The hackers we meet in popular fiction tend to be heroes: countercultural underdogs and self-styled freedom fighters typing furiously on their laptops to save the world from tyranny. But a spate of recent independent video games delves into the contentious issues surrounding government surveillance by inviting you to become a very different sort of cyberwarrior: one of the state-sponsored hackers and eavesdroppers whose job it is to invade people’s digital privacy in the name of “national security.”

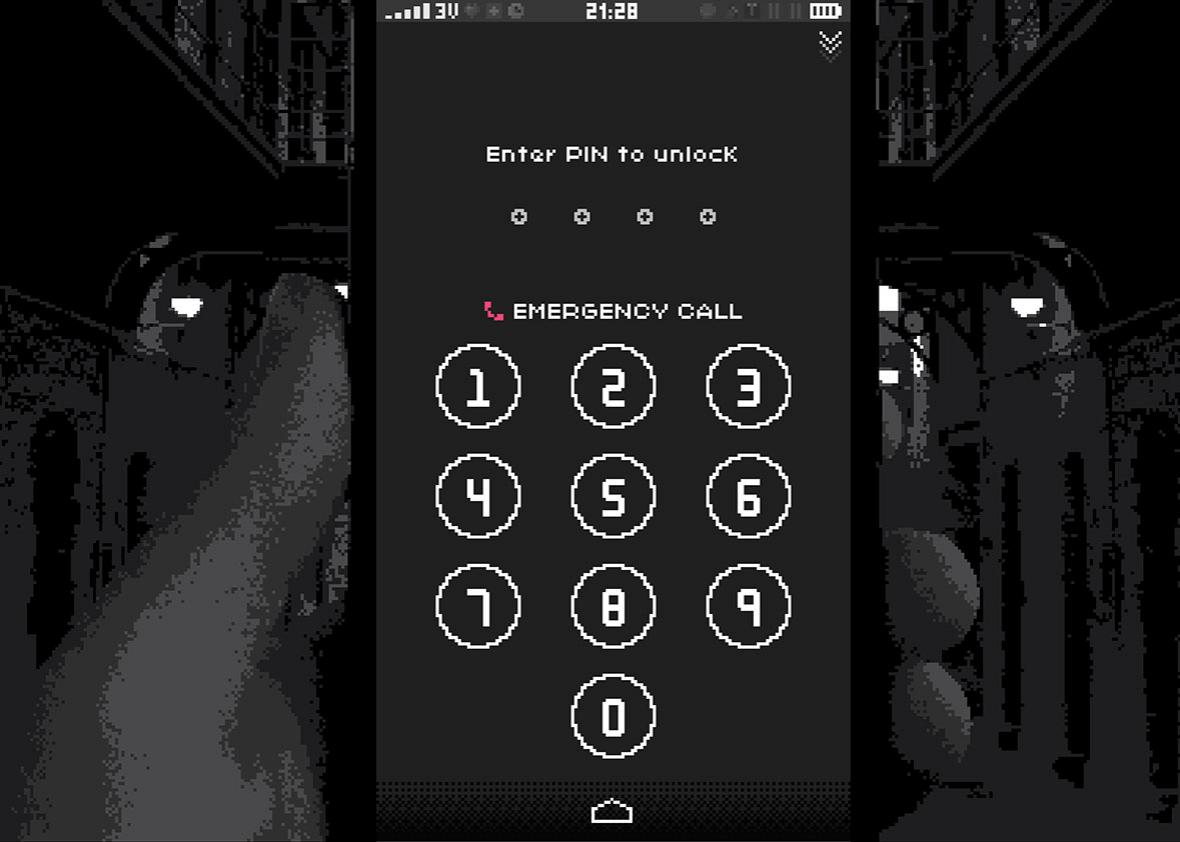

In order to play Replica, a recently released game about state-sponsored hacking, you need a smartphone. Not a real one, mind you, but a grainy, digital facsimile that appears on your computer screen, gripped by an anonymous hand inside a bleak, gray building.

The screen buzzes with a message: The phone belongs to a terrorism suspect, and it’s your job to hack your way into its secret folders and collect evidence to prosecute him. By sifting through his texts, emails, and photos, you learn enough about his life and his loved ones to guess his passwords, and then go digging in his social media and secret folders. As you go deeper, it starts to look like this “terrorist” is merely a mouthy 17-year-old boy, but your handler pressures you to flag more and more of his behavior as suspicious—or even seditious. “Remember, you are now a guardian of liberty for our democratic country,” your handler writes, and somehow it sounds like a warning.

Replica is not a comfortable game, and complying with its instructions feels fraught. The act of playing the game is predicated on invading someone’s privacy in unwarranted ways; “winning” it means ruining his life. It’s an indictment not of the workaday individuals who end up acting as agents of Big Brother, but rather the blind, often monstrous systems designed to circumvent people’s rights in the name of patriotism and security. If games like this demonstrate anything, it’s how easy those systems make it to erode the dignity and privacy of innocent citizens until it all but evaporates.

In the iOS game Touchtone, you’re a newly minted agent at the National Security Agency tasked with decrypting the private emails and text messages of your targets and flagging them as “pertinent” if you believe they contain threats to national security. You hack your way in by solving puzzles, of course, connecting digital signals from one point to another by bouncing colored lines off angled bars. They’re challenging puzzles, and pleasurable ones: When you finally snap the right bar into the right place and the signals connect, they erupt in satisfying waves of color that wash over the screen. Why wouldn’t you want to keep doing this? After all, the more signals you connect, the more communications you get to access, and the safer the country becomes—at least, in theory.

The priorities involved in keeping our nation secure, however, often seem to be skewed. If you flag a conversation by two Wall Street traders plotting to certify bad investment bonds, your judgment is deemed “incorrect”—people in the finance sector couldn’t be real threats, your handler insists. Conversely, fail to flag the texts of two teens bantering childishly about smoking weed, and you’ll get another scolding. “These individuals are obviously involved in drug trafficking,” your shadowy overseer notes. “They must be watched.”

Mikengreg

Eventually, your handler advises you to just start tagging everything you find as pertinent and worthy of more surveillance. Echoing the broad expansion of surveillance powers granted to the U.S. government after 9/11, he insists that this sweeping invasion of privacy is justified by the threat of terrorism. “Remain vigilant,” he warns, “only we have the power to protect the nation.”

Although there’s a certain thrill to digging through a stranger’s private communications or successfully hacking your way past a security system, your work takes on a darker cast when you start to realize that this isn’t just an exercise in voyeurism or puzzle solving—you’re invading people’s private lives and branding them as potential terrorists on flimsy pretexts.

Nor are you safe from the pernicious overreach of the government, just because you wield some small measure of its power. Refuse to surveil your targets or meet your quota for identifying suspicious material, and you may find yourself in the crosshairs instead. In the web-based game AlethiCorp, you apply for a job at an “information management company” and access a faux employee portal where your job is to read surveillance transcripts and flag suspicious behavior. Each day, you’re greeted by reviews from your numerous supervisors on your performance, and unless you expand your definition of “suspicious,” you’re quickly branded a spy and the game summarily ends.

Replica takes an even darker turn, revealing that not only are you attempting to hack into the phone of a terrorist suspect in a nearby cell—you’re a terrorist suspect yourself, and digging up dirt on someone else is apparently the only way to prove that you’re a good, cooperative citizen. “Wouldn’t you like to get your clothes and phone back and see your parents again?” your handler asks ominously as he prods you to snitch on your fellow prisoner.

The most potent indictment of surveillance states and the cannibalistic bureaucracies that feed them comes in the form of Papers, Please, an award-winning game set at the border crossing of an authoritarian country. (Ironically, the game was briefly banned by the Apple Store.) Although the surveillance you perform—fingerprinting, x-rays, examining documents—is more analog than digital, your invasive techniques are a reminder that repressive governments have been playing Big Brother with their citizens since long before the advent of the internet.

Your character is required to monitor travelers and detect terrorists according to a series of arbitrary and ever-changing rules. If it’s difficult for you to keep up, it’s nearly impossible for the people trying to cross the border. Often, you’ll meet people whose papers aren’t entirely in order, but they’re in desperate circumstances: fleeing violence and war, or trying to reunite with lost loved ones. Letting them in against regulations, however, comes with a price. Show too much sympathy and the paltry salary that keeps your family alive will dwindle to nothing thanks to the fines you incur. With so much at stake, it often feels like you have no choice but to send the sad-eyed old woman with forged documents back to a war-torn country where she will probably die.

If there’s one thing that defines surveillance games like Replica, Touchtone, AlethiCorp, and Papers, Please, it’s the slippery moral slopes contained in the systems they simulate. They’re designed to mimic the coercive power of surveillance states in miniature and demonstrate just how easy it is for people to become complicit. By turning you into the Man instead of letting you fight the Man, they reveal the corrosive impact of oppressive political and institutional structures, not just to the liberties of their direct targets but to the values of society at large.

Nor are game developers done mining this particular vein of interactive critique. Need to Know, a computer game about working for an intelligence agency in a police state, is currently available for preorder after raising more than $135,000 earlier this year. Shortly after its announcement, famed CIA whistleblower Edward Snowden posted a link to the game on his Twitter feed. “Art imitates life,” he wrote.