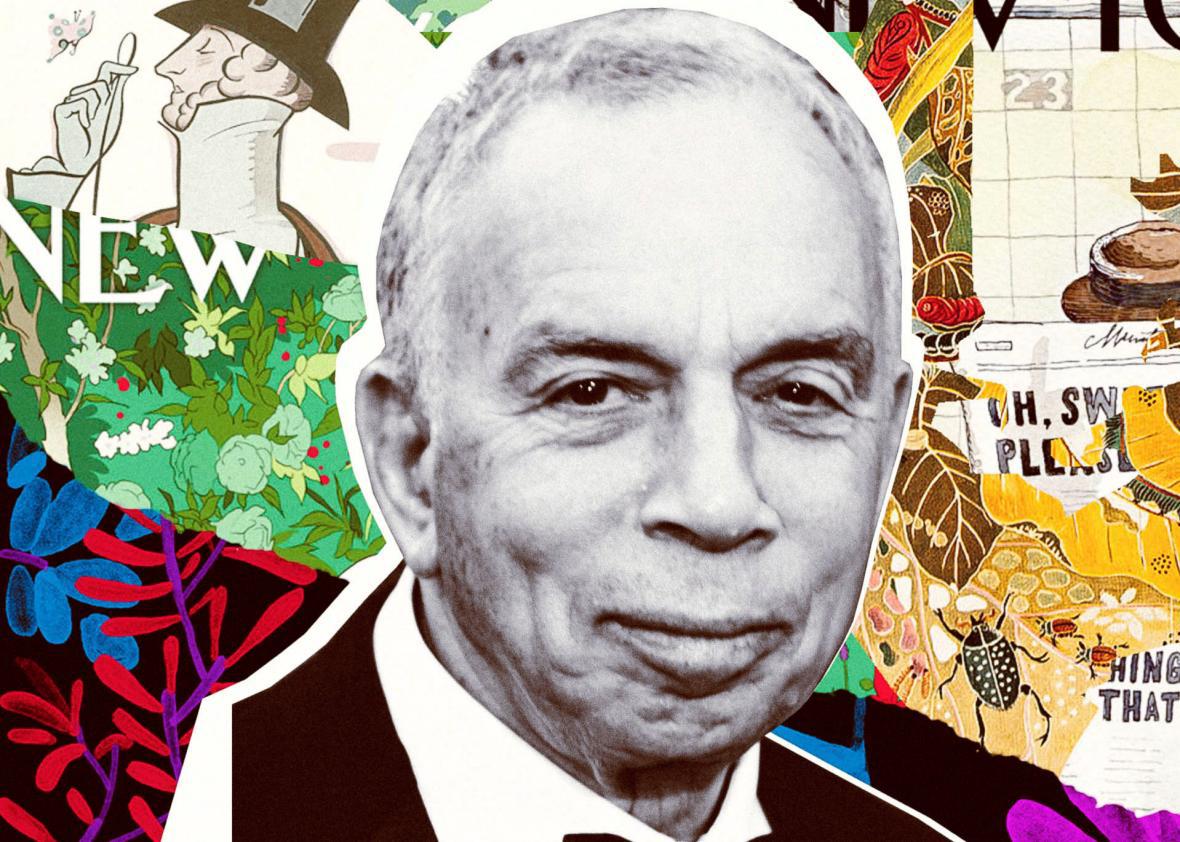

In the middle of this season’s howling news storms, the death of S.I. Newhouse Jr. passed almost unnoticed, for the Condé Nast publisher had reached a venerable age, lived without scandal, and seemed to pass with his affairs in order. But the obituary struck me hard—it was a cautionary reminder of a moment when I’d been very sure of myself, and more wrong than right.

My first job out of college was writing Talk of the Town stories for the New Yorker. In those days, the short pieces were anonymous, and for about half a decade, I was their most prolific author. Some weeks I wrote most of the section, often alternating authorship of the political editorial called Notes and Comment with Jonathan Schell. This was the early 1980s, the last years of William Shawn’s tenure as editor. Mr. Shawn had run the magazine for a very long time as it became the nation’s pre-eminent publication—at its height, ad agencies had celebrated when they were allowed to buy space in its crowded pages. He maintained an inviolate separation of the magazine’s business and editorial staff—presidents go to church, but writers for the New Yorker were literally not allowed on the advertising floors, and vice versa. There was not even an interconnecting staircase.

This was understood by all to be rare, and by most to be essential to the magazine’s literary success. But the owners who had allowed this division, the yeast magnate Raoul Fleischmann and his family, eventually decided to sell. The buyer, Si Newhouse, was a newspaperman who had begun what became a nationwide empire in Staten Island. He was not a flashy tycoon, but he had let it be known that, in his opinion, the time had come for Mr. Shawn to begin stepping aside and also—here was the crux—that he did not intend to let him pick the next editor.

In every nondemocratic government, succession is a problem: Carefully constructed arrangements and unwritten rules are suddenly at stake. There was no obvious in-house heir apparent: Mr. Shawn had long hoped Schell would succeed him, but that was opposed by many on the staff. (There was a brief period when he decided that perhaps I should be the chosen one, a poor idea in too many ways to count, though at 25 I was not mature enough to understand them all.) In any event, when Newhouse named Knopf editor Robert Gottlieb as the top man, it sparked a short but intense rebellion. There were impromptu meetings of all the writers in the stairwell; a delegation was named to compose a letter to Gottlieb imploring him to turn down the job in the interest of maintaining “editorial independence,” which became the rallying cry. And so forth. I ardently supported all this activity—Newhouse’s decision seemed to me the usurpation of a noble order by a crude outside commercial force, one that would inevitably corrupt it. I quit, and so did Schell.

I’ve never regretted that decision—if I hadn’t made it, I might well have spent my life at the New Yorker, and that would have prevented many other adventures. But I was, in the end, wrong about that usurpation. Yes, Gottlieb, and especially his successor, Tina Brown, at first made the New Yorker less special; they were chasing the same stories, in the same ways, that New York or the Times Magazine would have done—which was fine but duplicative. In those years, the momentum of the magazine, and the skills of the staff of writers, editors, and checkers who kept to their task, were enough to keep it a worthwhile read. But with the hiring of David Remnick in 1998, Newhouse chose an editor who has now spent decades of his own quietly producing a magazine that is once more without equal. It is not great in the same way that Mr. Shawn’s was (and no magazine will ever again have the same kind of cultural dominance), but it is great in a different way, both attuned to its era and ungoverned by it.

And it is a weekly reminder to me that all rules have exceptions. I think it is fair to say that most men of great wealth have behaved in unproductive ways in recent decades, gaming our political systems and using the power of their various corporations to advance their own interests at the expense of workers, customers, and societies. But not all. Si Newhouse seems to have decided that the New Yorker was worth protecting, and that the way to protect it was to get out of the way. Remnick has written that he was left alone to manage the magazine. If it has become more business-savvy, sponsoring festivals and so on in a way that would have embarrassed Mr. Shawn, none of that seems to have diminished the quality or the integrity of the words on the page (or, as Mr. Shawn never could have imagined, on the screen). It would have been easy, I would guess, for Newhouse to find more lucrative returns for his money, and indeed at other institutions like Gourmet he acted ruthlessly. But the New Yorker was not cut back to a biweekly, or reduced to putting out special commemorative issues, or given over to “native advertising.” It was allowed to make its way.

Magazines like the New Yorker could not be built, I don’t believe, in the present information economy—they can only be preserved. And so the custodians of those institutions are crucial, and deserve to be celebrated. There are others doing similarly good work: Rea Hederman at the New York Review of Books, for instance, who seems to have set that unlikely and necessary venture on sound financial and operational footing. Or the Sulzbergers at the New York Times. I worry, of course, that the new owners of the New Yorker, whoever they are, won’t have the same shrewd understanding of what makes the steady, wise, and—in its own modern fashion—beloved New Yorker tick. But then, I fretted the same frets about Si Newhouse, and I was wrong.