The following is excerpted from Anatomies: A Cultural History of the Human Body by Hugh Aldersey-Williams, out now from W.W. Norton.

The best sight gag in the entire history of art must be the fig leaf. How large it is! And how very suggestive in its shape! How it engrosses what it purports to hide. How many other plant leaves might have done the job with less blatancy. And yet the fig leaf it assuredly is that artists have elected to use when asked to preserve the public decency. The Bible gives them their cover story: In Genesis, when Adam and Eve realized their nakedness, “they sewed fig leaves together, and made themselves aprons.” But aprons are garments that surely provide rather more coverage than the single, strategically positioned leaf of artistic convention, with its three major lobes simultaneously screening and outlining the penis and testicles behind, and two further vestigial lobes appearing so neatly to represent curls of pubic hair.

The artistic fig leaf became all but mandatory when in 1563 the Roman Catholic Council of Trent ruled that “all lasciviousness be avoided” in religious images “in such wise that figures shall not be painted or adorned with a beauty exciting to lust.” Up until that date, in classical statues and in the Renaissance art inspired by them, false modesty had taken a different form. The human figure was often modelled on the bodies of athletes, who performed their exertions naked. In a monument to a civic dignitary, a philosopher, or a general, a well-toned body was the sculptor’s means of indicating their good citizenship. The artist would carve the genitals on such statues to be somewhat less than life size. Unless the point was to celebrate fertility, as with the conspicuously erect penis of Priapus, the Greek god so eagerly adopted by the Romans, a sculpted penis of normal size, even a flaccid one, was thought vulgar and a distraction from the achievements that it was the business of the statue to celebrate.

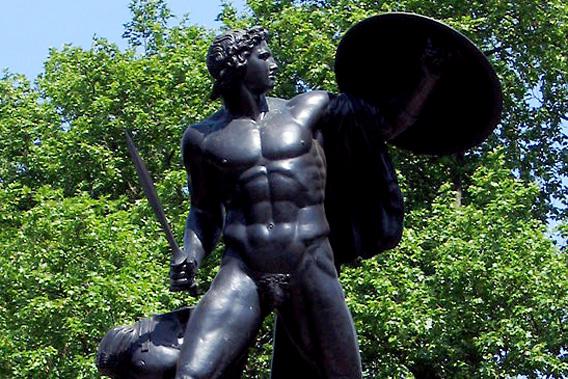

The first nude statue to be put on public display in London since Roman times was the monument raised to the Duke of Wellington not long after his victory over Napoleon’s armies at Waterloo. The sculptor Richard Westmacott created a dynamic bronze figure of Achilles so large that it could not be transported into Hyde Park, where it was to be stationed, without knocking down a wall. The artist had taken the precaution of including a fig leaf, but the leaf—and presumably also any genitals that it hid—was comically small. The caricaturist George Cruikshank was not slow to see the potential. His cartoon of the unveiling shows ladies clustered round the statue, which was paid for by a subscription of British women and “erected in Hide Park,” as the caption explains in a barrage of puns. “My eyes what a size!!” one lady squeals, while another at last locates the salient detail with the aid of a telescope. “I understand it is intended to represent His Grace after bathing in the Serpentine,” another opines. See, one lady tells the duke himself, “what we ladies can raise when we wish to put a man in mind of what he has done & we hope will do again when call’d for!” And inevitably, a small child points to the leaf: “What is that mama.” Immune to such ridicule, the Victorians retrofitted fig leaves to many statues. Even the cast of Michelangelo’s David in the Victoria and Albert Museum sports this extra adornment.

In the art of the nude, man gains symbolic virtue at the expense of personal identity. After all, Westmacott never would have represented Wellington actually naked. Nor would the British public have expected to see their great leader’s actual private parts or even his body replicated in bronze. Woman also loses her identity: She becomes simply “the nude,” the generic of female sexuality and vulnerability. The male nude swaggers through the city streets, keeping public decency with his fig leaf. The female nude is for private consumption, preserving her modesty more coyly in what is known in the trade as the pudica pose—with one hand attempting, more or less vaguely, to cover (or is it directing the eye toward?) the genital area. The specialist word in fact acknowledges this ambiguity, stemming as it does from Latin words for both external genitals and shame.

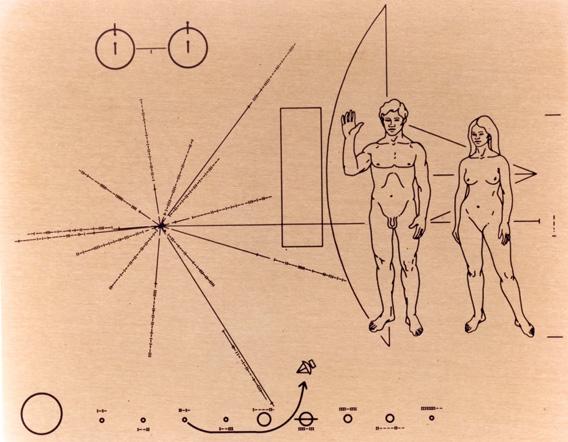

In both cases, we remain uncomfortable about honest depiction of the sex. We have even communicated our prudery into outer space. Michelangelo’s David may have a small penis, but the gold-plated representation of woman sent out far beyond our solar system aboard the Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 space probes in 1972 and 1973 has no vagina at all. Why are we withholding the story of our true physical appearance from other species? Will they puzzle over how we reproduce?

The idea that the spacecraft—the first human-made object intended to leave the solar system—should carry some sort of message about the creatures that sent it was enthusiastically taken up by the space scientist and television personality Carl Sagan. At first, only scientific diagrams indicating our location in the universe and one or two other things that we have discovered about it were to be included. But Sagan’s artist wife, Linda Salzman, suggested that the graphic should also show a man and a woman. The figures are supposed to have “panracial” features, to use Sagan’s word, though Salzman based them on Greek ideals and the drawings of Leonardo da Vinci. But any fashion-conscious alien would immediately note that their hairstyles alone pinpoint them in the late 20th century and imply a Caucasian ethnicity. In fact, so provincial do the couple seem, the man waving in greeting, the woman standing demurely at his side, that a satirical magazine in Berkeley ran the image with the caption: “Hello. We’re from Orange County.” As Sagan wrote: “The man’s right hand is raised in what I once read in an anthropology book is a ‘universal’ sign of good will—although any literal universality is of course unlikely.”

Image courtesy of NASA Ames

The Pioneer plaque excited comment from almost every quarter. Women wanted to know why the woman wasn’t also waving. Homosexuals demanded to know why homosexual partnership wasn’t represented. The art critic Ernst Gombrich pointed out in Scientific American that only aliens with a visual system that operates within the same specific region of the spectrum as our own would be able to see the image.

But the most heated debate swirled around the nakedness of the humans and their visible or invisible sex organs. The two figures stand slightly apart rather than holding hands as initially conceived, so that they are not misconstrued as a single hermaphroditic organism. But other than this subtlest of clues, there is little to indicate that we are a species reliant upon sexual reproduction, which seems a significant omission considering that this phenomenon remains one of the deepest oddities about life on earth. Reprinted in newspapers, the design drew predictable accusations of pornography. The Philadelphia Inquirer took the precaution of erasing the woman’s nipples and the man’s genitals. The Chicago Sun Times progressively amended the versions they printed in successive editions of the day’s paper to obliterate the man’s genitals, too. On the other hand, the incompleteness of the woman’s drawing also provoked complaints of censorship. Sagan defended the omission of a line representing the vagina on grounds of artistic tradition, although it seems that he and his wife took the decision at least partly to head off any difficulties with puritans among the NASA top brass.

Sagan pointed to ancient Greek statuary in particular, although the Greeks created few statues of women other than Aphrodite, the goddess of beauty. For the most part, during both the Classical and neoclassical periods, artists preferred to duck the whole issue by the use of the pudica pose or a strategically draped cloth, but it is true that female nudes made without these devices did, like the Pioneer drawings, generally omit any hint of a vagina. As Sagan himself noted, the real value of the whole episode was to raise the issue of how we represent ourselves to ourselves more than to any other species.

The French 20th-century philosopher Roland Barthes made much the same complaint of incompleteness when discussing Parisian striptease in his Mythologies. “Woman is desexualized at the very moment when she is stripped naked,” he discovers. (We imagine the poor ecdysiast doing her best as the learned semiotician sits in his pullover and tweed jacket, taking notes.) “We may therefore say that we are dealing in a sense with a spectacle based on fear, or rather on the pretence of fear, as if eroticism here went no further than a sort of delicious terror, whose ritual signs have only to be announced to evoke at once the idea of sex and its conjuration.” The fig leaf presents a vegetable barrier to the fleshy, animal sex. The diamanté G-string that is revealed at the (anti)climax of the striptease, Barthes groans, presents an impenetrable mineral barrier. “This ultimate triangle, by its pure and geometrical shape, by its hard and shiny material, bars the way to the sexual parts like a sword of purity.”

We can’t leave it here. John Donne goes all the way in his elegy, “To His Mistress Going to Bed.” All such obstacles are removed one by one in this poet’s striptease: “Unpin that spangled breast-plate, which you wear, / That th’eyes of busy fools may be stopp’d there.” Then, “busk” and gown and hose come off, until at last …

“O, my America, my new found land,

My kingdom, safeliest when with one man mann’d,

My mine of precious stones, my empery;

How blest am I in this discovering thee!”

—

Excerpted from Anatomies: A Cultural History of the Human Body by Hugh Aldersey-Williams. Copyright © 2013 by Hugh Aldersey Williams. First American Edition 2013. With permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.