Free to be … who? All the musicians, artists, feminists, and other figures mentioned in this series.

Want to listen to Free To Be … You and Me? Here’s a Spotify playlist.

And lo, the word went out to New York’s songwriters and children’s book authors and frustrated Broadway bards and William Morris clients in the spring of 1972: Marlo Thomas, the star of That Girl, is putting together a children’s album, and she needs material. Sexist pigs need not apply.

To get things rolling, Thomas held a series of late-night brainstorming sessions that spring at her East 71st Street apartment: wine, pizza, and consciousness-raising. Carole Hart, the young producer Thomas had chosen for the album, and her husband, Bruce, a lyricist, came. So did Letty Cottin Pogrebin, the editor at the brand-new Ms. magazine who was serving as the project’s “feminist Jiminy Cricket,” making sure the album stuck to core principles of the movement. Mary Rodgers, the songwriter and children’s book author (and daughter of composer Richard Rodgers), was there, sent by her legendary editor at Harper & Row, Ursula Nordstrom. From Thomas’ circle of friends there was boyfriend Herb Gardner, Shel Silverstein, the screenwriter and playwright Peter Stone, and Gardner’s good pal Paddy Chayefsky. Thomas posed a simple question to them all: What lessons or stories do you feel were missing from your childhood?

Courtesy Marlo Thomas.

From those conversations, many of the album’s themes emerged. Thomas remembers Gardner saying, “I wish that somebody had told me that it was all right to cry without being called a sissy.” Thomas herself wished for a story where the princess wasn’t blond and she didn’t marry a prince at the end.

Together, Thomas and Pogrebin and the rest of the informal creative team honed in on four overarching ideas that the album should convey. As Thomas later described them to the New York Times:

- “The celebration of the self, the idea that a child should feel, ‘It’s terrific to be me; I’m unique.’ ”

- “What parents can be.”

- “Children should be themselves in what they do and what they feel.”

- “Boys and girls should play together.”

“I wanted the Free To Be project to be a cushion underneath children,” Thomas says now. “Something that would be a springboard, to say, ‘Yes, you can. You can do it.’”

Courtesy Stephen Lawrence.

So now they had a list of ideas. All they had to do was write an entire album and hire a cast of performers famous enough to sell it. Not only that, but they had to get the backing of a record company. Thomas’ agent at William Morris offered the project to several without success. Eventually the album ended up at Bell Records, a brand-new label under the Columbia umbrella. Bell paid an advance of $15,000 to the Ms. Foundation for Women, a nonprofit formed by Thomas and Gloria Steinem as a repository for profits from the record. Not that they thought there would be any; a Bell exec told Thomas they expected the album to sell no more than 15,000 copies. That was still better than the response Carole Hart remembers from a different music executive: “What would I want with a record produced by a bunch of dykes?”

Carole asked her husband, Bruce, to write a theme song for the whole record to give the project a name. “Bruce came up with the phrase Free To Be You and Me Jamboree,” Carole says. “You can’t stop a lyricist from liking those triple rhymes.” But Carole convinced Bruce, who died in 2006, to drop the “Jamboree” and presented the title to Thomas, who thought it sounded bland. Bruce and his frequent collaborator Stephen Lawrence wrote a song to go with the title anyway: an folk-pop anthem inspired by “This Land Is Your Land.” They just had to sell Thomas on it.

“I hadn’t worked with Marlo, and she was very strong and had very specific tastes, and I wanted to please her,” Lawrence says. “And I wanted to get it out of the way so I didn’t have to think about it because the stakes were so high.”

Thomas and Carole Hart and Pogrebin went to Lawrence’s squalid bachelor pad on West 56th to hear the writers perform the song on his piano. “I didn’t like to wash dishes,” Lawrence recalls, “so to keep the roaches at bay, I would fill the sink with soapy water and put dirty dishes in there, sometimes for a long time.” Thomas asked if Lawrence could get her a glass of water, and he replied, “I don’t know.” But the jaunty song was a hit, and the album had a title.

Photo by Richard Blinkoff.

Thomas reached out to other friends. She and Hart asked Shel Silverstein for something funny, edgy, not at all sentimental. He turned in a tart song, “Helping,” and a scathing poem, “Ladies First,” which Mary Rodgers adapted for performance. Peter Stone asked his friend Carl Reiner to write a variation on his popular “2000 Year Old Man” sketches, a two-hander in which two babies speculate on their own genders. Also in their circle was the writer Dan Greenburg; he was about to leave for Martha’s Vineyard to shoot his movie I Could Never Have Sex With Any Man Who Has so Little Regard For My Husband, but Thomas and Hart still asked him to contribute. He wrote two short, funny poems by hand one afternoon while on break from shooting and sent them in.

Other assignments came about through more traditional industry channels. Carol Hall got a phone call from her agent, Scott Shukat. The Texas-born singer-songwriter’s debut album had not sold particularly well, and she was still several years away from writing The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas, so she threw herself into her first Free To Be gig: Write a song about how mommies and daddies are people, too. She’d been tipped that Thomas was going to sing some of the songs on the album and that she was nervous enough about her voice to have hired a vocal coach. Hall wrote a simple, hummable melody with lines she thought might get Thomas’ attention, as when she noted that some daddies are “funny joke tellers”—like Thomas’ own father, comedian Danny Thomas.

Thomas and Hart were on the hunt for a musical director for the album—someone who could arrange, conduct, and control the way the songs sounded. As part of his audition for the role, Lawrence, later an Emmy-winning composer for Sesame Street, met Thomas’ voice coach, Colin Romoff. “He had to bless it every time she opened her mouth in song,” Lawrence remembers. “She relied on him very heavily.” Lawrence and Romoff discussed Thomas’ range and experience as a singer (limited and limited), and began preparing her for the songs she would perform on the album.

As summer arrived, so did the songs and sketches: on paper, on audiotape, performed in studios and living rooms for the three women. Abby Pogrebin remembers her mom, Letty, bringing demo tapes to their summer rental on Fire Island, N.Y., to test them out on the kids. “I knew we had something amazing,” Letty says, “because within three hearings they were singing along.”

Mary Rodgers recruited her neighbor and friend, Fiddler on the Roof lyricist Sheldon Harnick, to collaborate with her on “William’s Doll,” based on the one book suggested by children’s publisher Ursula Nordstrom that Thomas liked. (It was written by Charlotte Zolotow, Nordstrom’s protégée.) Harnick, on the advice of all the feminists he was meeting through Free To Be, read Sisterhood Is Powerful, and one chapter on the politics of cleaning inspired him to write a poem about how no one likes housework; Thomas added it to the roster. (A decision the team would later regret.) Hart’s literary agent suggested she contact children’s author Betty Miles; Hart assigned Miles an adaptation of the Greek myth of Atalanta, a princess racing against young Melanion, who desires her hand in marriage. Miles rewrote the tale’s original ending—in which Aphrodite helps Melanion win the race and get the girl—to reflect a more liberated time.

For Carol Hall’s second assignment, “It’s All Right To Cry,” she went to the Little Red Schoolhouse in downtown Manhattan and quizzed her son’s classmates on their feelings about crying. “Crying gets the sad out of you,” one child suggested. “It’s like raindrops from your eyes,” said another. Chuckles Hall today: “Poor little darlings, their names are not on the copyright. Thank you, children!” Once again hoping Thomas might sing the song, Hall tailored it to her. “How am I going to say this so that in print it sounds graceful?” Hall muses now. “Marlo is a wonderful, wonderful performer, but she is such a perfectionist that I knew that singing was not something she was accustomed to doing that much. So because I thought that Marlo might sing it, I wanted to aim it to her, melodically, so I made it very, very simple.”

The song was accepted, and then, Hall says, “I was about to pop to get a third thing on the record, because nobody else had three.” (She was getting updates from her agent, Shukat.) She composed a song for Kris Kristofferson, who’d written the liner notes for her first album and sent it to him without telling anyone. “Oooh, Carole Hart was mad at me because I sent it to Kris directly.” Kristofferson turned the song down; he would later appear on the Free To Be TV special. And Hall did eventually land that third song, about friendship between boys and girls, “Glad to Have a Friend Like You,” which wound up closing the album.

Friendships or no, this was still business. The project’s attorney, Robert Levine, husband of Ms. managing editor Suzanne Braun Levine, drew up deals for all the participants: Writers assigned their copyright to the Ms. Foundation for a period of five years, after which they could request reversion. The foundation would pay mechanical royalties—royalties due to composers—from dollar one and record royalties to performers after Bell Records recouped its advance. “We all felt the contributors should be paid for what they did,” Levine says. “I mean, Marlo never takes any money for anything, and a great many of the performers waived their financial interests for the benefit of the foundation. But we set up an accounting system to be sure that people were compensated.” And people were: Dan Greenburg marvels today that while the movie he went off to film in Martha’s Vineyard—the one he thought would make his career—was a total flop, the two poems he dashed off one afternoon on set have resulted in steady royalty checks every year since.

* * *

Pretty much everyone I spoke to credits Thomas with the project’s ultimate creative and financial success. She was a taskmaster, but an enthusiastic one. Even 40 years later, I kept hearing the phrase “force of nature” spoken both admiringly and anxiously about her. Pogrebin, asked what Thomas was like at the time, gives a straightforward answer:

She is very strong, very opinionated, and tireless. People knew exactly what she wanted, and they gave it to her, and they knew when they didn’t. She was very direct. She was a real executive. She was comfortable in the authority role. And she had the last word on everything. She had a vision. You didn’t have to mess around. Her enthusiasm is infectious. She’s funny. I remember her with no makeup and exhausted after some of the recording sessions. She looked about as washed out as a movie star could possibly look, but she had this luminous look in her eye like, We got it. We did it. It’s right, it’s perfect, it’s great. And that’s what you want to see in a creative person.

Courtesy CBS Television.

In early summer, that creative energy was put to use assembling the cast of actors and singers who would perform Free To Be. Thomas, the daughter of a successful comedian and satellite Rat Packer, had grown up in Hollywood, and in 1972 she reached out to every famous person she knew, it seemed. And pretty much everyone said yes. “Marlo … is very persuasive,” laughs Levine.(Carol Burnett, who was originally meant to perform the poem “Housework,” had a scheduling conflict. The only person anyone can remember flat turning the project down was Alan Arkin, who was, according to Mary Rodgers, “very grumpy and totally uninterested.”)

One of the first calls Thomas made was to her friend Alan Alda, whom she’d met on the set of the 1970 drama Jenny. Alda agreed to perform on the album and also to direct the storytelling portions—the poems and short radio plays that made up half the record. Alda, Thomas, and Hart decided that those sketches, wherever possible, should use sound effects and Story Theatre-style acting techniques to make them come alive. Thomas still remembers running in place while recording the race sequence of “Atalanta.”

The sketches were recorded at the grand MediaSound studio on West 57th Street over the course of a few days. Billy De Wolfe, Thomas’s co-star on That Girl, lent his distinctive voice to several roles on the record, including the dandyish principal who plays the flute for Dudley Pippin. (Dudley Pippin himself was voiced by “Bobby Morse,” better known now as cranky senior partner Bertram Cooper on Mad Men.) Some of the sessions were quite impromptu: Dick Cavett remembers getting a call from Thomas in the morning—“I had a show to tape that day, and I thought, well, God, I can’t really do it, but I like her, and she does good stuff, and also I was very familiar with her face because on my daytime show the promo for That Girl ran at least 10 times during each show”—and walking the few blocks from his office to MediaSound to record that afternoon.

Mel Brooks’ session was more eventful. Thomas had written to him that the album “would benefit the Ms. Foundation,” and when he came in the morning of his recording, he told her that he thought the material Reiner and Stone had written was funny but that he didn’t know what it had to do with multiple sclerosis. Once set straight about the MS in question, Brooks joined Thomas in the recording booth, where they would both play babies for the album’s first sketch, “Boy Meets Girl.”

“When I directed,” Alda recalls, “I would be meticulous and relentless. I would do a lot of takes. But Mel is not a guy who’s used to doing a lot of takes. He’s not used to taking direction from anybody—you know, he gives direction.” Alda didn’t love the first few takes of “Boy Meets Girl”; in the end it took, Alda remembers, 10 or 15 tries, with Brooks improvising madly all along the way. Rodgers was there that day to record “Ladies First,” and she still remembers standing in the control room laughing harder with each take. “Mel was generous,” Alda allows, “and he let me egg him on.”

Lawrence, the project’s musical director, assembled musicians and began recording the backing tracks at Phil Ramone’s A&R Recordings, on the corner of 48th Street and Sixth Avenue. He wasn’t much of a conductor, he admits. (But: “I never ever turned down a job because I didn’t know how to do it.”) While recording the tricky “William’s Doll” with its multiple tempo changes, Lawrence saw Sheldon Harnick, the song’s lyricist, standing in the control room and invited him in. “Just stand next to me,” Lawrence said, “and tell me how you want it as I’m conducting it.”

Diana Ross came down to the city from her house in Connecticut and nailed “When We Grow Up” in one take. (For the 1974 TV special, the song would be rerecorded by Roberta Flack and a 15-year-old Michael Jackson. More than one person remarked to me how ghoulish and sad it was to see a dark-skinned, fresh-faced Jackson sing, “We don’t have to change at all.”)

Courtesy of Kitschy Living.

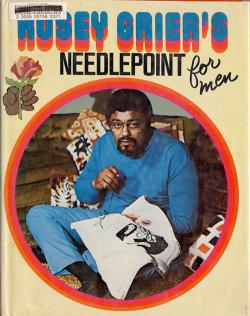

To rope in other singers, Thomas, Lawrence, and Hart went on the road. Former NFL star Rosey Grier was performing nightly at the Playboy Club in Chicago, so off to Chicago the trio went to record Grier singing “It’s All Right To Cry.” Grier asked Lawrence to give the song a little bit more of a beat, so he added drums to the acoustic guitar in the mix; Thomas wanted Grier to speak-sing the lyrics, but Grier wanted to croon. He prided himself on his sensitive nature. (The next year, he would release a book called Rosey Grier’s Needlepoint for Men.) Even today, he gets upset when discussing the song. “What right does someone have to tell a little baby boy not to cry because he’s a grown man?” he asks me. “The hurt is just as bad, the pain is just as bad, there’s no feeling different than the girls. So why should he have to hold it in and be sniffing and trying not to cry? Because they’re going to make fun of him? Forget all that, man. If you want to cry, cry.” During the recording, he ad-libbed his final line: “It’s all right to cry, little boy. I know some big boys who cry, too.” “Oh,” Hart remembers, “after he finished it I just jumped up and gave him a huge hug and said, ‘Thank you! Thank you!’ ”

The team flew to Los Angeles to record Tom Smothers for 48 seconds. Lawrence carried the instrumental recordings on big reel-to-reel tapes in cardboard boxes on his lap on the way out, then carried the vocal tapes in cardboard boxes on his lap on the way back. In Las Vegas, they recorded Harry Belafonte singing his part on “Parents Are People.” Thomas had already recorded her side of the song at A&R in a key she felt comfortable in, but “When it was all over,” Hart remembers, “we played it back to him, and he didn’t like the way he sounded because it was in the wrong key. And he said, ‘You can’t use it.’ ” Thomas tried to convince Belafonte to change his mind; Hart followed up. By then it was days before the final mixes were due. “He wouldn’t budge,” Hart says. “I was at the end of my wits. And I just started sobbing. And that got to him!” She laughs. “That was a feminine trick, I guess. I didn’t mean it as a trick. I was just so frustrated.” Belafonte relented, and the track went on the record.

Mastering and sequencing went right up until the very last day—Hart recalls pulling an all-nighter before the listening party at Ms. headquarters on 41st Street and Lexington Avenue the next day. The evening of the party, Hart and her husband, Bruce, brought the tapes to the magazine’s office. Gloria Steinem was there, and Letty Cottin Pogrebin, and the rest of the Ms. editorial team. Thomas and Alda and a number of the singers and writers were there. Carol Hall came and sat like “a mouse in the corner”; no one knew who she was since she’d turned in every song through her agent. “Listening to the record, though, with all these people whom I didn’t know all around, and I was thinking, ‘I wrote three of those songs.’ So it was kind of like a very nice secret I had.”

Carole Hart was too anxious to stay in the room while the master recording played. She sat in the hall with the door open and listened to the big laughs at Thomas and Mel Brooks as babies, the applause at the end of some of the songs, the sounds of the nine months she’d spent working day and night on a project that was about to head out into the world. “I calmed down a little bit,” she recalls, “but I still didn’t go in.” When the record ended, Hart exhaled and smiled. The first two women to walk out the door chattered as they strode past Hart. “Well you know,” one said, “it had a very heterosexual bias.”

Next: Did the album change anyhing? Previously: How did the album begin?