This article is part of Postcards from Camp, a multi-part series on the nature and contemporary relevance of camp sensibility. Read all of the entries here.

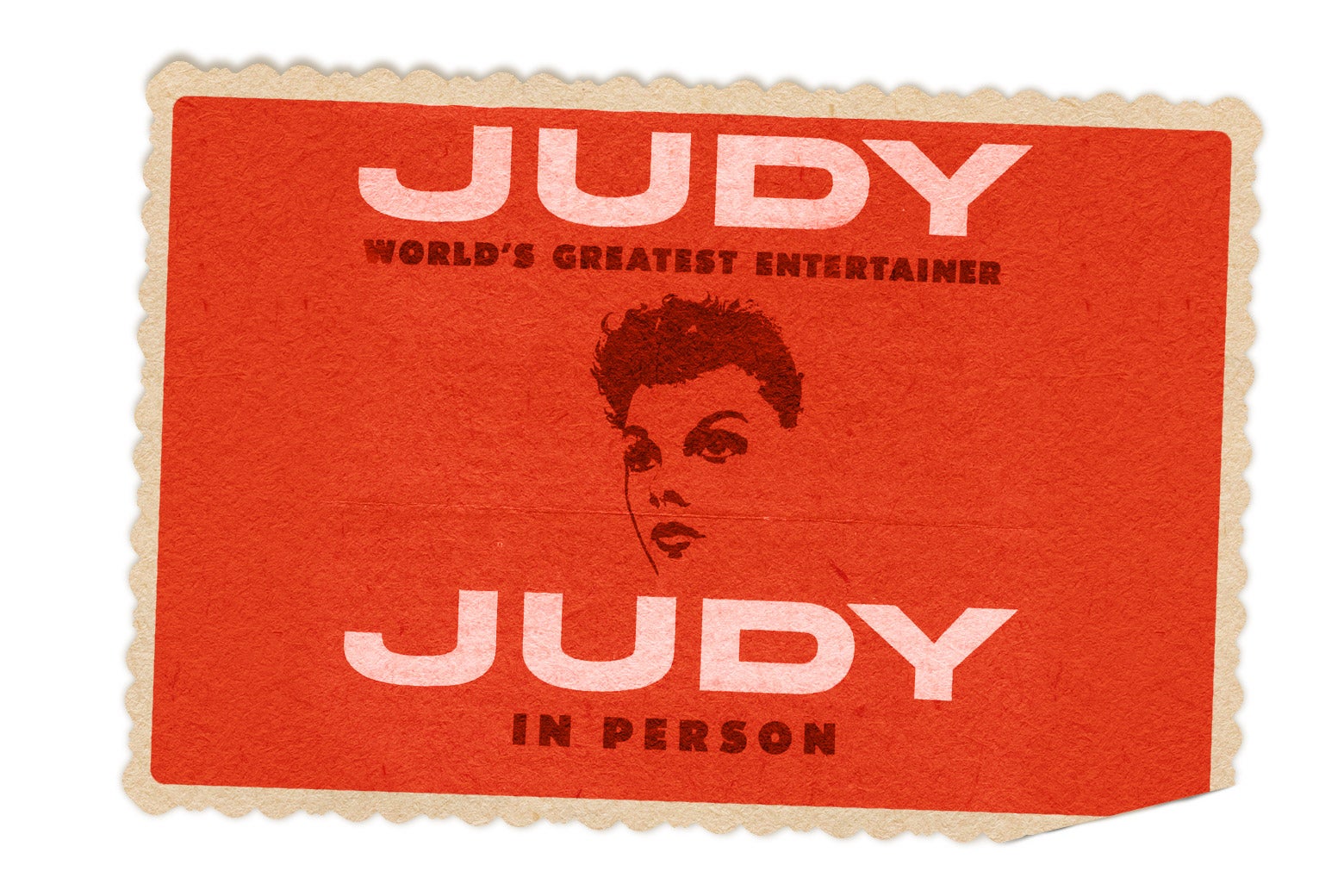

June 27, 1969. The Upper East Side of Manhattan. After having her makeup done by the same artist who had painted her in The Wizard of Oz, camp icon Judy Garland—that great, tragic, consummate performer—greeted her admirers for a final show in a white, glass-topped coffin. Judy had overdosed on barbiturates. Liza insisted that no one wear black. According to Charles Kaiser’s account in The Gay Metropolis, “more than twenty-thousand fans waited in the fierce summer heat to pay their last respects.” Many of them were confirmed bachelors and bachelorettes, and some number of those had lived for Judy eight years earlier during her storied performance in Carnegie Hall. Now that she was dead, they lived for her even more.

A few probably ended up back downtown that night at the Stonewall Inn, a dingy, mob-run pervert bar in the West Village. While crammed into the pub, some of those men and women likely got riled up, filling themselves with liquor and leaking laughter and tears while reliving their favorite nuances from Judy’s appearances and songs. Off-key strains of “Somewhere over the Rainbow” may well have been heard by vagrants in the little trash-strewn park across the street.

Later, when a band of unassuming cops tried to raid the bar and arrest a handful of patrons just after midnight, some of those drunk, riled-up men and women and men who dressed like women and women who dressed like men fought back. “This,” as Kaiser so perfectly puts it, “had never happened before.”

No one knows for sure what “started” the Stonewall Rebellion of 1969, but I choose to believe it was Judy. I choose to believe it was camp.

It’s come time to talk about the massive rainbow elephant that has been awkwardly mincing across this series since the beginning—the intimate relationship between gays and camp. Which is to say, we must finally deal with the question most crucial to camp’s continued relevance: Who, ultimately, is camp for?

Sontag called gays the “vanguard” and “most articulate audience” of camp. As we explored earlier, she’s mostly talking about the limited style of campiness, but her designations are not totally inaccurate. Gays, especially of the male variety, have certainly thought about camp more deeply and practiced it more broadly throughout the decades than any other group. But the usefulness of this queer commitment to camp has been poorly understood. The most commonly held notion is that camp was both a secret, possibly subversive subcultural language and, a little later, a means affording gays a method of societal integration via a kind of comic minstrelsy for straights. Sontag calls this latter, Liberace-esque function “propagandistic,” in that campiness, as a “solvent of morality,” may work to convince homophobic straights that gays aren’t so objectionable—after all, we’re so funny!

Of course, that only works if the straights in question get the message. As noted neo-con Midge Decter revealed in an arrestingly prejudiced and yet entirely campable 1980 Commentary essay, at least some outsiders viewed campy style as “a brilliant expression of homosexual aggression against the heterosexual world … serving the purpose of domination by ridicule.” What a wonderfully paranoid fantasy! Despite the seepage of a mostly rote strain of campiness into popular culture in the past few decades, I see no evidence that it has allowed gays to “dominate” much of anything. But true camp has helped us out, and not merely as a source of catty, countercultural fun.

Two photographs rest on my credenza. The photos are both of dead men, yet the magnetic field emanating from their uneasy juxtaposition could not be more alive. Paul Newman—young, a Navy-man—smirks through full, just-parted lips, hints at summer heat with the languid gleam in his heavy, puppy-dog eyes. Oscar Wilde, meanwhile, appears both unavoidably foppish and studiedly aggressive, his delicate hand propping up his soft, elegant features while his legs spread wide enough to telegraph virility, or, at least, to accommodate a swag stick. Newman, the Platonic form of effortless masculinity, of manly beauty, just is. Wilde, meanwhile, strikes a pose, every detail just so.

Gay scholar David Halperin would recognize the logic behind my couple of portraits. In my pairing, I’ve captured what he identifies as a tension at the heart of gay male identity: The Beauty and The Camp. Halperin teases a great deal of insight about the gay male condition from this dichotomy in his book, but for our purposes, one point will suffice. If The Beauty is essentially lust—for attractive men, to be sure, but really for an ideal of tough, American masculinity—then The Camp is the balance to all that, the yin to The Beauty’s yang. The allure of masculinity, and with it the ability to pass, to conform, to go unmarked, is powerful in gay life, particularly because those who by nature or effort have achieved some measure of it are the most palatable to mainstream society. For many of us, however, disappearing into normalcy isn’t necessarily desirable. So how to resist? Camp sees the power that The Beauty holds over gay men and mocks it, breaks it down into the tiny, intensely studied nuances (postures, hairlines, speech patterns, gaits) that are necessary to form the illusion of masculine effortlessness. I may want Newman, but I need Wilde. I need him to be there beside The Beauty, outplaying the siren call of masculinity by studying it, rehearsing it, doing it better, doing it too well, drawing attention to the doing; in a word, camping it.

As we explored in the previous post, camp allows us to see the paradigms in operation all around us and recognize them for the arbitrary and possibly undesirable doxa that they are. But that power of critique is also the thing that makes true camp ultimately incompatible with any notion of normality, for normality, like masculinity, is too dependent on going unquestioned to bear camp’s dissecting gaze. In a moment when the thrust of the gay civil rights movement is directed toward penetrating as quickly as possible into mainstream society, camp is a massive cock block. Which, in the final analysis, is the reason many critics, gay and straight alike, are so eager to declare camp “dead.” Maybe ol’ Midge had it half-right after all: Camp is not a plot against heterosexuals, but it is definitely a threat to the “normal,” new or otherwise.

So, with all that said, who is camp for? Maybe it’s not just for gays anymore (if it ever was), at least not as a birthright. You can’t really claim ownership of something that so many of your supposed co-owners want to toss out. But as disappointing as that trend is, perhaps there’s a silver lining: As more and more gays fill their datebooks with commoner pleasures, camp’s calendar is increasingly open. Camp started a revolution for a group of people who have (or are sincerely trying to) leave it behind. That’s their loss. In the finale to this series, we’ll daydream a bit on how we holdouts—gay, straight, and otherwise—might make use of it going forward.