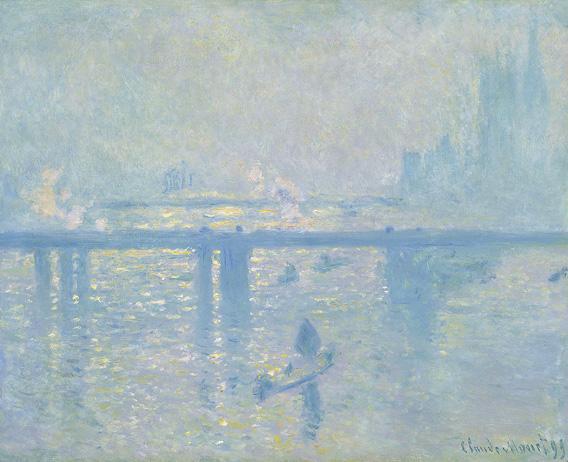

Thieves stole hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of paintings by Picasso, Monet, Gauguin, and Matisse from a museum in Rotterdam, the Netherlands on Tuesday morning. Since everyone knows the paintings are stolen, it’s impossible to sell them at auction. How do thieves profit from a high-profile art heist?

The black market. Most stolen art work goes underground. The thief sells his haul to an unscrupulous art dealer, who usually sells it on to a private collector who keeps it for a while. After several years and many subsequent underground transactions, relatively obscure pieces can be sold in the open, especially through small auction houses that don’t specialize in art. Even after a generation, however, it will be very difficult to bring a stolen Picasso or a Monet back to auction.

Thieves offer paintings by the masters at incredible discounts. According to Joshua Knelman’s book Hot Art: Chasing Thieves and Detectives Through the Secret World of Stolen Art, a stolen painting usually goes for around 10 percent of its legitimate auction value in the first sale between criminal and shady dealer. The price is low because both parties are at risk. The initial buyers usually know the works are stolen, especially since experienced black marketeers typically buy only from thieves they’re already familiar with. In subsequent sales, the price usually jumps substantially as the risk of punishment drops. In the United States, for example, buyers can be prosecuted under the National Stolen Property Act only if the government can prove that they knew the item was stolen. Once a painting changes hands two or three times, buyers can plausibly (and sometimes honestly) claim that they thought it was legitimate.

The London-based Art Loss Register allows owners and dealers to register their works of art, and urges buyers and sellers to conduct a title search before agreeing to a transaction. Many dealers, however, have resisted the process. Some don’t want to pay the $95 search fee, which is a pittance compared to the cost of a Picasso, but a non-negligible amount in smaller transactions. Others don’t like regulation and public scrutiny of their transactions.

Thieves who don’t know a black-market dealer have a couple of other options. They can try to sell the work as a knock-off of the original at an enormous discount. They can, alternatively, hold the painting for ransom from the rightful owner. In 1986, for example, an Irish criminal group stole paintings by Vermeer, Rubens, Gainsborough, and Goya owned by the National Gallery of Ireland and tried to extract a ransom from the government. The thieves made the mistake of threatening to kill an art expert who they asked to authenticate the paintings. The terrified dealer called Scotland Yard.

Got a question about today’s news? Ask the Explainer.