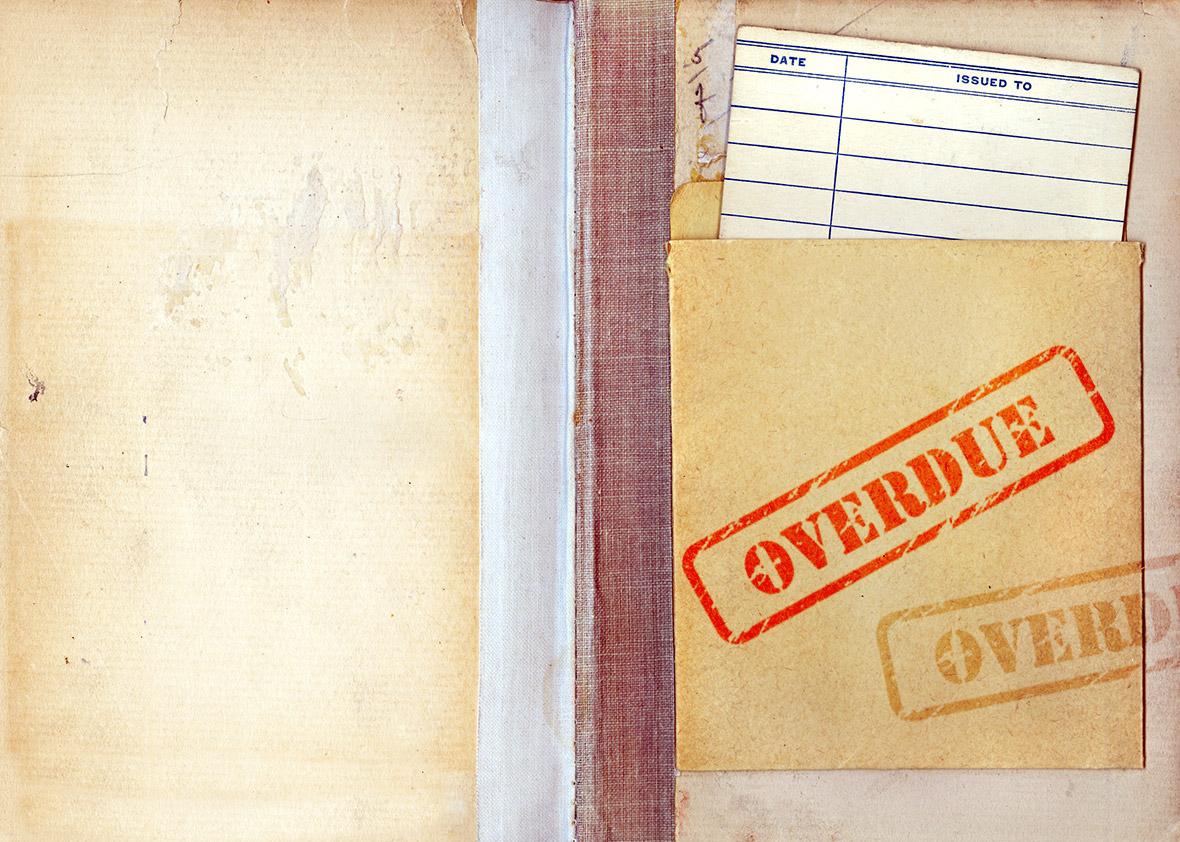

In 1906, a reporter for the Detroit Free Press described a scene that had become all too common at the city’s public libraries. A child hands an overdue book to a stern librarian perched behind a desk, and with a “sinister expression,” the librarian demands payment of a late fine. In some cases, the child grumbles and pays the penny or two. But in others—often at the city’s smaller, poorer library branches—the offender cannot pay, and his borrowing privileges are revoked. “Scarcely a day passes but it does not leave its record of tears and sighs and vain regrets in little hearts,” the reporter lamented.

More than a century later, similar dramas are still enacted in libraries across the country every day. In some districts, up to 35 percent of patrons have had their borrowing privileges revoked because of unpaid fines. Only these days, it’s librarians themselves who often lament what the Detroit reporter called “a tragedy enacted in this little court of equity.” Now some libraries are deciding that the money isn’t worth the hassle—not only that, but that fining patrons works against everything that public libraries ought to stand for.

Library fines in most places remain quaintly low, sometimes just 10 cents per day. But one user’s nominal is another’s exorbitant. If a child checks out 10 picture books, the kind of haul librarians love to encourage, and then his mother’s work schedule prevents her from returning them for a week past the due date, that’s $7. For middle-class patrons, that may feel like a slap on the wrist, or even a feel-good donation. For low-income users, however, it can be a prohibitively expensive penalty. With unpredictable costs hovering over each checkout, too many families decide it’s safer not to use the library at all. As one California mother told the New York Times last spring, “I try to explain to [my daughter], ‘Don’t take books out. It’s so expensive.’ ”

The good news is that librarians are noticing. Since 2010, districts in northern Illinois, Massachusetts, California, and Ohio—to name a few—have eliminated some or all late fines. Others are dramatically lowering penalties for late returns; last year, San Jose, California, halved daily fines to 25 cents and slashed the maximum payment per item to $5 from $20. The American Library Association issued a policy brief on services for the poor in 2012 whose first point was a vow to promote the removal of fees and fines. Is this “the end of overdue fines?” wondered the Public Library Association as the trend continued to gather steam a few years later.

In Columbus, Ohio, the library board announced in December that it would eliminate overdue fines starting on Jan. 1. The move came when the board realized that fines not only weren’t encouraging the timely return of materials—the little existing research on the topic suggests that small fees do not affect overdue rates—but that fines were actively working against the library’s very reason for existence. “We’ve shut off access to the library when one of our staunchest principles is trying to provide the widest access to materials that we can,” the system’s CEO, Patrick Losinski, said. “We just felt fines ultimately were counter to the overall purpose and vision of our library.” Instead of issuing daily fines, the library now blocks borrowing privileges for anyone with material more than 21 days late and charges replacement fees after 35 days that are refunded if the item is returned. It already offers a separate kids’ card, which allows children to borrow up to three books at a time and doesn’t charge overdue fines.

Late fines and replacement fees can have a huge cost to the communities libraries are meant to serve. Low-income children are dramatically less likely to have access to books at home or to spend time reading with their parents. A study conducted in the 1990s found that the average child in Beverly Hills, California, had four times as many books at home as the average child in Compton, California, had in her classroom library. (The average Compton kid, meanwhile, had 2.7 books at home.) More recent research has identified many poor neighborhoods as “book deserts,” with dramatically fewer reading resources than wealthier areas. “We’re disproportionately affecting the people we’re most interested in getting to the library,” said Meg DePriest, the author of a 2016 white paper recommending that Colorado libraries eliminate fines on children’s materials, “the people who can’t afford to buy books themselves.”

This is a conversation that has been percolating among librarians for several decades now. In her 2005 journal article on libraries and “socially excluded communities,” librarian Annette DeFaveri described a scenario in which a mother is charged $25 for a lost children’s book:

If the library does not charge for the damaged book, it loses about $25.00. … [But] it will cost the library more than $25.00 to convince this mother to return to the library. It will cost the library more than $25.00 to persuade this mother that the library is a welcoming community place willing to mount literacy programs aimed at her children, who will not benefit from regular library visits and programs. And when these children are adults, it will cost the library more than $25.00 to convince them that the library is a welcoming and supportive place for their children.

Eliminating fines, of course, also eliminates a revenue stream for a public institution that is often underfunded. The Columbus library system expects to forfeit between $500,000 and $600,000 this year. But that represents less than 1 percent of its overall budget. In fact, fines rarely make up a meaningful source of income for library systems.

In the summer of 2015, the 13 libraries of the High Plains Library District in northern Colorado decided to eliminate almost all their late fines. The district has now had about 18 months to assess what it means to survive only on fines from DVDs and lost-material fees. Naturally, revenue from fines and fees dropped, from about $180,000 in 2014 to an estimated $95,000 last year. But the system also got rid of most of its expensive credit-card machines and stopped leasing a change-counting machine that it had needed to process the avalanche of dimes and quarters. Executive director Janine Reid says the overall financial impact has been neutral.

Meanwhile, circulation rose, including a 16 percent rise within the children’s department. Staff members are happy, because they no longer spend time locked in awkward exchanges with patrons who are angry, distraught, or indignant about their overdue fines. And the fear that fines were the only thing between civilization and chaos has proved unfounded: 95 percent of materials are returned within a week of their due date.

Free public libraries are so interwoven into American life that it can be hard to appreciate their radical premise: Anyone in town can take home any book, for free. Overdue fines have always operated as a hedge on that communal trust, the nagging little stick that comes with the big, beautiful carrot. Fines imply that a library’s mission is not only to encourage reading but to perform a kind of moral instruction. But does it make sense for libraries to perform both of those jobs? “We’ve had 150 years to try to teach customers timeliness or responsibility, and I don’t know that that’s our greatest success story,” said Losinski, a few days after his library system abandoned late fees. Reid put it more simply when she explained the message she wanted residents of High Plains to take away: “We trust you.”