This article is part of Postcards from Camp, a multi-part series on the nature and contemporary relevance of camp sensibility. Read all of the entries here.

One of the very few things that Susan Sontag got right about camp is that it does not much care for the “linear, consecutive” confines of a traditional essay. This intractability results from the fact that camp is, as Sontag put it, “alive and powerful.” Taming its feline muscularity long enough for any meaningful inspection requires a form—like notes—that is “tentative and nimble,” firm yet flexible enough to accommodate the occasional writhing digression or frustrated nip.

But no one likes a copycat, so no notes here. And in any case, notes are impersonal, clinical; they have something of the condescension of armchair anthropology about them. As one of those camp natives who Sontag deemed too caught up in my own “sensibility” to evaluate it properly, I guess I couldn’t take objective notes on camp anyway. What I can do, however, is report from within it.

From within, because camp has volume. It has spatial dimensions; you can move around in it, visit different metropoles, hamlets, and backwaters. It boasts a remarkably diverse topography and expresses an array of distinct moods not unlike seasons. It has a complicated history and a set of (heartily disputed) origin myths. As a place, it is, of course, metaphysical, but also wonderfully, nauseatingly visceral. In short, camp is a country. (Kind of like Narnia, only here the White Witch is a drag queen named Turkish Delight and the animals take themselves far less seriously.) Many people pass through, some establish vacation homes, and a select few—like myself—become townies.

Unfortunately, what Camp does not have is an effective tourism office. Ever since Sontag’s slapdash observations attained the esteem of a Fodor’s guide, potential visitors have been fantastically confused about just what our town has to offer. Is camp a full-fledged aesthetic sensibility or a simple mode of humor? Is it a lens through which to view objects or an inherent property within them? Is it a subversive (gay) language or just another denuded subcultural trifle? We have had such poor public relations on these and other issues that some writers have recently gone as far as to declare us dead! (A bit dramatic for my taste, but given the aura of mystery surrounding camp, I don’t really blame them.)

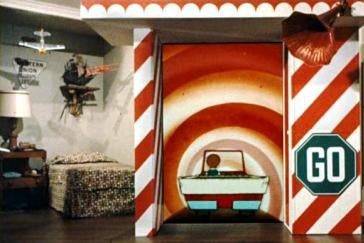

The good news is that camp is definitely not dead nor necessarily confusing. The bad news is that I don’t have a charmed wardrobe or a phantom tollbooth to bring you over and prove it. But here’s the next best thing: instead of notes, a set of travelogues—postcards from camp.

There’s no magical tollbooth for camp …

The Phantom Tollbooth still courtesy of MGM

This, then, is a letter of introduction. Hopefully, the posts that follow over the next few weeks will give you a sense of the wild and woolly landscape of camp (or at least the parts that interest me), just as a series of postcards convey the flavor of a trip without attending exhaustively to every detail.

I should mention that now is a fine time to be taking a jaunt through camp for a number of reasons. Aside from the grim rumors of its demise (which, while certainly scurrilous, are interesting for what they reveal about the mongers—more on that later), we are living in a moment in which the primary acolytes of camp—the gays—are supposedly (supposed to be?) leaving it behind. One of the most common and convincing understandings of camp is as a secret language and social currency of pre-Stonewall gay men. If, back then, you met a guy who thought Bette Davis was a laugh-riot in Now, Voyager, you could be fairly sure he was “family.” But we live now in the age of getting gay-married, being “Born This Way,” and counting ourselves part of the Modern Family—how could covert camp persist in this environment as anything more than a retrograde throwback?

Indeed, in the hours after Judy Garland’s funeral in June of 1969, many gay men seemed content to march down to Christopher Street and trade in their camp credentials for the dour political militancy of the post-Stonewall era. As David Halperin argues in his recent manifesto How to Be Gay, the whole project of the assimilation-directed gay civil rights movement of the past few decades is largely predicated on the suppression of queer quirks like camp. By that logic, old, mildewy camp should have burned off the moment the closet door swung open; yet, curiously, we’re still wading through its seductive musk 40 years later.

Why is camp holding on? What does it want? What do we want from it? Why are some so eager to relegate it to the cultural trash heap, and why, despite that morbid enthusiasm, do many others continue to feel its pulse? If, as Sontag suggests, camp is one of the two “pioneering forces of modern sensibility” (the other is apparently “Jewish moral seriousness”), isn’t it dangerous to kill it off so quickly? Surely we owe camp one final chance to prove its relevance before the shovelfuls of dirt begin to pile on.

What we don’t need is another tired debate about which things are or are not camp. To curate an exhibition of alleged contemporary camp artifacts would merely repeat the mistakes of our forbearers, for these, too, will likely fall from relevance as camp skips from fad to fad on into the future. Instead, the aim of these postcards will be to reimagine camp as a timeless practice rather than a perishable essence, a chosen point-of-view as opposed to an innate sensibility or concrete set of qualities. Certain camped objects, even whole camped styles, definitely have expiration dates (think of them as camp ghost towns) but big-C Camp, as a way of being in and understanding the world—or perhaps of remaking the world so it can understand your being—cannot die. No, camp will sempre viva, as the immortal Isabella Rossellini once put it.

At least we’d better hope so.

But I’m getting ahead of myself: First up on the safari slide show, the deliciously campy—and camp—world of Auntie Mame.