It was predictable that YouTube—surely the most prolific engine humanity has ever devised for the recycling, recombining, tributing, and parodying chunks of culture—would soon itself be harvested to produce standalone works of art. I first saw it happen in 2008 with Toronto artist Margaux Williamson’s Dancing to The End of Poverty. By now, YouTube-based installations by artists such as Cory Arcangel or Lebanon’s Akram Zaatari have become gallery commonplaces.

But these are works drawn from the virtuous part of YouTube, its ongoing, creative visual bonanza. They do not dare trifle with the evil side of YouTube: the comments sections.

Everyone knows that unmoderated comments sections are generally toxic dumps that you’d best not wade into unless you want your belief in humanity irradiated into dust. But YouTube comment sections are especially vile, crackling with pent-up rage and degenerating almost instantly into volleys of racist, sexist, and homophobic invective no matter how milquetoast the original video may be. It’s one of the most anti-social of social media sites.

This is largely because YouTube commenting—unlike the kind of ideologically driven misanthropy that news sites attract—is a pastime of adolescence. YouTube belongs to all of us (and is yet another way we all belong to Google) but it is a greater fixation for teenagers: It was over a year ago that a Nielsen study confirmed that American teens were doing most of their music listening there, a fact that made radio tremble and motivated Billboard to recalibrate the way it draws up charts.

It’s helped produce a new golden age of novelty-song hits by Psy and Ylvis and Macklemore, which is one of the many ways that these days recall past transitional pop periods such as the late 1950s or the turn of the 1990s. But it has also seeded the comment-section atrocity fields.

Recently, however, a couple of hardy salvage artists have entered those forbidden zones to unearth what can be reclaimed. First came Montreal writer and filmmaker Mark Slutsky, who created the Tumblr site Sad YouTube about a year ago, starting with a post drawn from the comments on sappy U.K. songwriter James Blunt’s almost unbearably lachrymose 2005 European hit, “Goodbye My Lover”:

R.I.P Harris, we only knew each other for like 2 months, but you were the sickest guy i’ve meet in a while… We weren’t lovers, but now your 6 feet under and i missed your funeral.. sorry bud… ill dedicate some of this life out to you, ….. truth is i feel so helpless, just wating to die.. i wish there was something i could do to change my life..

Harrowing, yes, but not as bleak as the latest Sad YouTube find, posted Monday:

Brought me back to a time where I wish life could’ve stood still & never went forward. I was 13 & in one more year, my sister would be murdered & my life torn apart.

The improbable madeleine that evoked that memory? Exile’s randy 1978 stadium-rock creepy-crawler “I Wanna Kiss You All Over.”

Sad YouTube is full of such juxtapositions, though not all so devastating—many are gentle, bittersweet recollections of parents and grandparents, of lost loves, of coming back from Vietnam or Iraq, and much more. Then there are uniquely touching accounts such as this comment on the relatively obscure 1980s hi-NRG club anthem “Take a Chance on Me” (not the ABBA song):

My parents are staying with us this week. Mom walked into my study when I started playing this. She just stood there with her eyes closed, and tears running down her face. She hasn’t heard this song since she and my Dad were dancing at The Saint, a mostly Gay club in Manhattan, in the Eighties. For a moment she was back there, with so many friends who died in the epidemic not long after. ‘For a minute, it’s like I was actually there, and they were all still alive.’ Thanks for posting this!

On a first encounter it’s tricky to gauge the tone of Sad YouTube, to tell whether, like so much of the Internet, its typos-and-all excerpts offer cheap laughs at other people’s misery. Fortunately, Slutsky has put up a page explaining his intentions and mounting a defense of the “much-maligned” genre of YouTube commentary: “Among the usual hate speech and Obama conspiracy theories, you can find these amazing nuggets of humanity—heartbreaking moments from people’s lives recalled by an old favourite song, stories of love and loss, perfectly crystallized moments of nostalgia and saudade. … I almost feel like you could write a Studs Terkel oral history of America culled entirely from YouTube comments on pop songs.”

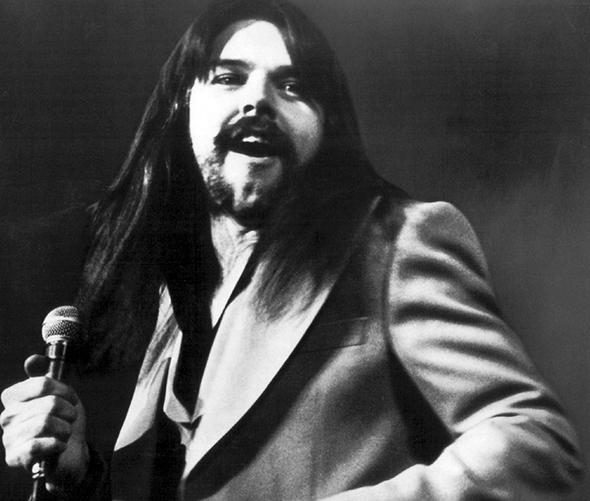

Perhaps so, but you also could argue that Slutsky’s act of culling is paring away something essential to YouTube and even to America: the contentious, clashing, collaborative chaos. Baltimore artist and writer Stephanie Barber goes out of her way to preserve all that in her book Night Moves, published earlier this year: It’s a 75-page transcription of the YouTube comments on a single video, the one for the Bob Seger 1976 FM classic “Night Moves.”

Like Sad YouTube, Night Moves includes many personal recollections, though given the niche and subject matter of the song—boomer rock about teenagers making out in the back of a 1960 Chevy in “the trusty woods”— they tend to be about partying and lust, often with heavy winks from middle-aged posters: “It was a ’79 Plymouth, but yes yes yes. This song always transports me back to Harrah, Oklahoma, the late 1980s, and Jerry Sinor’s night moves. More than 20 years later, nobody has ever kissed me like that.” Or more succinctly: “Got me knocked up in 84.”

But Barber’s montage of murmuring, blurting, and kvetching voices also includes YouTube staples such as shout-outs to whatever movie or TV program “brought you here”—“Night Moves” has been featured on How I Met Your Mother, That ’70s Show, and Top Gear (and, in the months since Barber’s book came out, in Grand Theft Auto V, as you’ll quickly learn if you visit the video’s page today)— followed by debates about whether it is cool or the downfall of civilization that kids today might learn about Bob Seger from a sitcom, then people popping up periodically to quote Liz Lemon’s one-line parody from 30 Rock, “Workin’ on my night cheese …”

Given that this is a classic-rock song, it also occasions repeated fights about whether music today has gone all to hell, some fairly thoughtful and some more on the level of, “You truly are a dick head and that this song goes right over your head is not surprising, you stick with ga ga..”. This leads to another YouTube standard (which Slutsky’s also noted): a poster saying that he or she is a teenager and yet loves this song and hates rap and/or Justin Bieber.

It’s in these alternations between poignancy and repugnance, the tender and the foul-mouthed, the clichés and the arresting confessions, separated by bubbles of white space, that Barber discovers the poetry of the comment section. Her gesture here goes back, of course, to Marcel Duchamp and all the conceptual art since that has been produced by putting a frame around a found object. (She often collages found images into her video work as well.) In literature, there is still resistance to the practice, out of a more old-fashioned attachment to the notion of the author that seems unlikely to survive many more years of the Internet. Night Moves comes with a blurb from Kenneth Goldsmith, the most prominent advocate of what he calls conceptual writing (or sometimes “uncreative writing”)—he has put the entire text of one day’s New York Times between covers as a book called Day, and transcribed a season of weather reports (The Weather) and every word he spoke for a week (Soliloquy).

But where Goldsmith’s works are more to be browsed and contemplated than read, Night Moves is surprisingly a page-turner. It’s the sexuality and the fractiousness and the melancholy about aging (poster after poster cites Seger’s line about “autumn closing in”), but it’s also the way the specter of the song creates a soundtrack, pulsing through the pages, punctuating the lines, rehearsing its macho erotic moves.

This is the insight that both Slutsky and Barber have flashed on intuitively, I think, in choosing the comments on songs (out of all the YouTube offerings): that music, because it can be background and foreground, because it is about sculpting time, often insinuates itself into our lives more in the way that people and events do than in the manner of a movie or a painting. It’s a medium of echoes, inherently conversational. The way that we address it, whether coherently or inchoately, is in turn musical.

So when a new form of talking about music comes into being, it is a bit like a new genre of music being born. That’s especially true of YouTube, where the comments accumulate in a process that mimics “real time,” sprawling out potentially forever (or at least until the copyright holder yanks the video, in which case we can bitch about that). They can be written and read while the song itself plays on, and while untold quantities of people are sharing and exchanging the link on Facebook or Twitter, saying “remember?” or “check it out” or “this is who I am” and “this is who I’m not,” as if we’re all sitting on the carpet of a multidimensional rec room and putting on tunes, then cutting them off in favor of something newer or older, hotter or colder.

No artifact of culture can be stripped of its context, whether collective or personal, and anything that lasts is constantly acquiring associations. But music is particularly social that way, at once as perishable as slang and as renewable as a forest. A song is a story but a sound is a sensation, and all our efforts to criticize it, to stake out a claim, are questionable translations or incomplete harmonies.

The old saw is that writing about music is like dancing about architecture, but writing about music on YouTube is like clambering up on the architecture, hanging banners and family photos on the window ledges, or tossing garbage from the gables. Its anonymity makes it all the more like a group portrait, hauling us into visibility in all our bedraggled need. It’s not that you can’t or shouldn’t formally analyze or evaluate a song, but YouTube’s intimate entanglements make it plainer that doing so is no more the end of the process than gossiping about your family, even to your therapist, is a resolution to the relationship.

It’s the burden of the artist to find the exact place to put a bracket around such segments of reality and the imagination, one that might alter perspectives, and skew our sense of the borders between “virtue” and “evil.” Before following on Slutsky’s and Barber’s excursions, the territories below the videos on YouTube looked to me mostly like benighted wastelands. Thanks to their attention to the novel tones of the moment, though, I can join Bob Seger in singing, “Ain’t it funny how the night moves/ When you just don’t seem to have as much to lose?” Yes, and how the dawn comes on, when you spot new roads to move along.