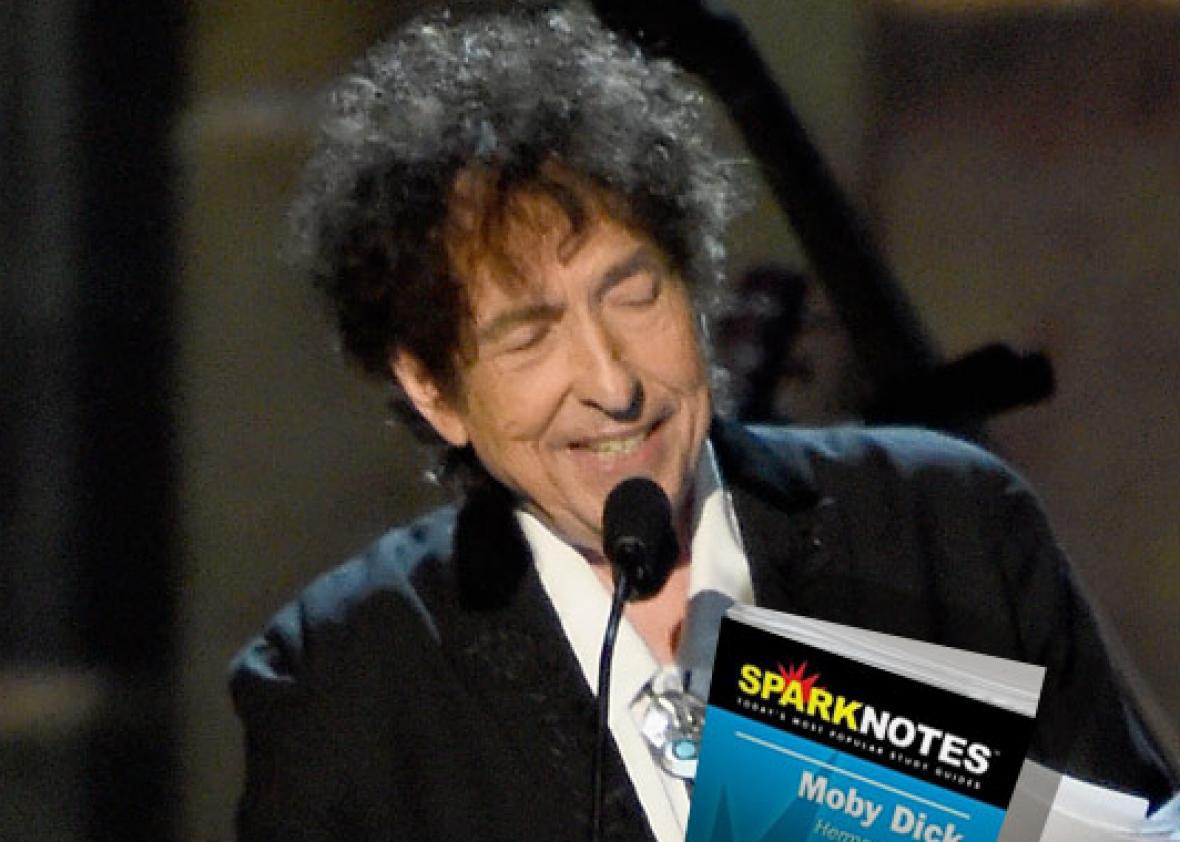

If a songwriter can win the Nobel Prize for literature, can CliffsNotes be art? During his official lecture recorded on June 4, laureate Bob Dylan described the influence on him of three literary works from his childhood: The Odyssey, All Quiet on the Western Front, and Moby-Dick. Soon after, writer Ben Greenman noted that in his lecture Dylan seemed to have invented a quote from Moby-Dick.

Those familiar with Dylan’s music might recall that he winkingly attributed fabricated quotes to Abraham Lincoln in his “Talkin’ World War III Blues.” So Dylan making up an imaginary quote is nothing new. However, I soon discovered that the Moby-Dick line Dylan dreamed up last week seems to be cobbled together out of phrases on the website SparkNotes, the online equivalent of CliffsNotes.

In Dylan’s recounting, a “Quaker pacifist priest” tells Flask, the third mate, “Some men who receive injuries are led to God, others are led to bitterness” (my emphasis). No such line appears anywhere in Herman Melville’s novel. However, SparkNotes’ character list describes the preacher using similar phrasing, as “someone whose trials have led him toward God rather than bitterness” (again, emphasis mine).

Following up on this strange echo, I began delving into the two texts side by side and found that many lines Dylan used throughout his Nobel discussion of Moby-Dick appear to have been cribbed even more directly from the site. The SparkNotes summary for Moby-Dick explains, “One of the ships … carries Gabriel, a crazed prophet who predicts doom.” Dylan’s version reads, “There’s a crazy prophet, Gabriel, on one of the vessels, and he predicts Ahab’s doom.”

Shortly after, the SparkNotes account relays that “Captain Boomer has lost an arm in an encounter with Moby Dick. … Boomer, happy simply to have survived his encounter, cannot understand Ahab’s lust for vengeance.” In his lecture, Dylan says, “Captain Boomer—he lost an arm to Moby. But … he’s happy to have survived. He can’t accept Ahab’s lust for vengeance.”

Across the 78 sentences in the lecture that Dylan spends describing Moby-Dick, even a cursory inspection reveals that more than a dozen of them appear to closely resemble lines from the SparkNotes site. And most of the key shared phrases in these passages (such as “Ahab’s lust for vengeance” in the above lines) do not appear in the novel Moby-Dick at all.

I reached out to Columbia, Dylan’s record label, to try to connect with Dylan or his management for comment, but as of publication time, I have not heard back.

Theft in the name of art is an ancient tradition, and Dylan has been a magpie since the 1960s. He has also frequently been open about his borrowings. In 2001, he even released an album titled “Love and Theft,” the quotation marks seeming to imply that the album title was itself taken from Eric Lott’s acclaimed history of racial appropriation, Love & Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class.

When he started out, Dylan absorbed classic tunes and obscure compositions alike from musicians he met, recording versions that would become more famous than anything by those who taught him the songs or even the original songwriters. His first album included two original numbers and 11 covers.

Yet in less than three years, he would learn to warp the Americana he collected into stupefyingly original work. Throwing everything from electric guitar and organ to tuba into the musical mix, he began crafting lyrics that combined machine-gun metaphor with motley casts of characters. Less likely to copy whole verses by then, his drive-by invocations of everything from the biblical Abraham to Verlaine and Rimbaud became more hit-and-run than kidnapping. The lyrics accumulated into chaotic, juggling poetry from a trickster willing to drop a ball sometimes. They worked even when they shouldn’t have.

In the past several years, Dylan seems to have expanded his appropriation. His 2004 memoir Chronicles: Volume One is filled with unacknowledged attributions. In more recent years, he has returned to recording covers, as many legends do. In Dylan’s case, his past three albums (five discs in all) have been composed of standards.

Dylan remains so reliant on appropriation that tracing his sourcing has become a cottage industry. For more than a decade, writer Scott Warmuth, an admiring Ahab in pursuit, has tracked Dylan lyrics and writings to an astonishing range of texts, from multiple sentences copied out of a New Orleans travel brochure to lifted phrases and imagery from former Black Flag frontman Henry Rollins. Warmuth dove into Dylan’s Nobel lecture last week, too, and found that the phrase “faith in a meaningful world” from the CliffsNotes description of All Quiet on the Western Front also shows up in Dylan’s talk (but not in the book).

Even many of the paintings Dylan produces as an artist are reproductions of well-known images, such as a photo from Henri Cartier-Bresson. For Dylan, recapitulation has replaced invention.

If the Moby-Dick portion of his Nobel lecture was indeed cribbed from SparkNotes, then what is the world to make of it? Perhaps the use of SparkNotes can be seen as a sendup of the prestige-prize economy. Either way, through Dylan’s Nobel lecture, SparkNotes material may well join Duchamp’s urinal and Andy Warhol’s fake Brillo pad boxes as a functional commodity now made immortal.

It’s worth mentioning that Dylan turned in his lecture just before the six-month deadline, ensuring that he would get paid. In the interest of settling any potential moral debt, I would encourage him to throw some of his $923,000 prize to whoever wrote the original version of the online summary.

In the meantime, I asked a few academics for their thoughts on whether Dylan had committed punishable literary theft. After reviewing the similarities, they gave mixed marks. Longtime Dylan fan and George Washington University English professor Dan Moshenberg told me no alarm bells went off for him while reviewing the passages. Gwynn Dujardin, an English professor from Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, had more issues with Dylan’s approach, noting the irony that “Dylan is cribbing [from] a contemporary publication that is under copyright instead of from Moby-Dick itself, which is in the public domain.” A final reviewer, Juan Martinez, a literature professor at Northwestern University, said, “If Dylan was in my class and he submitted an essay with these plagiarized bits, I’d fail him.”