, to which he converted in early adulthood. Macdonald’s movie makes time for an unhurried and fascinating digression on the significance of Rastafarianism to post-colonial Jamaica, including some black-and-white clips from the 1966 visit to Jamaica by the Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie I, whom Rastafarians worship as the second coming of the Messiah. (Selassie’s aide recalls how, upon stepping off the plane to glimpse the vast, roaring, ganja-smoking crowd, the emperor got back in the plane and had to be persuaded that it was safe to disembark.)

In Trenchtown, Bob would meet Rita, the woman who would become his wife, singing partner and, as she wryly puts it, “guardian angel”—a job whose requirements involved shooing overzealous groupies out of Marley’s dressing room, as well as looking the other way while, as his stardom in Jamaica grew, he helped himself to whatever woman he wanted. In all, Marley would father 11 children with seven different women. A few of his former dalliances are interviewed here, including Cindy Breakspeare, the earthily frank Miss World 1976, and a lady identified as “Pat Williams, baby mother.” Williams, asked why so many women threw themselves at the notoriously shy Marley, fixes her off-camera interviewer with a deadpan gaze and says, “Oh my God. You don’t know Bob? That is a handsome guy.”

It’s in the portrait of Marley as family man that this generally laudatory documentary is at its harshest. Ziggy Marley, a reggae star in his own right, recalls his childhood with a beatific smile that contrasts with his less-than-warm memories: “He wasn’t that daddy who would say ‘oh, be careful, son.’ Him was a rough man, you know? Rough, rough, rough.” A more overtly ambivalent daughter, Cedella, remembers how most of the children’s games with their father took the form of fierce, no-holds-barred competitions: “It was always about racing to see who could beat him.”

Marley’s drive to be the best at whatever he did—which, the film implies, derived not only from his origins in poverty, but from a lifelong sense of insecurity about paternity and racial belonging—would eventually be a factor in his death. When a malignant melanoma was found on his toe, Bob refused to amputate the toe for fear he would no longer be able to play in his beloved mid-rehearsal soccer games. A few years later, he would collapse after a concert and return to the doctor to discover that the cancer had spread to virtually every organ in his body.

The end of Marley’s short life was unbearably sad, as is the last half-hour of this film, in which we see snapshots of a wizened Bob bundled against the snow at the remote Bavarian clinic where he spent the winter of 1980 in a last-ditch grasp at an alternative cure. Eventually he would be flown back to Miami to die, without ever making it back to his beloved compound on Hope Road in Kingston.

The thoughtful and leisurely paced Marley is an exemplary music documentary in almost every way—but the area in which it falls short is an important one. Like a surprisingly large number of films about musicians (whether biopic or documentary), this one is curiously resistant to letting the audience hear its subject’s songs in their entirety. One of the rare exceptions—a gospel-style demo of “No Woman, No Cry” with Peter Tosh playing piano, which Macdonald allows to play at length over an aerial shot of Jamaica’s green mountains—is breathtaking. Otherwise, Marley’s music tends to be heard in frustratingly brief bursts, either to illustrate points the interviewees are making or to provide ambient background sound under their voices.

Only during the exhilarating final credits, in which people from all over the world—India, Turkey, Brazil, Japan—sing and dance to their own improvised versions of “Get Up, Stand Up” and “One Love,” does the audience get a chance to really experience the lasting power of Marley’s music. In the 31 years since their creator’s premature death, we suddenly realize, those serious songs about joy and joyous songs about pain have become a part of the world’s cultural patrimony.