The most surprising thing about the horror games of indie developer Kitty Horrorshow is what you won’t find in them: There are no monsters, no weapons, and generally no people. You can’t even really die. But they’re scary as hell anyway, and all the more frightening because of what they conceal.

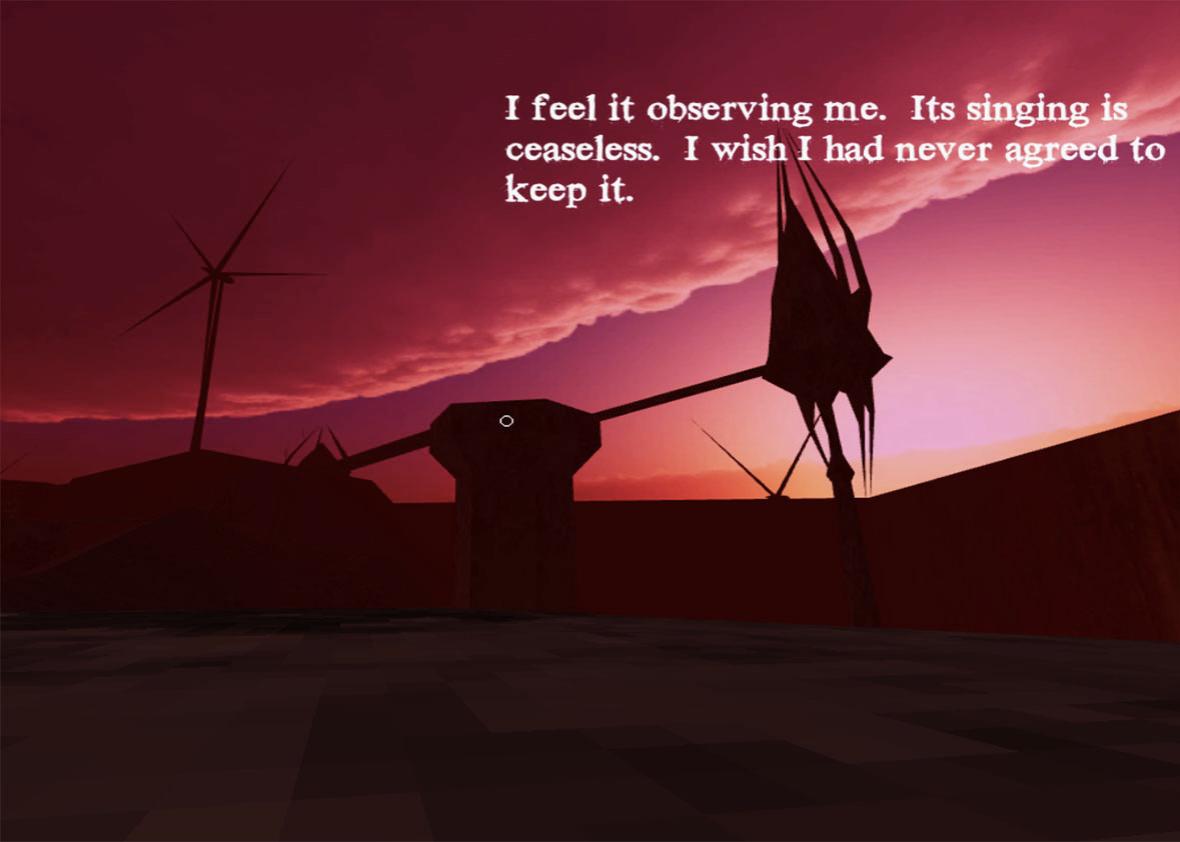

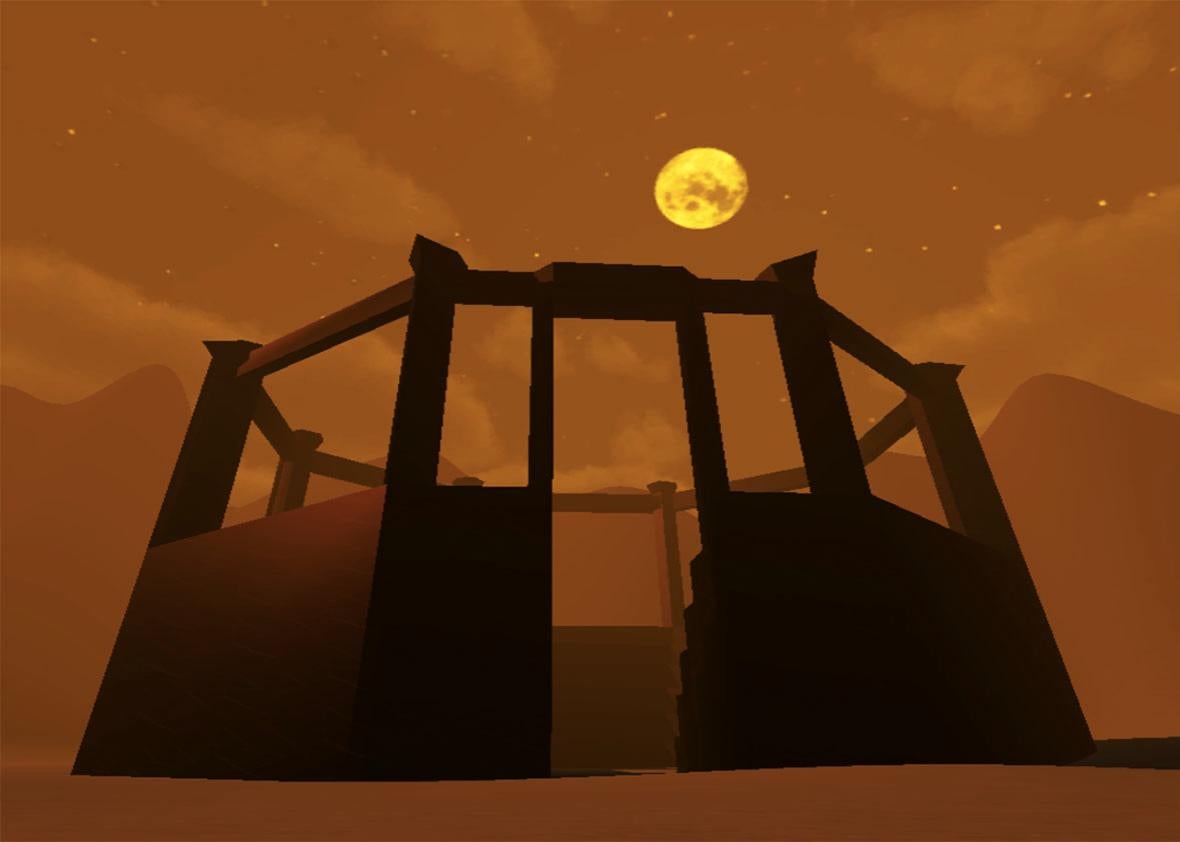

Sometimes dubbed indie video games’ “mistress of horror,” Horrorshow is a first-rate purveyor of dread and suspense whose work experiments with the boundaries of interactive horror in fascinating ways. Her beautiful, dreadful games—which last only 20 to 30 minutes and are typically free—are less about following a linear path through a story and more about navigating a landscape. They open with little ceremony: In Chryza, you find yourself walking across a desert toward looming, impossible monuments of black stone hung in an ochre-stained sky; in Rain, House, Eternity, you navigate a forest of jagged, black trees in rain so heavy you can barely see a few feet in front of you; in Anatomy, you awaken in a crumbling house that beckons you from room to room with increasing malevolence. You don’t know where you’re going, or why, only that you are—and that your destination both attracts and repels.

Each world is scattered with breadcrumbs that draw you from one area to another, that trigger messages or audio recordings when you touch them. Sometimes a light will shine faintly from the distance, a cassette tape will appear in a room you’re sure was empty just moments before, or you’ll see the strange, shadowy form of a mysterious structure looming on the horizon.

“I don’t bother with death or fail states because they don’t interest me,” says Horrorshow. “If a game is focused on exploration and narrative, death is usually the most uninteresting part. But if you’re not going to kill the player, how do you scare them? What is there to be afraid of? What are the stakes? I try to keep it vague and create a sense that something bad is happening or building under the surface.”

As a general rule, big-budget horror games tend to feel a lot like playable survival horror movies with action sequences grafted to their skin, full of interactive monster-shooting but often still captive to the tropes of a passive medium. Horrorshow’s games fascinate by taking advantage of what makes games different from movies or television or books: the ability to embody a character and make choices but also to tell stories through architecture—to design experiences around how movement through space can make us feel and what it can mean.

“The appeal of video games for me is that they put you somewhere,” says Horrorshow. “And that’s something I use to full effect. I like making games and treating them like worlds that have a history, environments that are strange and beautiful and wonderful. I don’t characterize the [protagonist] you play very much. It’s not about them or their story. I want you to feel like you’re the one who’s there. You go there, and you puzzle it out for yourself.”

The dark hallways and winding paths in her worlds often feel slightly longer than you expect as you cross them. Distance becomes a tool of suspense; even if you’re running as fast as you can across a barren expanse of desert, those interstitial moments of transit can distend into an uncomfortable limbo—one that suspends you between here and there, between knowing and not knowing.

Horrorshow’s games do not attack you; their dread rarely materializes in a physical or visual sense. Instead, you feel it as you move through the world: the sense that something terrible is going to happen. It’s a feeling that already haunts the anxious among us, and one that is no less horrifying even if those fears never come to pass.

“I personally find jump scares really unsatisfying,” says Horrorshow. “If somebody raises up their fist to punch me I’m going to get startled, but there’s nothing interesting or edifying about that. It’s just a reflex. A jump scare is when you attack the player; a dread scare is when they have to do something, even if they don’t want to. The difference is [the player’s] role in it. It puts you in the driver’s seat.”

Her latest game, Anatomy, is a haunted-house tale suffused in body horror—except that the house is the body. As you wander through its halls and peer through its doorways, the rooms you find are so dark that you can barely make out a faint outline of what lies ahead. You can find out what’s there, of course, if you’ll be so kind as to step forward into the darkness. These spaces are designed to seduce and discomfit; they beckon you to move through them in ways that are unsettling, unnerving.

The game directs the player to find and play a series of cassette tapes that suddenly appear in different rooms, despite the house supposedly being empty, and play them on a cassette player in the kitchen. You will not always like what you hear. “THERE IS A TAPE IN THE BASEMENT,” the game will tell you at one point. You will not want to go there. But you will. Instead of sending a monster to lunge at you from behind a curtain, Anatomy would rather open a door that leads into darkness and dare you to walk through it.

Aside from the music, Horrorshow makes her games entirely on her own, and there’s a spare, forbidding beauty in her landscapes that transcends their visual simplicity. Although they aren’t technologically impressive by mainstream standards, there’s something about the gestalt of image, sound, and movement that escapes the reach of screenshots—a sense of atmosphere far more polished and powerful than its graphics. It’s something that often works to her advantage; good horror frequently relies on the off-kilter and the unexpected for its thrills, something that can get lost as mainstream video games swell with multimillion-dollar budgets and grow increasingly glossy and risk-averse.

“In big-budget horror games where everything is beautiful and there are lots of lighting effects and detail—even though these games are ostensibly horrible, we can be comforted by the fact that they’re beautiful,” says Horrorshow. “But so many old horror games are really creepy to me because the character models would move in uncanny, unnatural ways because that was the technology of the time. On a really basic level, it’s unnerving to look at something that’s grainy and washed out and kind of broken and wrong. It’s an almost holistic horror.”

As the rare genre that welcomes the ugly and the broken, horror lends itself well to Horrorshow’s minimalist aesthetic—particularly psychological horror, where the scariest things are usually the ones you don’t show. (It’s a strong aesthetic choice on its own, but one that also happens to be attainable for developers on tight budgets) Grandmother, her only game that features a person, leads you into a house where an old woman sits moaning in a rocking chair, her face uncomfortably featureless. Elsewhere, you encounter walls that roil with reddish colors, and it’s hard to tell if they’re made of gore or just abstract textures. There’s a sort of lo-fi glitch horror at play, one that heightens the tension by forcing your mind to fill in the details.

The world of indie horror movies has produced some of the scariest work in recent memory with a similar less-is-more approach; few films have invigorated the genre in recent years like the low-budget productions It Follows and The Babadook, whose idiosyncratic visions would be unlikely to be funded as expensive mass-market productions—particularly The Babadook, which was directed by a woman and secured part of its budget through a Kickstarter campaign. (Horrorshow also relies on crowdfunding and direct distribution.)

Anatomy was partly inspired by ’90s indie horror hit The Blair Witch Project, a film that purported to be found footage of teens lost in the woods. Shot entirely on handheld cameras, it was grainy, raw, and terrifying largely because of the way it defied mainstream horror expectations and made the viewer feel viscerally close to something real and wrong. Horrorshow does something similar with Anatomy, not only by filtering the story through old camcorders and cassette players but by attacking your fundamental expectations of how a computer game is supposed to work. At one point, the game shuts itself down in what seems like a very abrupt ending, but don’t be fooled. Open the program again, and you’ll return to the house to find that things are slightly off—more disturbing and degraded, like a tape that’s been copied over and over.

The house of Anatomy is disturbing not only because it is a seemingly familiar space that grows increasingly sinister but because it attacks your ideas about how games work in ways that are equally unnerving. It wrests control away from you, tosses you out its creaky doors, and dares you to walk back in. The layout of the house is based loosely on the floor plan of Horrorshow’s childhood home, where the basement was similarly imbued with a sense of terrible importance.

“When I was about 5 or 6 my family moved into a house where the basement wasn’t finished,” she says. “It didn’t have carpet, you could see all the fiberglass insulation, all the walls were bare brick. It felt strange—like it didn’t belong with the rest of the house. I had this abject fascination with it. When I’d have trouble sleeping, sometimes I’d get out of bed and just stand at the top of the basement stairs and just stare down into it and think about it. It unsettled me, and I liked that.”

Playing Horrorshow’s games often feels like gazing into that basement, being drawn toward the threshold of something that frightens you for reasons you cannot explain. They are experiences where the place is the story, one we tell by exploring its strange pyramids and dark hallways—buildings that take the shape of the fears we cannot name. Perhaps that’s why it’s often difficult to tell when her games are over, or whether they ever truly finish at all.

“Locations don’t have endings,” says Horrorshow. “If you visit an archaeological site or a famous structure, it’s not like a story happens and ends neatly. You go in, you wander freely, you get a sense of the place, you discover. It ends when you feel you’ve had enough—when there’s nothing left to find.”