It’s hard to feel morally elevated when you’re also feeling talked down to, which is why a couple of movies worthy of the Nobel Peace Prize, Crash (Lions Gate Films) and Kingdom of Heaven (20th Century Fox), are also worthy of the Razzies. Kingdom of Heaven is an epic about Christian crusaders who happen to be liberal humanists willing to die for the sake of religious tolerance. That’s just … weird. Crash is somewhat more grounded. It might even have been a landmark film about race relations had its aura of blunt realism not been dispelled by a toxic cloud of dramaturgical pixie dust. The movie is an ensemble drama set in L.A. and in the style of Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia. Characters rudely collide with other characters in multiple and crisscrossing plots. The theme is racism. Let me say that again: The theme is racism. I could say it 500 more times because that’s how many times the movie says it, in every single scene. Paul Haggis, the director and co-writer (with Bobby Moresco), did the screenplay for Million Dollar Baby, and he thinks like a pugilist. He softens you up with a series of blows to the head, then he pummels your gut, and, in one scene (little girl, stuffed animal, gun), he hammers you a few inches lower. Haggis is so relentless that you have to laugh. But you might also be transfixed, because the cast of great actors is going full-throttle, and the film makes such a gaudy show of its own momentousness.

In the opening, the camera prowls over the site of a car crash (racial epithets abound), while a homicide detective (Don Cheadle) narrates. What’s missing in L.A., he says, is the sense of touch: Everyone is always behind metal and glass. Then he says, “We crash just so we can feel something.” I know it’s a metaphor but it still made me groan. From the hilltop drive, Cheadle gazes at the twinkly/blurry lights of L.A. to the accompaniment of Mark Isham’s shimmery synthesized keyboards, and you just know you’re going to see a lot of lonely people lashing out at a lot of other lonely people—just to feel something.

After the overture, Haggis cuts to the hip-hop artist Chris “Ludacris” Bridges and Larenz Tate as two young black guys strolling down an affluent white city block. Ludacris holds forth on the outrageous racist fear that white people have of black men. Then he pulls out a gun and carjacks a fancy SUV belonging to Brendan Frazer and Sandra Bullock. Fraser plays the callously ambitious L.A. D.A.; Bullock is the wife who, as they say, rhymes with rich. At their beautiful house, she is horrified by a Spanish locksmith (Michael Pena) because he has a tattoo and a shaved head. She thinks he’s going to pass keys to his gang. The irony is that Bullock’s character is picking on Crash’s one saint—a man who just moved out of a bad neighborhood after a bullet came through his adorable little daughter’s window, a man who lives to protect said adorable little daughter.

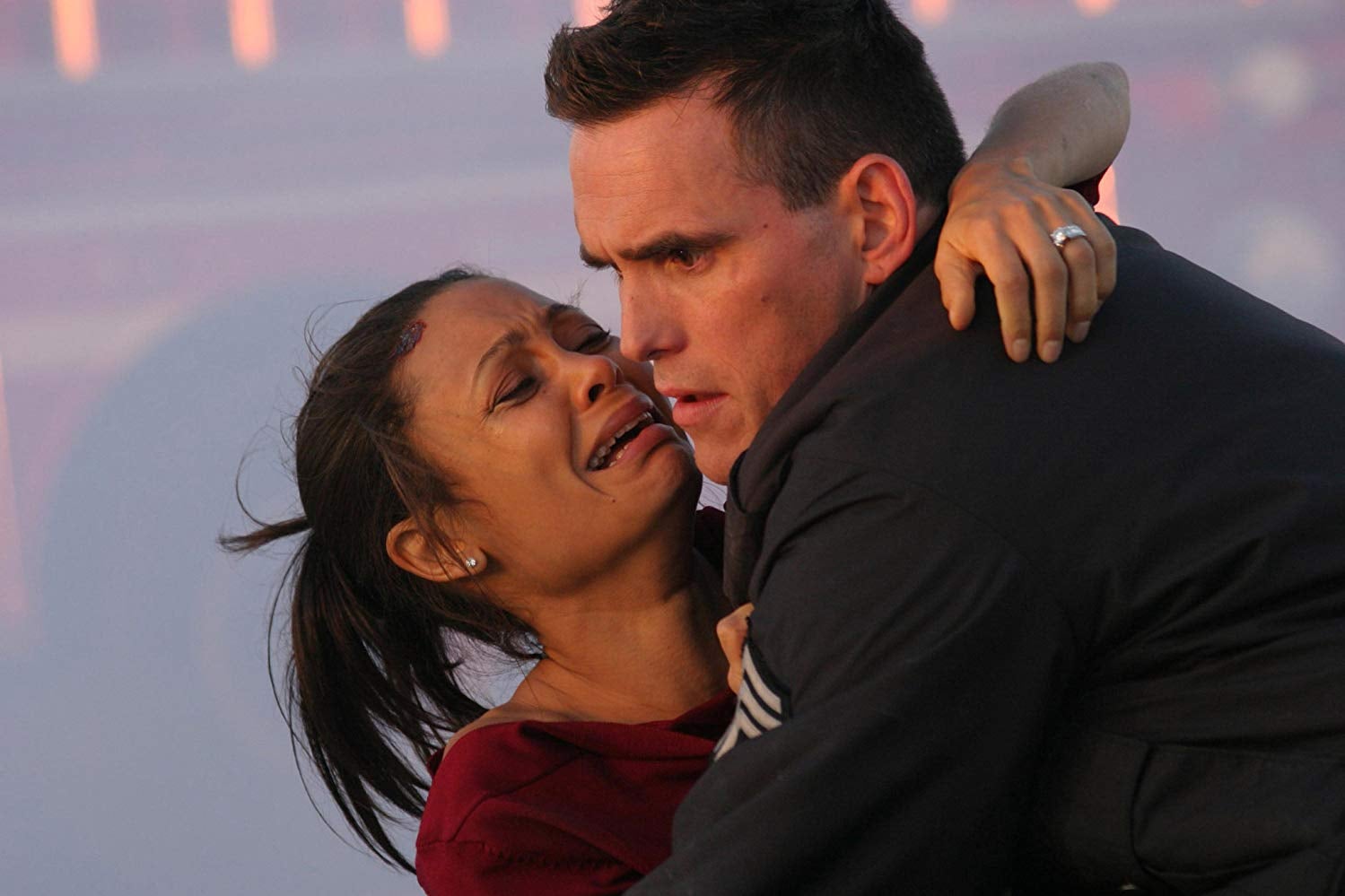

Everyone else in Crash is warped by fear and rage. Matt Dillon plays a cop whose dad is sick and in pain and can’t get an insurance supervisor named Shaniqua (Loretta Devine) to OK a visit to a specialist. Shaniqua: Wouldn’t you know? Dillon hates what he calls those affirmative action hires. So, when he sees what appears to be (and, in fact, is) a woman (Thandie Newton) going down on an African-American man (Terrence Howard) in traffic, he pulls them over. They’re a wealthy couple coming home from a benefit, and the cop savors his power over them. He taunts the man and molests the woman while his partner (Ryan Philippe) looks on in impotent horror.

A few scenes later, Dillon and Newton will be reunited in an incredible—by which I mean not remotely credible—coincidence, and we’ll see that Dillon can be brave and selfless. And Philippe will be reunited in an incredible—see above—coincidence and prove that he can be brave and selfless, too. Then Philippe will meet up with another black man and the outcome will be grimmer. In the end, Crash says, when you push a vicious racist, you get a caring human, but when you push a caring human you get a vicious racist.

All the coincidences—there are more, involving Persian and Chinese families—make for one economical narrative: Haggis wants to distill all the resentment and hypocrisy among races into a fierce parable. But the old-fashioned carpentry (evocative of ‘30s socially conscious melodrama) makes this portrait of How We Live Now seem preposterous at every turn. A universe in which we’re all racist puppets is finally just as simpleminded and predictable as one in which we’re all smiling multicolored zombies in a rainbow coalition. It’s strange, but I came out of Crash feeling better about race relations—not because of anything in the screenplay, but because of the spectacle of all those terrific actors (of all those races) working together and giving such potentially laughable material their best shot. And, really, whites in L.A. are at one another’s throats all the time, too. Kingdom of Heaven, directed by Ridley Scott, is as admirable in its politics as Crash, especially given the fundamentalist climate of the moment. Twelfth-century Christian crusaders/multiculturalists make sterling role models for today’s youth: Bravo! It’s a pity that, historically speaking, they had to exterminate the non-Christian population of Jerusalem to occupy their city on hill, but what are a few hundred thousand Muslims between fanatics?

The movie is honest (or self-protective) enough to acknowledge the schizophrenic nature of its hero crusaders, which only adds to the oddness of the enterprise. The protagonist, Bailian (Orlando Bloom), is a blacksmith, the bastard son of good-guy crusader Godfrey (Liam Neeson). He doesn’t intend to follow his dad back to the Holy Land, but after skewering and then incinerating a priest who taunts him on the subject of his dead wife (long story), he realizes that spiritual purity lies in Jerusalem. Especially attractive is his father’s lack of dogma. Look not to texts, Bailian learns, but to the heart and the mind. Act with rightness. Protect the people.

When Godfrey leaves the arena, Bailian falls in with more like-minded liberal-humanists, among them Tiberias (Jeremy Irons) and Hospitaler (David Thewlis). Bloom is on the stolid side, but the creepiness of Thewlis and Irons (face it, they both look like very dirty boys) gives their gentle, temperate, holy characters a dash of dramatic complexity that isn’t in the script.

The leader of the Muslim armies, Saladin, is a temperate fellow himself, and is played by the film’s (and possibly filmdom’s?) most charismatic actor, Ghassan Massoud. I don’t know where this guy comes from, but he should at very least have his own sitcom. If left to Saladin and the leper king of Jerusalem (Edward Norton, whose face you don’t see), the crusades would have been a real Winnie the Pooh affair—or, at very least, free of the hacking, beheading, and disembowelment party it turned into.

’Twas not to be. The villains—played by Martin Csokas and Brendan Gleeson—are slobbering sadists with French names who say things like, “To kill an infidel is not murder. It is the path to heaven.” They wipe out infidels in order to initiate a Holy War with the more even-tempered Muslims, which gives Ridley Scott a chance to do his computerized extras thing. Scott’s Gladiator had, like, one guy, multiplied by a hundred thousand.

I’d have a lot more respect for Scott if he were actually the virtuoso he pretends to be. Gladiator had lousy, disjunctive action, and Kingdom of Heaven is even more maladroit. Scott uses a strange, accelerated (rotoscoped?) look for his battle scenes, which he mixes with tacky slow motion—for those moments when the audience really needs to know what’s going on. Without the splatter—or, more precisely, the jets of bejeweled blood—the battles would be totally incoherent. Where Scott excels is in single, hot-dog shots, and he has two long-lens desert dillies here: a sunlit cross around which a vast Christian army materializes, and its moonlit Muslim equivalent. Out of such compositions are reputations made.

Some people will see Crash and Kingdom of Heaven and like the politics and, therefore, like the movies, too. But the real politics here are the politics of audience manipulation, which is demagoguery, which is deeply boring, on both sides of the aisle.

Update/Illumination: Having raised the issue of Ridley Scott’s combat scenes (tacky at any speed), I am grateful to Theodore Witcher for the explication. (Of course Scott does not use rotoscoping, an ancient—in cinema terms—process; I was fishing for some modern way of achieving a similar effect.)

Witcher: “Though I haven’t yet seen Kingdom of Heaven, if it looks anything like Gladiator, it’s probably a combination of two things: changing the shutter angle from the standard 180 degrees to 90 or even 45 degrees (for the most pronounced effect) and some form of step-printing.

“Narrowing the shutter angle decreases the amount of time a single frame is exposed to light, which tends to isolate movement more sharply with less blur. In still photography terms (which is referred to in increments of time, like thousandths of a second), this is like the sports photographers who shoot NASCAR and basketball and such and you only see crystal-clear shots of action on the cover of Sports Illustrated. In movie terms, this becomes something of a “staccato” look… think the individual bits of dirt and debris flying up in the opening battle of Saving Private Ryan.

“Step-printing is merely manipulating the formula of twenty-four frames per second. Every other frame, shot at 24 FPS, might be then printed twice, which will yield a “slow-motion” type effect equivalent to shooting at 48 FPS. This is done if a director wants to slow down a shot that was not originally captured in slow-motion, which is an in-camera technique; it will not, however, have the smoothness associated with slow-motion. To achieve an odd look that still runs at 24 FPS, and thus takes the same amount of time to complete, a shot might be made at 12 FPS and then step-printed (every other frame) to 24 FPS. Perhaps this last one is what Scott does in the movie.

“Why he does it, of course, is another matter entirely.”

Why he does it in Kingdom of Heaven: Aye, there’s the rub. Whatever Sir Ridley’s compositional talents, he has always struck me as an inept director of action—that is, until Black Hawk Down, in which the combat was staged and shot in a terrifying, streaky, subjective style that was suited to both the director’s strengths and the material. (The material, of course, is another matter entirely.) The return to the objective—and objectively jumbled—style of Gladiator (albeit on an even larger scale) is positively mystifying.