Early in 1980, Prince Rogers Nelson and his band appeared on American Bandstand, pantomiming the pair of “Wanna” songs that open Prince’s self-titled second album: the disco-funk hit “I Wanna Be Your Lover’” and “Why You Wanna Treat Me So Bad,” an urgently slick rocker whose closing solo can be heard as a survey and apotheosis of ’70s guitar clichés. Young and no doubt hindered by the absurdity of lip-syncing, Prince is less commanding, more nervously showy than he would be a few years later, though he’s already coyly sexy in gold lamé pants, his guitar hanging off his shoulder from a leopard-skin strap. During the between-song interview, Prince’s laconic responses to Dick Clark fall somewhere between sphinxian and childlike. At the start, Clark enthuses, “Man, how’d you learn to do this in Minneapolis?” Prince scratches his head: “Where?” Clark pursues this racially coded line of questioning: “This is not the kind of music that comes from Minneapolis, Minnesota.” Prince chuckles flatly. “No.”

It would have been equally accurate to say this wasn’t precisely the kind of music that came out of Hollywood, where it was recorded, or from anywhere. Other artists around the time—Slave, Donna Summer, Rick James—were coming up with adventurous hybrids of R&B, rock, disco, and pop, but Prince, even before arriving at his full eccentric genius—the eccentric genius he will be remembered for, following his death Thursday at 57—was an anomaly, geographically and universally. Still, his music was deeply rooted in his hometown, its obstacles and opportunities. So how did he learn to do that in Minneapolis?

Like the Kid, his surrogate in Purple Rain, Prince was the son of a musician—in fact two of them: the pianist John L. Nelson and the singer Mattie Shaw of north Minneapolis, the center of Minneapolis’ black community. Nelson was by day a plastic molder for Honeywell, but he played jazz on the side, doing business as Prince Rogers. Shaw was briefly the featured vocalist with the Prince Rogers Trio. There was music, a piano, and eventually an electric guitar in the house, as well as thwarted paternal ambition embedded in the younger Prince’s birth name. Nelson and Shaw divorced when Prince was 7, and the rest of his childhood was somewhat peripatetic. He spent part of his teen years living with a neighbor, Bernadette Anderson, the mother of one of Prince’s key early collaborators, André Cymone. By age 13 Prince was playing in a band called Grand Central, which later mutated into Shampayne and became a prominent act in the local R&B scene Dick Clark couldn’t imagine.

Today, the Twin Cities are growingly heterogeneous, with large Somali, Hmong, and Latino communities, and a black population significantly larger than it was when Prince was growing up. But in 1970, a few years before Prince started playing in bands, there were only 31,400 black people in the Twin Cities metro area, representing 1.7 percent of the population. By the time of Prince’s Bandstand date, that figure was approaching 50,000, but the area’s reputation for notable whiteness, still justified, was then indisputable. It wasn’t an auspicious place to launch an R&B career. Not only did the small black population make it difficult for R&B acts to build sustaining audiences, but the infrastructure needed to make music professionally was underdeveloped, and racism closed many doors. Yet a community of young R&B musicians quietly flourished, a group with wide-ranging, multicultural tastes that would help form the bedrock of Prince’s aesthetic.

The cities offered R&B players little in terms of commercial support. Until 1976, when north Minneapolis’ KMOJ began broadcasting with a soft-pedal signal, only one radio station, KUXL, played R&B with regularity—and it went off the air at sundown. When I was reporting a story on Prince for Mpls.-St. Paul magazine in 2014, drummer Joe Lewis Jr. remembered racing home from school to hear a few hours of music. “You know how short the winter days are in Minneapolis,” he said. “That thing would be signing off at about 5:30.” Those limited options, however, were fundamental to Prince’s development. He long ago told Jon Bream, a veteran Minneapolis Star Tribune pop critic and one of Prince’s great documentarians, that with no R&B airing in the evenings, he would tune into rock stations, where he fell in love with Santana, Fleetwood Mac, and Joni Mitchell, influences he eventually fused with his close study of Sly Stone; James Brown; the Stylistics; Rufus; and other black soul, funk, and rock acts. Many of his contemporaries report the same catholic tastes.

Nightclub opportunities were restricted, too, largely by racism. Though a number of neighborhood clubs hosted R&B acts—and important multiband bills went down at hotels and in parks—clubs in downtown Minneapolis generally shunned black acts, and downtown bars that drew predominantly black or racially mixed crowds were frequent victims of police harassment. With limited promotional avenues from radio and clubs, record production was hardly robust. In the ’50s and ’60s, the national Top 40 often made space for independently produced, regionally hatched hits such as the Castaways’ “Liar, Liar,” a garage classic by teenage Twin Citians. By the ’70s, though, major record labels were more dominant than ever, and indie flukes were rare. Haze, a St. Paul band that presented a braid of soul, rock, and funk in line with Prince’s later eclecticism, made it to No. 38 on the Hot Soul Singles chart in ’74, but its full-length album was stymied by spotty distribution, and a follow-up never came to fruition.

Despite all this, Prince emerged into a small but vibrant, competitive yet nurturing scene of musicians. Some of his formative musical training came at the Way, a politically driven north Minneapolis community center. In addition to classes, meetings, games, and sports, the Way provided space for musical rehearsals and concerts, and its resident band, the Family, were slightly older local heroes to Prince and his cohort. The Family’s agile multi-instrumentalist, Sonny Thompson, later played in Prince’s New Power Generation. Mind & Matter, Cohesion, Flyte Tyme, and 94 East were among the other R&B groups of the period. Most recorded only demos or small-batch records that rarely escaped the skirts of town, but in recent years those efforts have been lovingly compiled by boutique reissue labels: The Numero Group’s Purple Snow: Forecasting the Minneapolis Sound documents the Twin Cities R&B of Prince’s youth, while Secret Stash Records’ Twin Cities Funk & Soul begins in the mid-’60s. Not all of this music is first-rank—the Twin Cities aren’t “isolated,” and of course some of its bands traded in competent but undistinguished imitations of national acts—but much of it is outstanding, and it sometimes displays a restlessness around genre barriers that clearly informed Prince.

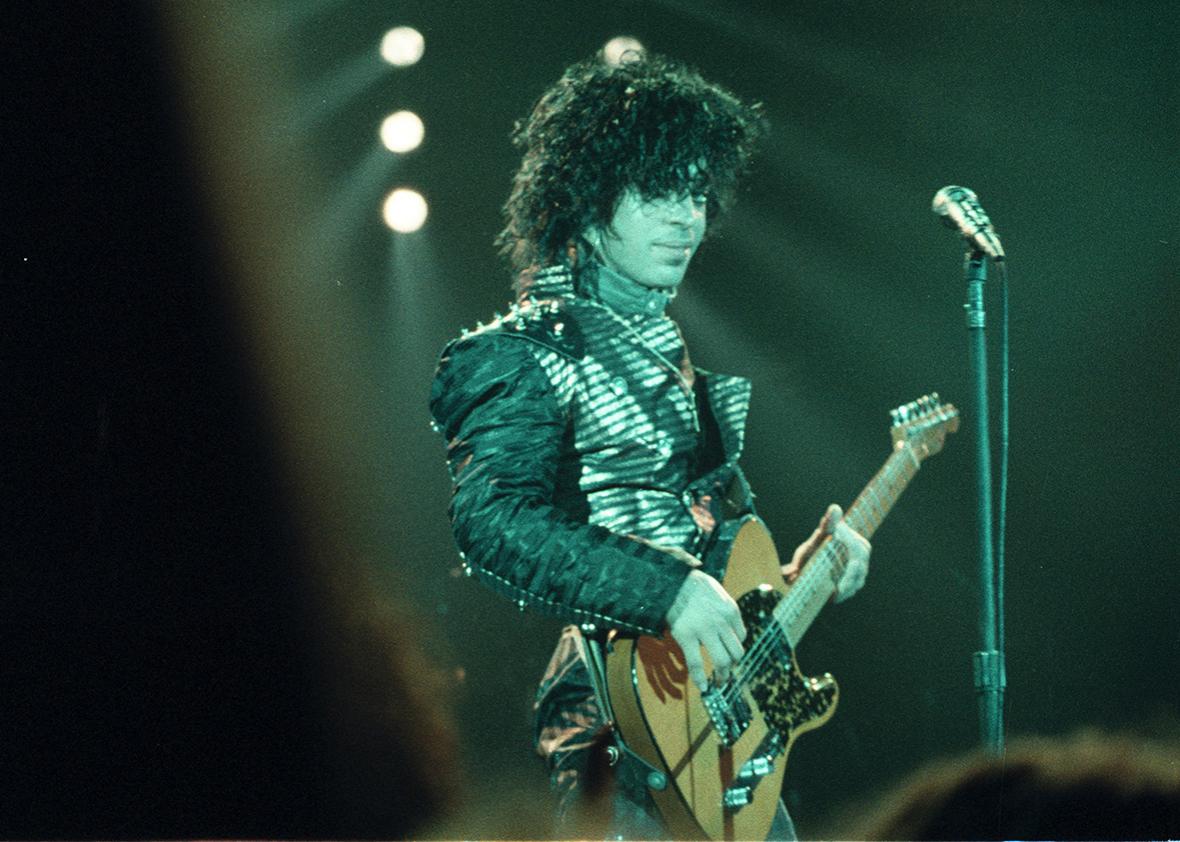

After Prince started to attract attention in Minneapolis, teamed with his first manager, and signed with Warner Bros., his career was for a few years centered almost exclusively in the studio, where he learned to construct remarkably vibrant and interactive performances by recording and overdubbing himself on all the core pop instruments. He didn’t make his local stage debut as a solo act until January 1979, playing with the same lineup seen on American Bandstand at north Minneapolis’ Capri Theater. A larger theater show followed the year after, and along with an arena show there were two pivotal shows at First Avenue, the nightclub where much of Purple Rain was filmed. But unlike his cinematic alter ego, who had a weekly house gig, Prince didn’t regularly perform in the Twin Cities when he was rising from budding fame to superstardom, though he would in later periods.

Early on he did, however, re-establish the Twin Cities as his base, for instance using his Twin Cities home studio to record the groundbreaking Dirty Mind, a collection of ingenious demos that he correctly decided didn’t need L.A. polish and in fact benefited from Minneapolis dirt. Contemporaneous with Prince’s evolution as a recording artist, Minneapolis was developing what would prove to be an enormously influential punk and new wave scene, first led by groups such as the Suicide Commandos, NNB, and the Suburbs, later brought to an apex of ramshackle beauty by Hüsker Dü and the Replacements. Prince didn’t mingle extensively with these groups, but they—and their local audience—helped prod the new-wave impudence and ebullience that surfaced on Dirty Mind and subsequent records. In the end, Prince spent the bulk of his life and did most of his work not terribly far from where he was born. Minnesotans are intensely proud of our native sons and daughters, even those who could not leave town fast enough and never returned. Prince’s loyalty was a constant vote of confidence.

On Thursday in Minneapolis, as the early evening sky filled with apt rain, crowds started to gather downtown to mourn and celebrate. The city closed off the streets around First Avenue, and a taste-making public radio station, KCMP the Current, put together an impromptu street performance and dance. In the club itself, the dance party went all night. When I arrived on Seventh Street a bit after 10 p.m., there were pockets of dancers surrounding boom boxes, people hugging, crying, and taking photos of one another in purple lipstick. I found some friends, all rather dazed and bleary-eyed like me. One was waiting in line to get into the club, in a spot that didn’t warrant optimism about her imminent admittance. Trying to put the loss in perspective, she said, “Almost anything would have been better. They could have taken the Mississippi River.”

After an hour or so, I biked back to my home in Uptown. It’s a rather staid neighborhood, remote from the bohemian Utopia Prince paints in his great song “Uptown”: all that liberationist ecstasy, those full-toned synthesizers, straight-into-the-console guitars, screaming falsetto, “white, black, Puerto Rican, everybody just-a freakin’.” It wasn’t like that then, and certainly isn’t like that now; there’s a Chipotle, a lot of condos. But there’s something else, something in the song and in the air the song has pervaded, a certain love of strangeness and potential.

Prince was protean; there were—there are—millions of Princes, one for each fan. For me, his preternatural virtuosity was imposing but not inhibiting; his larkish faith in the moment—in perfect absences, inspired accidents, arresting convergences, towering harmonies—showed even those of us of modest proficiency that every idea ought to be chased at a gallop, that a good idea is one that feels good tonight, and if it doesn’t feel good in the morning, that’s OK; another one is on its way. He taught me, long before I read such things in books, that sexuality was fluid, that partners should equally give and receive pleasure, that real liberation depends on all of us and is possible. He reminded us that a single artist could use vanguardism as mass culture’s minor seventh, that technical prowess was about dirtily programmed drum machines as much as it was about dazzling guitar fills. I’m proud to have lived near him.

When I got home the sky was clear, the moon was full, and Uptown was exactly how he described it.