When Matt Lauer was fired last month, TMZ dug up a 2012 clip from the show Watch What Happens Live, in which Katie Couric told Andy Cohen that her then–co-host Lauer’s most annoying habit was “he pinched me on the ass a lot.” Cohen and the audience laughed, and that was the end of it. How is it possible that we thought this was funny so recently? The answer is in our history.

Between the turn of the 20th century and the advent of second-wave feminism in the 1970s, men took the uneasiness they felt about the incursion of “respectable” women into formerly male office spaces, and made it into comedy. The most firmly established genre of “women in the workplace” humor is the secretary joke, in which a lecherous boss or co-worker “flirts” with a woman by pursuing her around an office or making cracks about her body. Although it’s largely outdated now, this venerable tradition in American humor underlies and informs the uncomfortable laughter that Couric’s admission provoked.

Historian Julie Berebitsky, who wrote Sex in the Office: A History of Gender, Power, and Desire, told me that she chose to research the history of secretaries, stenographers, and typewriters because their entry into the office in the early 20th century was a watershed moment in gender relations. For the first time in American history, many middle-class women were sharing workspaces with men. Poor women, who had long worked alongside men in factories, in domestic service, and in slavery, were abused as a matter of fact, and their abuse was generally of little note. Secretaries, on the other hand, were well-educated women who might be accorded some respect, Berebitsky said. The tension between this expectation of respect and women’s new status as co-workers became a source of uneasy humor. Newspapers ran funny secretary stories; advertisements for office products played on sexy-secretary stereotypes; the plots of movies featured gold-digging secretaries on the make.

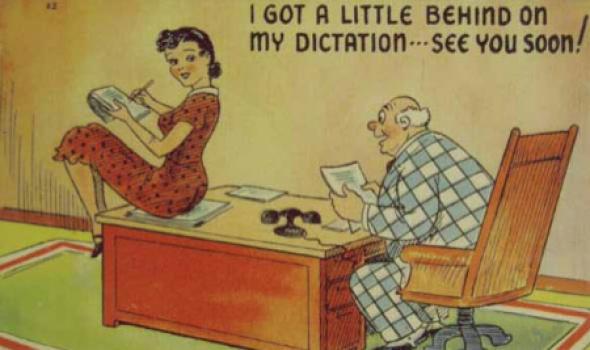

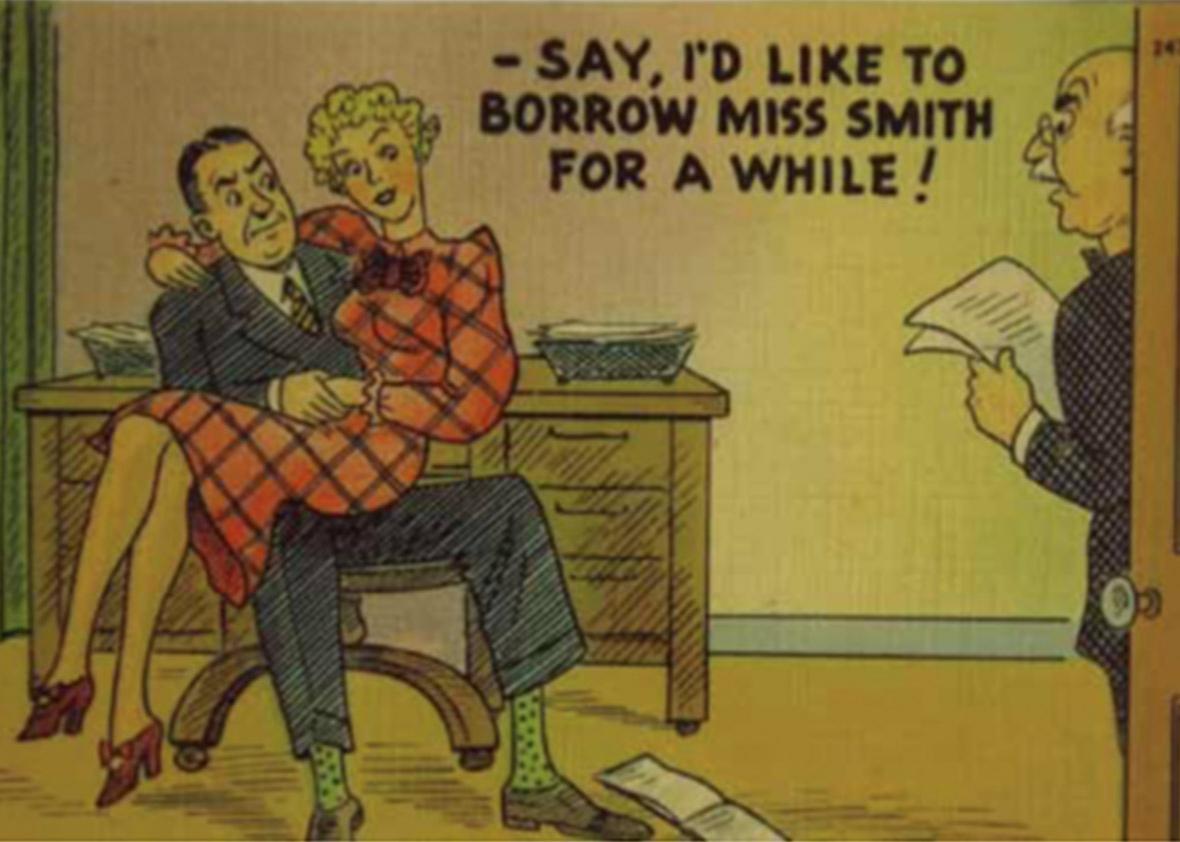

Berebitsky collected comic postcards from the middle of the 20th century that featured men in suits—often older men, with bald heads and preposterous fringes of hair—appreciating the view of a woman sitting on a pile of papers on his desk (“I got a little behind on my dictation…see you soon!”) or chasing comely secretaries around offices (“This overtime work is keeping me thin!”) “The Chase” was to become a trope of this kind of boss-secretary humor, and it crossed over between popular representations and real life. In her 1964 book Sex and the Office, Helen Gurley Brown remembered a tradition called “Scuttle,” in which workers chased down a secretary and took her underwear off. (When Mad Men included this game in an episode, the show actually toned it down, making the goal to see a colleague’s panties, rather than strip her of them.) Brown recalled this chase game fondly—proving, once again, that internalized misogyny is a hell of a drug.

From the collection of Julie Berebitsky

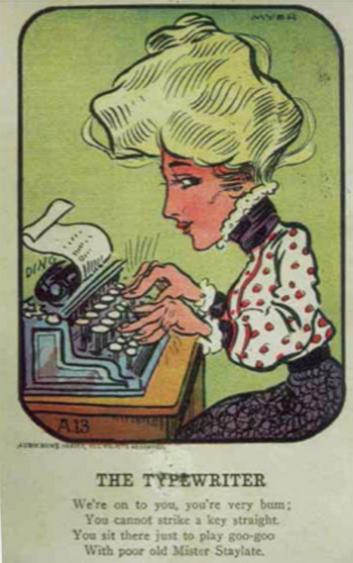

The idea that the stenographer or secretary was in the job only to find a husband was widespread. A group of postcards Berebitsky collected from the early 20th century mocked secretaries from the point of view of the threatened boss’ wife. One such card, titled “The Typewriter,” offered the following verse: “We’re on to you, you’re very bum; You cannot strike a key straight/You sit there just to play goo-goo/With poor old Mister Staylate.” Some secretaries did marry their bosses—after all, as Berebitsky said, “If you were a stenographer, you had no way to get anywhere beyond being a stenographer,” since there was no career ladder to climb up from that job. “As you got older, if you didn’t have a husband, you’d be poor.”

Young, pretty women had a much easier time getting jobs in the field. Berebitsky found that as early as 1895, women recognized the perils of this dynamic. An article in a stenography journal published that year detailed the Catch-22 secretaries faced: Attractive women, Berebitsky wrote, “would have to fend off their employers’ dinner invitations,” while less attractive women “would have a difficult time landing a position or securing a promotion.” Jokes about the secretary out to catch a man—a staple of this kind of workplace humor from an early date—punished women for being caught in a system that sexualized them.

The bosses in the popular depictions of boss–secretary sex were often older, pointing to the fact that employing a pretty secretary you were having sex with was perceived as a privilege of power. Berebitsky cites an ad that ran during World War II, depicting a secretary sitting in the lap of a balding man, both drinking Pepsis, with the caption: “He says as long as he’s going to be tied to a desk for the rest of the war, he might as well relax and enjoy it.”

From the collection of Julie Berebitsky

Midcentury jokes skewered secretaries’ skills as well as their bodies. Milton Berle, the comedian who hosted the enormously popular TV show Texaco Star Theater in the 1940s and 1950s, made secretary jokes that were about sexuality (“I know a boss who’s so dedicated he keeps his secretary at his bedside all night in case he wants to send a letter!”) But they were also about secretaries’ lack of aptitude at their jobs: “My secretary saves me money. She orders correction fluid by the six-pack!” “My secretary is great in math. She added up a column of a dozen numbers 10 times and showed me all 10 answers!”

The dumb secretary was everywhere and made sexier by her stupidity. A Jack Davis Playboy cartoon, selected by Hugh Hefner in 2004 for a 50-year commemorative volume of such art, had the beautiful “Miss Turnbull” strutting bare-chested past a group of excited office colleagues. The gag: Her boss had asked her to “get rid of that sweater, please” because it was “distracting the men in the office,” and she, not understanding, took the sweater off altogether. Another Playboy cartoon, by Jack Sneyd, featured a personnel manager looking at a Playboy centerfold while a pretty young woman in his office smiled at him: “Quite an impressive resume, Miss Simmons!” The women in the office are there for decoration and intrigue. Their inefficient brains are a trial men would put up with in order to continue to have access to their bodies.

In the seventies, feminists started protesting secretary jokes. A flyer from the first sexual harassment speak-out in 1975 was headlined “Is This Really Funny?” and reproduced a comic that depicted a variation of The Chase: a man in a suit pursuing a woman who’s saying “My dictation speed is 40 mph!” Berebitsky notes that the activist group Women Office Workers of New York published a newsletter that called out objectionable ads, jokes, and TV shows as submitted by members. In 1972 the secretaries’ objections to “stereotypes” made the New York Times. Judy Blemesrud described the image the women were combating in a memorable lede: “Gum-chewing sex kitten; husband hunter; miniskirted ding-a-ling; slow-witted pencil pusher; office ‘go-fer,’; reliable old shoe.”

Feminists had some success challenging these representations. In 1971, the 21-year-old comic strip Beetle Bailey introduced a secretary named Miss Buxley who was, Cullen Murphy wrote in the Atlantic in 1984, “a lissome airhead.” Buxley’s boss, General Amos T. Halftrack, forgave her for her many errors because she was so pretty. Murphy wrote on the occasion of cartoonist Mort Walker’s decision to upgrade Miss Buxley—to cover her up, give her a “brain.” Walker told Murphy it was feminism that forced his hand—readers wrote letters to newspapers, and newspaper staffers pressured their editors to refuse to publish the strip when Miss Buxley made an appearance. Walker wasn’t happy about it. “The cartoonist’s fondest wish, at this point,” Murphy wrote, “is for ‘the feminists to get off my back.’ ”

If the ditzy secretary stereotype couldn’t weather the years when second-wave feminism was at its height, the trope of “The Chase”—an aggressive man using his workplace as a hunting ground—was more durable. When the Clarence Thomas hearings aired on television in 1991, almost 20 years after feminists began to make their case against the Miss Buxleys of the world, many sexual-harassment plotlines still drove sitcoms. TV critic Tom Jicha observed at that time that Sam Malone, played by Ted Danson on Cheers, was totally “relentless” in his pursuit of sometime-employees Diane and Rebecca, and in both cases his relentlessness was rewarded. Jicha also cited Major Dad, Murphy Brown, L.A. Law, and Taxi in a list of shows featuring aggressive, lecherous men whose inability to take “no” for an answer in the workplace was a bottomless well of comedy.

From the collection of Julie Berebitsky

I’d like to think we’re doing better now. More recently, TV comedy has used the nature of workplace harassment—the murkiness of its definition; the awkwardness that springs up when women resist it—as fodder. This gives me some hope that harassment comedy overall might be taking a turn for the self-aware. In a 2005 episode of The Office titled “Sexual Harassment,” Michael Scott (Steve Carell) is furious when the office’s HR guy, Toby Flenderson (Paul Lieberstein), wants to review the company’s sexual harassment policy with the employees.* Michael is convinced that a conversation about sexual harassment will mean “the end of jokes.” “There is no such thing as an appropriate joke,” he whines to Toby. “That’s why it’s a joke.” Though he’s clearly clueless, in the end, Michael gets a pass. He never completely wrecks our loyalty to the character—or the loyalty of his employees, who by all rights should have reported him or quit a million times over. They are annoyed, but never truly oppressed, by his “sense of humor.” Michael is completely tone-deaf, the office consensus goes, but ultimately harmless. His boorish buddy Todd Packer (David Koechner) shows up in this episode to illustrate how totally unfunny “true” harassers can be.

In the past few decades, the clumsy innuendoes of clueless bosses have begun to look more and more embarrassing and dated. The Onion ran a point/counterpoint piece in 1998: “Sexual Harassment in the Workplace Must Stop vs. I Love The Way Your Tits Bounce When You Type.” In that spoof, after the feminist Nadine Kramer-Luchs has her earnest say, op-ed writer Bruce Mulholland defends his position: “Sure, you may not be the brightest bulb we’ve ever hired for this position but hey, with a body like yours, secretarial skills aren’t really a priority. And speaking of positions, I don’t know about your performance in this position, but I’d love to see how you perform in a couple of others that come to mind. Arooga!”

Bruce Mulholland, that florid caricature, is the butt of the joke. He has something in common with Mr. Henderson, the boss played by Tim Heidecker in a recurring bit on the sketch series Tim and Eric Awesome Show, Great Job! Mr. Henderson sexually harasses his employee, Carol, played by Heidecker’s co-star Eric Wareheim (in an extremely wince-inducing fat suit). In one such sketch, Mr. Henderson stands by Carol’s desk and issues a stream of commentary: “I gotta admit something, Carol. I am getting hot around you. I just like the way your body looks. You’re turning us all on over here, OK. Going nuts. I wanna get in that. You’re looking hot, H-O-T.”

And so on, and so on, and much dirtier. Time, for the viewer, stretches painfully, just as it does when you’re a woman enduring such a performance in real life. The fact that Carol happens to have a crush on Mr. Henderson ruins the commentary—or does it? Is Carol’s affection perhaps meant to double down on the joke, to show how ridiculous such a reciprocation would be in real life?

In recent weeks, plenty of comedians have managed to satisfyingly skewer Weinstein in ways that were pointed and funny. But these subtler, fresher takes aside, it’s clear that the cheesy old-school hot secretary/lecherous boss joke is still around. You can find them all over internet forums that post user-submitted humor, like netjokes.net or kickasshumor.com, though such gags aren’t simply the province of amateur jerkoffs. As recently as October, James Corden made light of Harvey Weinstein’s chase tactics while emceeing a gala, with quips including: “It’s a beautiful night here in L.A. It’s so beautiful, Harvey Weinstein has already asked tonight up to his hotel to give him a massage.” Weinstein’s accusers, particularly Asia Argento and Rose McGowan, found Corden’s routine infuriating. Their anger at these anodyne-seeming goofs becomes easier to understand when you consider how often in our history toothless jokes about workplace sex that paint the harasser as a bumbling, benign lech have helped keep women in their place. An ass-pinch or a hot-body jest aren’t low-stakes. They give a woman who’s just trying to work an impossible choice: Go along to get along, or murder the moment by stepping into the role of feminist killjoy. This fall, more and more of us seem to be choosing the latter.

*Correction, Dec. 20, 2017: This article originally misstated when this episode of The Office aired. It was 2005, not 2002. (Return.)