For the past several decades, British sociologist and preeminent humor scholar Christie Davies has been collecting examples of an odd phenomenon: Nearly every culture has its own version of the Polish joke. That is, every country likes to make fun of people who’ve been labeled as simpletons and, often, outsiders.

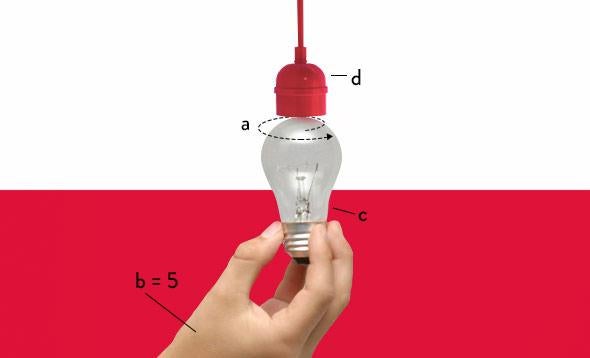

In this country, we mock the poor, put-upon Poles: “How many Polish guys does it take to screw in a light bulb? Five: One to hold the bulb and four to turn the chair.” (Polish-Americans became the butt of jokes after millions fled persecution in their own country in the 18th and 19th centuries, often taking up menial jobs in their new American home.) But that’s just one example of what Davies calls the “stupidity joke.” People all over the world and throughout history have differentiated themselves from those they see as inferior and foreign by making fun of them. Take the oldest-known joke book in the world: Philogelos, Greek for “The Laughter Lover,” compiled from several manuscripts dating from the 11th to 15th centuries but believed to have been penned in the 4th century A.D. by the otherwise unknown scribes Hierokles and Philagrios. Of the 265 jokes in the book, nearly a quarter concern people from cities renowned for their idiocy, like Cyme in modern-day Turkey and Abdera in Thrace. Later, in medieval England, people cracked jokes about the dunces who lived in the village of Gotham. (New York’s nickname, “Gotham,” doesn’t sound so impressive when you learn that author Washington Irving coined it to suggest the place was a city of fools.)

The phenomenon is truly global. According to Davies’ research, Uzbeks get made fun of in Tajikistan while in France, it’s the French-speaking Swiss. Israelis rib Kurdish Jews; Finns knock the Karelians, an ethnic group residing in northwestern Russia and eastern Finland. The Irish, it turns out, have a particularly bad lot. Dumb-Irish jokes are equally common in England, Wales, Scotland, and Australia. Although it could be worse: If you happen to be an Irishman from County Kerry, you even get made fun of by your fellow Irishmen as well. The model even extends to the work world: Orthopedic surgery might be a highly competitive field, but other surgeons deride such rough-and-tumble musculoskeletal work as inferior. (“What’s the difference between an orthopedic surgeon and a carpenter? The carpenter knows more than one antibiotic.”)

“Nearly every country has stupidity jokes,” Davies told us when we visited him in Reading, England. The fact that he’s uncovered a nearly universal kind of joke is all the more incredible considering the vast majority of humor is the opposite of universal. There’s a reason that action films are far more likely to be global blockbusters than comedies. Humor is incredibly subjective—what you find funny varies immensely by upbringing, age, gender, political affiliation, and a host of other factors.

Some cultures have diverse brands of comedy while other societies’ humor is remarkably uniform. When we traveled to Japan, immersing ourselves in sadistic game shows, ribald karaoke excursions, and the (mandatory!) comedy training schools for aspiring comedians, we hardly understood any of the jokes. That’s because most of them didn’t bother with set-ups at all. As a member of the Japanese Humor and Laughter Society explained to us, Japan is a high-context society: It is so homogenous, jokesters don’t need to bother with explanations or detailed backstories. They can get right to the punch line. One common joke, about an Olympic gymnast whose leotard was hiked embarrassingly high during a performance, has apparently become so familiar that even the punch line isn’t necessary. All you have to do is gesture to your upper thigh.

Each country’s particular brand of comedy is so intertwined with its social and cultural baggage, in fact, that enterprising academics are using the birth and spread of specific kinds of jokes to uncover hidden quirks of various societies’ cultural DNA. Davies has proven especially proficient at this. He traced the spread of dumb-blonde jokes, for example, from their origins in the United States in the mid-20th century to Croatia, France, Germany, Hungary, Poland, and Brazil, deducing the zingers emerged as women shook up gender roles by entering high-skilled professions. When the so-called Great American Lawyer Joke Cycle of the 1980s didn’t spread anywhere beyond the United States, Davies concluded the jokes were a uniquely American phenomenon because no other country is so rooted in the sanctity of law—and in no other country are those who practice it so reviled.

Next up: Can jokes lead to political change? The rise of laughtivism.

This series is adapted from The Humor Code: A Global Search for What Makes Things Funny.