Thirty years ago this week, Kathryn Bigelow’s film Near Dark prowled its way into theaters. Bigelow’s first solo directorial outing was a poetically violent horror film about a young cowboy lured into the vampire underworld by a mysterious woman. It was not, however, the only boy-meets-vampire-girl movie of 1987. The Lost Boys hit theaters just months prior to Near Dark, aimed directly at the teen market: It was set at the beach, packed with up-and-coming stars, and featured INXS on the soundtrack.

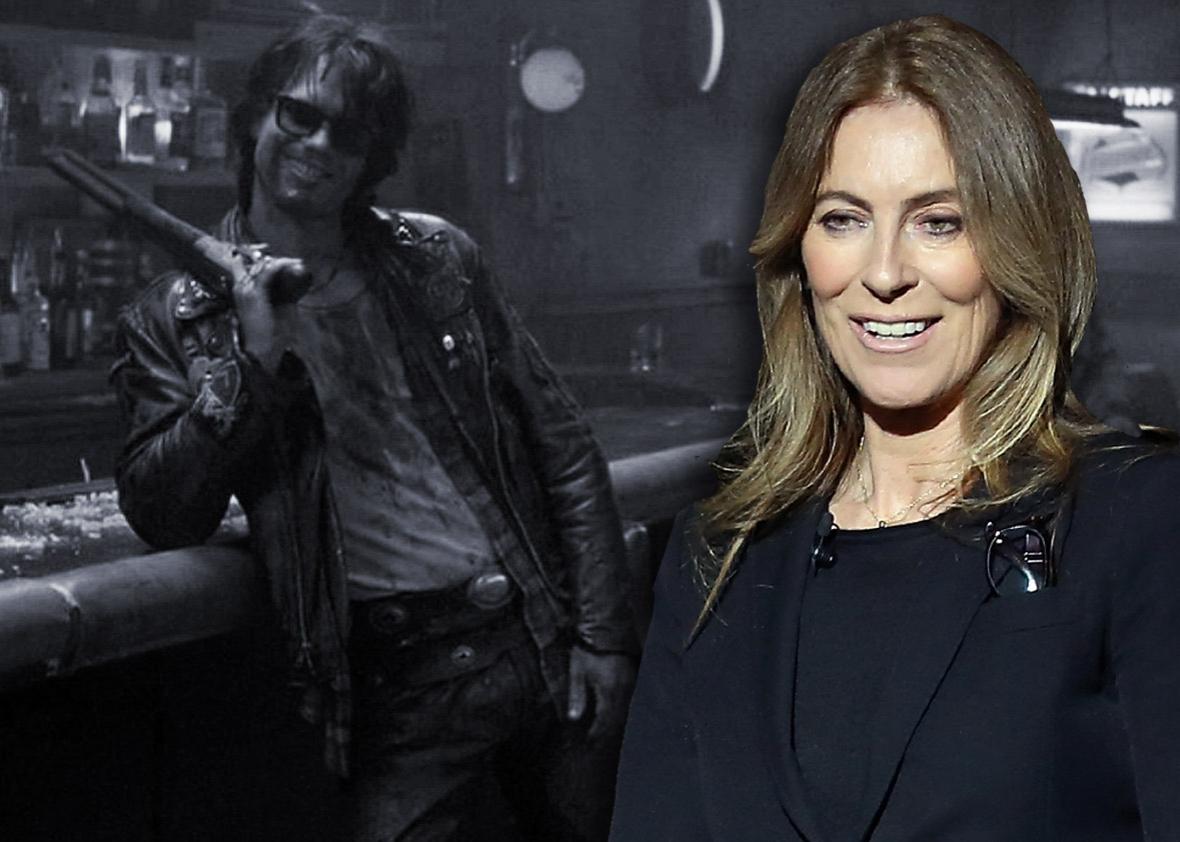

Bigelow’s film, meanwhile, was set in Oklahoma, starred three actors from the movie Aliens (plus the creepy kid from River’s Edge), and had a score by German electronic band Tangerine Dream. It’s not hard to guess which film was a box office success and which one became a cult classic. Three decades later, though, The Lost Boys is a sexy sax man meme, and Near Dark remains one of the best American vampire films ever made, an essential horror rewatch for our Trumpian times and an exemplar of the work that’s made Kathryn Bigelow one of the most successful female directors of all time. Near Dark is a genre film of surprising nuance, full of well-drawn characters and moral complexity that catches you unaware with insights on its cultural context. Watching Near Dark in the wake of Bigelow’s Detroit underlines what’s missing in Bigelow’s latest film and why Detroit fell so short of her good intentions.

Near Dark centers on Caleb Colton (Adrian Pasdar), a young cowboy who wishes he were a thousand miles away from his Oklahoma town. One night while he’s out with friends, Caleb offers a lift to an alluring young woman named Mae (Jenny Wright). As the attraction between them builds to a kiss, Mae nips Caleb in the neck and runs off. Before he can make it home the next morning, Caleb gets picked up by Mae’s family, the menacing Southern patriarch Jesse Hooker (Lance Henriksen) and his progeny: psycho cowboy Severen (Bill Paxton), Jesse’s companion Diamondback (Jenette Goldstein), and Diamondback’s “son” Homer (Joshua John Miller), an angsty teen who is actually decades old. Caleb discovers that he’s been “turned,” and as he struggles to become a killer like the rest of Mae’s family, Caleb’s human father (Tim Thomerson) sets out to track him down.

The term vampire is never uttered in Near Dark; there are no crosses, coffins, or vials of holy water to be seen. Mae’s family brandishes guns and switchblades, sleeps in abandoned buildings and cheap motels, and travels by vans and RVs with blacked-out windows. Near Dark’s blend of horror, Western, and action was not just a departure for vampire films, but it was also a perfect proving ground for Bigelow’s signature brand of kinetic filmmaking. During a shootout between the vampires and the police, bullets pierce the walls and windows of a cheap motel bungalow, and sunlight cuts through the room like laser beams, searing into the vampires’ flesh.

But even though Bigelow stripped away the gothic trappings that had been central to vampire films for decades, Near Dark is still all about blood, and in particular how blood ties families together. Mae’s family is, in many ways, the epitome of an intentional family, a feat that Bigelow achieves partly through a clever trick of casting: Henriksen, Paxton, and Goldstein had all just finished working together in the ensemble for James Cameron’s Aliens. (At one point in the film, Aliens actually appears on a movie marquee in the background.) It’s fascinating to see the camaraderie developed by these actors for a war movie reshaped into familial devotion by Bigelow.

In order to earn his place in Mae’s family, Caleb has to shed blood; until he learns to kill, he’s just another mouth to feed. For all their freedom and near-indestructability, the vampires in Near Dark are barely scraping by: consigned to the margins, always hungry, and living hand to mouth. They are a monstrous embodiment of poverty. In most vampire films, hunting for food often involves mystery and seduction; in Near Dark, it mostly means exploiting the kindness of others. In one particularly horrifying scene, Homer pretends he’s the victim of a bicycle accident to feed off the good Samaritan who stops to help.

Throughout the film, we see glimpses of a Confederate flag stitched into the lining of Jesse’s coat. When Caleb finally asks Jesse how old he is, Jesse responds, “Let’s put it this way: I fought for the South.” A moment later, Jesse adds, “We lost.” It’s a moment that inflects Jesse and his progeny with potent symbolism: Jesse is an undead embodiment of the antebellum South, who subsists by sucking the lifeblood out of the working- and middle-class people—including the few people of color in the film—that he and his family encounter in the heartland of America.

When Near Dark hit theaters, American politics, media, and pop culture were preoccupied with demonizing urban poverty. Conservative politicians raised the specter of welfare queens and crack babies to point to the decline of urban families; media over-represented black Americans in depictions of poverty; films ranging from Lean on Me to Robocop to Colors portrayed inner cities as dangerous, gang-ridden hells. All of this exploited and contributed to fears that poor people of color in urban cities were leeching off hardworking, tax-paying whites in Middle America. But Near Dark imagined that America’s real vampires were poor Southern whites who saw themselves on the losing side of American history. Near Dark tapped into those below-the-surface fears that poverty and decline could harm whites in Middle America and that the infected are all the more monstrous because they don’t look like what you’d expect.

Rewatching Near Dark a few months after Charlottesville, in a media landscape obsessed with the cultural grievances of Trump’s white working-class supporters, it’s hard not to find Bigelow’s vision of American vampirism particularly chilling and prescient. It’s odd, but also perhaps telling, that Bigelow’s 30-year-old horror movie seems to offer more insight into our current moment than Detroit does: In her effort to painstakingly dramatize the horrific events of the Algiers Motel, Bigelow inadvertently reduces her characters to simple villains and victims. Detroit becomes a horror show about racial injustice, rather than an illumination of the cultural forces that drive it. Near Dark, like all the best horror movies, shines a light on the cultural forces that are really lurking in the shadows.

Within the film’s cultural context, Severen emerges as a vicious and cruel model of unchecked white male aggression. It’s a role Bill Paxton seemed born to play. Paxton made his name in the 1980s playing tough guys, bullies, and military grunts with uncharacteristic insight. He understood the fragility of their hypermasculinity, and when his characters were humbled, or when their bravado turned to fear, it was not so much a reversal as a reveal. In Paxton’s hands, Severen is the pathological result of what happens when a tough guy feels bulletproof because he is bulletproof. In the most memorable scene of Near Dark, Severen taunts and tortures the patrons of a country bar (which Severen gleefully refers to as “shit-kicker heaven”) and encourages Caleb to explore the full benefits of his newfound strength and power. While a menacing, psychobilly cover of “Fever” by the Cramps plays from the jukebox, Severen’s back-slapping, good-old-boy jokes become a long, sadistic setup for a slaughter.

As Caleb’s vampire and human families converge in the film, Caleb finds himself torn between fathers. Loy Colton and Jesse Hooker possess many of the same values—both are proud providers, deeply devoted to and protective of their offspring—but the way each makes a living is night and day: Loy is a large-animal veterinarian, a man who supports the farmers and ranchers who could easily fall victim to Jesse. The chief question facing Caleb is which bloodline is stronger: human or vampire? What kind of man will he grow up to be?

Bigelow has earned a reputation for making great, muscular films about men, and Near Dark is no exception. But her exceptional female protagonists are revealing, too. Jamie Lee Curtis’ rookie cop in Blue Steel; Lori Petty’s orphaned surfer in Point Break; Jessica Chastain’s intelligence analyst in Zero Dark Thirty: Whether by preference or necessity, these women are locked in worlds that are dominated by men. In Near Dark, Mae and Diamondback are equal to the men in their vampire family, but they are clearly part of Jesse and Severen’s world—not the other way around. Bigelow’s female protagonists are always powerful, but they’re often lonely. When Mae tells Caleb at the beginning of Near Dark that he’s never met a girl like her, her sense of loneliness seems almost acute. This director, who began her career when women directing action or horror films were even more rare than today, has regularly explored the experiences of women who’ve had to navigate the worlds of men by themselves.

Thirty years ago, there was no pathway for women who wanted to make the kind of high-impact, action-driven dramas that intrigued Bigelow. She had to chart her own course to direct Near Dark. She teamed up with Eric Red, who had written the script for the thriller The Hitcher, and they co-wrote two screenplays: Near Dark, to be directed by Bigelow, and Undertow, to be directed by Red. Bigelow landed Near Dark first, but it was not without strings attached. In a 2010 interview with the L.A. Times, she noted that the producer of the film gave her the job under the condition that he had the right to fire her after the first day of dailies. One might be tempted to assume that James Cameron had a hand in getting Near Dark off the ground, given that the film had so much overlap in cast—as well as the fact that Bigelow and Cameron were married for two years starting in 1989, and they worked together on two other films. But Cameron had no input on Near Dark—including the casting. Bill Paxton shared the script with Lance Henriksen, and Bigelow auditioned all three actors before she contacted Cameron to see if he minded her using so many Aliens actors.

While watching the credits roll on the VHS copy of Near Dark I rented as a young teenager, I realized that I couldn’t recall ever seeing another woman listed as a film director. A strange and atmospheric vampire film full of gunfights and metaphors about American identity seemed even more radical, more unlikely, because a woman brought it to life. The only thing I didn’t like about Near Dark at the time was its ending: Caleb vanquishes Jesse and Severen and manages to reverse the vampirism afflicting him and Mae by transfusing his father’s blood. At the time, it felt too clean, too patriarchal—too conservative. It’s an uncharacteristically happy ending for a Bigelow film. It bothers me less today, though. Happy endings are in short supply at the moment, and we’d all like to vanquish the monstrous legacies of America’s past and feel like there’s daylight ahead.