This article is part of Postcards from Camp, a multi-part series on the nature and contemporary relevance of camp sensibility. Read all of the entries here.

I once went on a date with a man who did not appreciate camp. His preferred sensibility was a nervous, punk-inflected disaffection, and I found it exotic, frustrating, and somewhat arousing. When I began to gather, over my second glass of riesling, that he did not much identify with the “gay stuff” that heavily defined my life, I asked him bluntly: “Are you, um, into camp?” He informed me that camp had sometime in the 1980s or ’90s morphed into “hipster irony” and been washed out by its diffusion into the general culture. New York was over, too; he would move to Canada soon.

I had heard this sigh of an argument before, of course, but it struck me as particularly disappointing coming from one ostensibly of my tribe, someone who by right of birth should “get” camp. In retrospect, though, I realize that my sadness was misplaced: We weren’t really talking about camp at all; we were talking about campy.

More on the difference between noun and adjective in a moment; but first, a bit of necessary history.

A key problem (probably the key problem) with camp: Sontag’s 1964 essay “Notes on Camp” was wildly influential. So influential, in fact, that even if you haven’t read it, those 58 little fragments have infected your mind as part of a larger cultural epidemic. You’ve picked them up on your fingers while leafing through the endless trove of film reviews, television recaps, “think pieces,” and newspaper articles contagious with throwaway lines like “campy performance” and “camp appeal.” You’ve heard that Pink Flamingos or American Horror Story or Lady Gaga is “campy,” inferred that the word must indicate a certain feral, transgressive, winking decadence, and caught Sontag’s nasty little bug. But it’s not your fault—there has never been an inoculation distributed widely enough to combat Sontag’s potent formulation. Her intoxicating brew of detached authority, stylistic showmanship, intimidating intellectual name-dropping, and mysterious subject matter—all distilled, it should be remembered, under the not unhelpful auspices of the Partisan Review—ensured that Sontag would corner the market on camp. Indeed, she would become, as literary critic Terry Castle has written, its “philosopher” for the subsequent decades.

Unfortunately, the majority of “Notes on Camp”—past the part where Sontag rightly defines camp as “one way of seeing the world as an aesthetic phenomenon”—is actually concerned with what I’ll distinguish as campiness or the campy. Campiness, as a style and sensibility, comprises a set of widely appreciated characteristics: frivolity, the celebration of the “so bad it’s good,” the overwrought, the histrionic, what Sontag calls “failed seriousness.” It’s standard midnight-screening fare. But these characteristics are not at all intrinsic to camp. In other words, camp is not the same thing as campy, and the latter, as a popular aesthetic, may well be fading into obscurity while the former, a “way of seeing the world,” soldiers on.

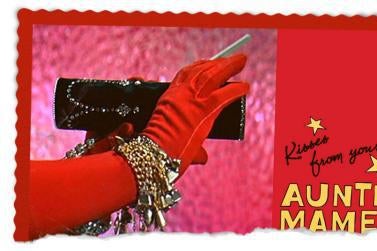

To understand this crucial difference, let’s turn to a film that is rich with both camp and campy potential—the 1958 classic Auntie Mame. Rosalind Russell stars in the title role as a wealthy, bohemian New York auntie determined to raise her newly orphaned nephew to resist the pressures of WASP conformity emanating from the rest of his family. While the entirety of the two-and-a-half hour film is worthy of study (preferably in the rakish company of Mame’s eye-opener, the Sidecar), the early sequence during which young Patrick and Mame initially meet contains more than enough material for our purposes.

Using Sontag’s framework—that camp is interested in artifice and exaggeration, in the absurd and “off,” in style over content—it’s easy to see what’s campy here. When Patrick and his nanny approach Mame’s apartment door, they are greeted with a smoke-breathing dragon peephole that only hints at the elaborate oriental decorative fantasy waiting within. Once through the portal, they find a gin-fueled “affair” populated by a delightful mix of revelers suggesting a flapper-era superimposition of French salon and Studio 54 (campiness loves superimposition, especially when it’s anachronistic.) As Mame glides down the grand staircase brandishing an oversize cigarette holder and exclaiming “dahhhling!” this and “adorable little bootlegger” that, there’s no doubt that the tone is campy in the extreme. Much of the rapid-fire dialogue that follows is so nimble that you need multiple viewings to catch every witticism, but that’s in some sense by design: The stylistic effect of Mame’s frenetic chic is far more important than the specifics of what she’s actually saying. The point of this sequence, and indeed, the entirety of Auntie Mame, is to conjure a mood of madcap, jovial delight, to fuel a frolic at turns sassy and tender, but always light-hearted. It is, in a word, campy.

But as effervescent as Mame remains in my personal estimation, most contemporary viewers probably find it a little flat. Comedy at this late date depends, of course, on exhausting knots of irony, and—if Louie, Girls, and similar hits are any indication—an increasingly thick thread of self-deprecation fraying into outright abjection. By comparison, Auntie Mame feels altogether too forthright, too polished, and, most importantly, too sincere in its joyful exuberance to pass the smell test. Mame is the kind of character you’d imitate (think of April Ludgate on Parks and Recreation) now not because her campiness is authentically entertaining, but rather because putting on such an arch-aristocratic accent simultaneously conveys a certain cultural knowledge, an embarrassed self-consciousness of that knowledge, and, mediated through “hipster irony,” a half-hearted apologia for that knowledge. We want people to know that we know what we know is maybe not authentically cool enough to know even as we can’t help but let them know that we know it. And lodged somewhere within all this tortured choreography, I’m told, is fun.

Suffice it to say, Mame’s campiness doesn’t translate well to the current vernacular, but fortunately that doesn’t mean it needs to be tossed. The film still has camp appeal to recommend it: You only need to know where—or better, how—to look. Tomorrow, we’ll revisit Mame’s affair, this time scouring it with a fine-toothed, jewel-inlaid ivory comb in search of the real thing.