This article is part of Postcards from Camp, a multi-part series on the nature and contemporary relevance of camp sensibility. Read all of the entries here.

Kylie Minogue, ever the incisive chanteuse, puts her manicured finger directly on a big part of the reason camp can seem so confusing: “How do you describe a feeling? I’ve only ever dreamt of this.”

So much writing about camp has had a certain dreamy quality, both in its imagistic richness and tendency to trail off into incoherence as the subject slips out of focus. We have been told that this is due to the difficulty of defining camp or at least of taxonomizing it. But perhaps it’s not camp that’s causing the trouble, but rather our rude way of greeting it. Instead of screaming “WHAT ARE YOU?!?!” over and over again at camp, maybe we should politely ask how it’s feeling today.

Of course, as Kylie points out, describing a feeling is hard. They are accidental, visceral, intoxicating things—notoriously difficult to justify to outsiders. But we must try, because understanding camp’s fundamental status as a kind of pleasure—the pleasure of the nuance—is central to freeing it from the perishable associations that have plagued it for a half-century or more. Luckily, Wayne Koestenbaum has given us a firm place to start in his meditation on the peculiar infatuation gays have historically had with opera:

“When we experience the camp rush, the delight, the savor, we are making a private airlift of lost cultural matter, fragments held hostage by everyone else’s indifference. No one else lived for this gesture, this pattern, this figure, before: only I know that it is sublime.”

Let’s put on our close-reading glasses for just a moment (the ones with the rhinestone frames and the beaded chain). In the first clause, Koestenbaum helpfully breaks down the three stages of the camp experience: the rush, the delight, and the savor.

The rush is essentially preverbal, or perhaps beyond language entirely, which is why it is usually expressed in a giddy squeal or some other potentially humiliating spasm—for me, most often an extreme widening of the eyes. It is a feeling not unlike the shock of unexpectedly encountering your best friend on a crowded street in a foreign county, only without any disorientation; since camping is an almost instinctual practice of scanning mundane reality for little miracles, encountering a “glitch in the Matrix” isn’t confusing, just arousing. In other words, the rush is recognition before cognition, affiliation without identification, id exploding from your psyche like the little mouth in Alien. The rush, as you might imagine, has the propensity to draw stares.

But just as quickly as that aesthetic erection takes place, the delight arrives with the ego in tow to impose a little order. It’s in this stage that you realize you’re having a camp moment—to take pleasure in that fact—and begin to consciously process whatever shimmer has instinctively tweaked you out. You begin to find words and initial associations, perhaps precedents, to contextualize your reaction.

Still, even the most brazen camper senses that this kind of joy is weird, perhaps even actively anti-social. Like the sudden surge of guilt that can sometimes follow sex, there is often a moment in the camp progression where the superego reminds you that you’re probably doing something bad. Thankfully, however, the savor sends it packing. The savor is all about complicity, the sly sense of satisfaction that comes when you remember that you are special for having camped, that not everyone is blessed with such rapture, that you are part of a small but illustrious family of those who “get it.” To be clear, this is not to say that all campers will alight upon the same nuances (though it can happen). Rather, what the savor acknowledges and celebrates is the shared sense that campers are looking at the world from an askew point of view.

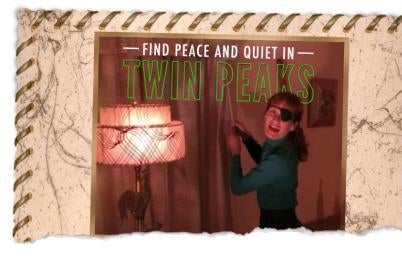

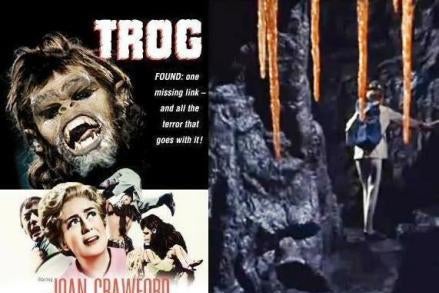

While the savor may come off as exclusive and self-aggrandizing, Koestenbaum’s rescue metaphor demonstrates the compassion at the heart of camp. The camp warrior is constantly running missions into enemy territory to “rescue” this or that prisoner (say, Joan Crawford’s cream pantsuit in Trog or a curtain rod from Twin Peaks) from malicious obscurity.

Camp is the only thing between Joan’s pantsuit and oblivion.

Trog still courtesy of Warner Bros.

To the camp-attuned eye, these “fragments” clearly deserve the utmost reverence and appreciation—lavish retrospectives and month-long festivals, really—even though society at large couldn’t care less. Deep down, camp wants to conserve.

Camp slows reality down long enough for you to consider its most minor components, long enough for you to collect little darlings for your private cabinet of curiosities. For its practitioners, camp is a retreat, a respite from overbearing ideologies, preapproved narratives, and, above all, the fascism of usefulness. Instead, it offers a rare quiet space where one can freely meditate on a “gesture,” a “pattern,” or a “figure.” It’s a twilight garden where, while chasing one of those fanciful fireflies, you may indeed just stumble upon the sublime—especially if you’re wearing heels.