An unidentified buyer purchased Edvard Munch’s The Scream for nearly $120 million at auction on Wednesday. Despite the phenomenal popularity of The Scream, it’s likely that few people outside of Norway could name another Munch painting. Are there one-hit wonders in the world of fine art?

Yes. Plenty of painters have managed to capture the public’s attention with a single work of genius, while their other work remains relatively unknown. The best known to Americans is Grant Wood, who painted American Gothic, but Théodore Géricault (The Raft of the Medusa) and Antoine-Jean Gros (Bonaparte Visiting the Plague Victims of Jaffa) are also classic examples. These artists produced plenty of other work before and after creating their masterpieces, but none earned them much public notice or critical acclaim.

University of Chicago economist David Galenson has compiled a list of one-hit-wonder artists in recent history, based on the number of mentions their masterpieces have received in scholarly literature, compared to mentions of their lesser works. According to this approach, the sculptor and landscape artist Maya Lin might be the classic one-hit wonder. When she designed the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. while still a college student in 1981, her work was absolutely revolutionary. Before Lin, war memorials almost always featured statues of soldiers. (Think of the Iwo Jima Memorial.) Today, they almost never do. And yet, Maya Lin hasn’t produced anything else that’s been deemed worthy of much talk in academic circles.

Galenson explains the phenomenon by breaking artists into two categories. Experimentalists refine and improve their ideas over the course of their careers, producing their best work later in life. Cezanne’s later paintings, for example, sell for significantly more than his early works. Conceptual artists, in contrast, are revolutionaries—they turn heads by taking a completely new approach. Picasso was conceptual. Even though he worked into his 90s, he did his most interesting work in his 20s. Picasso wasn’t a one-hit wonder, of course, but many conceptual artists tend to fade away after unveiling their big, revolutionary idea. What started as an exciting, new approach eventually becomes commonplace, and few conceptualists have more than one revolutionary idea to share.

It might be unfair to categorize Edvard Munch as a one-hit wonder. His 1894 painting Vampire sold for $38 million in 2008, and plenty of art critics are interested in his lesser-known work. Still, he fits rather well into the conceptualist-revolutionary category. With his manic line patterns and color palettes, Munch introduced a new aesthetic to painting in the 1890s, and critics didn’t know how to categorize much of his early work. (A Frankfurt newspaper wrote that an 1892 Munch exhibition “put art in mortal danger,” and an association of German artists voted to shutter it after only a few days.) But Munch lost something as he aged. His 20th-century paintings show technical mastery, but most critics find they lack the emotional impact of his Frieze of Life series, of which The Scream was a part. Some historians attribute the blandness of Munch’s later paintings to his improved mental health, but it’s possible that he simply ran out of ideas.

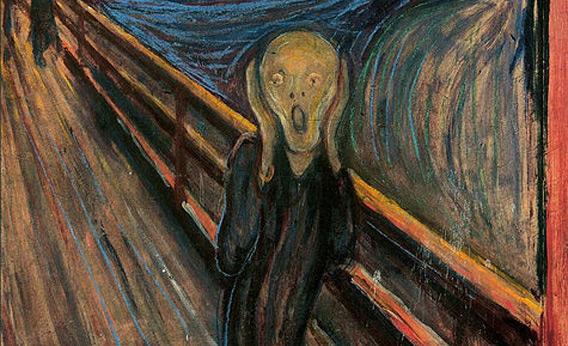

Bonus Explainer: What’s so great about The Scream, anyway? Like later Expressionist works, it filters sensory perception through the human psyche. Munch’s swirls capture the chaotic, vibrating pulses that a particular Oslo sunset had produced in his mind. The lines seem to race away from the painted figure, providing a feeling of vertiginous isolation. The face is devoid of recognizable personal traits—it is “sexless, twisted, [and] fetal-faced,” one journalist wrote—as though terror has stripped its identity.

Why did The Scream, and not other works done in the same style, become the most famous painting since the Mona Lisa? The most widely accepted explanation is that it continues to terrify us. Munch noted that he’d created an image for a godless age, as people struggled to understand their place in a world without divine purpose. (That’s one of the reasons the painting shocked 19th-century audiences.) After a century of mechanization and generally advancing secularism, The Scream continues to resonate because the inner turmoil it depicts remains part of the human condition. By this theory, the endless stream of gag gifts and memorabilia that feature the painting, including greeting cards, blow-up dolls and Whoopee cushions, represent an attempt to soften The Scream’s overwhelming psychological impact.

Got a question about today’s news? Ask the Explainer.

Explainer thanks David W. Galenson of the University of Chicago, author of Old Masters and Young Geniuses: The Two Life Cycles of Artistic Creativity, and Elizabeth Prelinger of Georgetown University, author of Edvard Munch: Master Prints.