This article is part of Postcards from Camp, a multi-part series on the nature and contemporary relevance of camp sensibility. Read all of the entries here.

It’s one of the great accidents of intellectual history that Susan Sontag became known as the “philosopher” of camp. While she was responsible, of course, for elevating the concept to eye-level for the (straight) chattering class of the United States, her famous essay only provides a handful of useful insights about it. As I argued in the previous post, “Notes on Camp” is far more successful at describing a certain aesthetic constellation we’ll call “the campy” than it is in expounding true camp. For that kind of analysis, we should look to another critical luminary, a person whom Sontag admired so much that she assembled both the go-to “reader” of his major works and his most moving obit while, ironically, never making the camp connection. To be fair, Roland Barthes appears to have only once mentioned the word camp in his published writing (as an aside in a lecture at that), just months before his untimely death at the grill of a Parisian laundry van in the spring of 1980. But the paucity of reference doesn’t matter—perhaps, as Sontag says of the campy object, the best scholars of camp are “naïve” as to the nature of their own project.

Barthes, the French writer, philosopher, and academic best known for his work in semiotics, turns out to be the most advanced—or, more appropriately, nuanced—analyst of camp who has ever lived, at least if you read him my way. And indeed, an appreciation of “the nuance”—which at various points Barthes called the crease, the detail, the fold, the punctum, and the obtuse meaning—is the decoder ring essential for that reading. Wayne Koestenbaum, a cultural critic, poet, and contemporary acolyte of Barthes, explains the master’s relation to nuance thusly:

“Barthes had one lifelong mission, a messianic thread that connects his disparate ventures into the analysis of fashions, texts, and temperaments: the fight against received wisdom, obviousness, stereotype […] His gentle mission was to rescue nuance. What is nuance? Anything that caught Barthes’s eye. Anything that aroused him. Nuance—a shimmer beyond good and evil, beyond detection, beyond system—enjoys the privileges of a satiated passivity: it never combusts. Nuance offers not a substantive destination but a murmuring: ‘errantry does not align—it produces iridescence: what results is the nuance. Thus I move on, to the end of the tapestry, from one nuance to the next (the nuance is the last state of a color which can be named; the nuance is the Intractable).’ ”

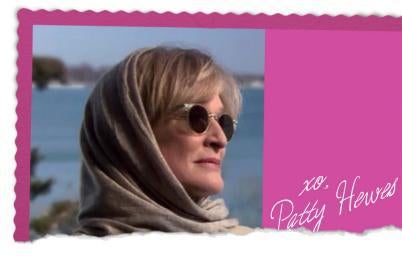

Let’s break that down. The nuance exists in opposition to “received wisdom, obviousness, stereotype,” and Barthes had a term for these nasty, imagination-binding shackles—doxa. Ignoring doxa in favor of the nuance, then, is an escape hatch, a secret passageway out of “the system” into a freer space of aesthetic engagement defined wholly by the eccentricities and proclivities of the reader, viewer, listener, whatever. Watching Glenn Close’s Damages, for example, may prove unpleasant if one isn’t already inclined to enjoy the doxical conventions of a legal procedural or family melodrama. But turn your attention to the nuance, and suddenly none of that stuff matters. The entire show—all five seasons of it—is suddenly justified by a single, tiny “crease”: the glint of Hamptons light on Patty Hewes’ bottle-cap sunglasses.

That’s my nuance, in any case; you might find a different one. The point is that I’ve evaded the doxa, slipped away from its demands of attending to “plot!” and “acting!” and “authorial intent!” and instead created my own little Zen garden landscaped entirely with the play of that light on that lens. Under the logic of the nuance, my miniscule “shimmer” is all that matters.

This kind of commitment, I’ll admit, can lead you to some strange places, like the time I maintained that the progression of Western art culminates in a picture of a dog shown briefly in the background of an episode of Archer.

A captured nuance

Archer still courtesy of FX

But thwarting the doxa is not possible without a little awkwardness, because while “obviousness” comes with prefab explanations, the nuance doesn’t arrive with a blueprint. There is no “why” to the nuance, no “meaning” lurking somewhere to elucidate how one came to choose it. Indeed, to ask after the meaning behind “the detail” is to miss the point entirely. The detail simply is; or rather, it is because your presence has made it so.

The following, for instance, are a few nuances that my presence makes so in Auntie Mame, the film discussed in the previous post whose campy appeal has aged while remaining open to camp:

- Mame’s pronunciation of child as ch-iiiile-duh.

- The bemused, seasick, and slightly cross-eyed expression that crosses Mame’s face when the nanny insists that she is “not that kind of woman.”

- The way Vera Charles drunkenly positions her coup glass, a la s’more, over the open fire.

- Mame’s request for a Sidecar and black coffee for breakfast. (She’s “hung” on the morning after the party, you see.)

Nuances in Auntie Mame

Auntie Mame still courtesy of Warner Bros.

But where, then, you might reasonably ask, is the payoff? Why toy with the nuance if it makes you such a solitary weirdo, going on about melting coup glasses and morning Sidecars? Enter camp. Mark Booth defined camp as “being committed to the marginal with a commitment greater than the marginal merits.” Pretty good. But camp is not itself the nuance; rather, it is the pleasure that seizing upon the nuance evokes. It is the shiver that travels down your spine when your unsuspecting finger breaches the crease, the electric jolt when the punctum suddenly pierces your field of vision. The best definition I can muster: Camp is the thrill of a whisper.

This, in the end, is what separates camp from the merely campy. Nuance can be found just about anywhere, from Sontag’s playfully “artificial” to the tragically serious (though certain conditions, as we’ll see, are more hospitable than others). By comparison, campiness is woefully limited in its reach. Moreover, unlike the campy, which has been mass-produced and played out to near death, camp—the pleasure of the nuance—is always fresh, forever sparkling in the eye of the beholder. The importance of this distinction cannot be overstated, not least because it quickly clears up so much of the confusion that has plagued discussions of “what counts as camp” in the past.