Alec Baldwin’s genius-level comic performance as 30 Rock’s Jack Donaghy was often the key to the show’s success. His expert timing, idiosyncratic phrasing, and insouciant arrogance made Donaghy a perfect foil for Tina Fey’s Liz Lemon. But none of this would have been possible without his voice, a quiet, low-pitched whisper. In an episode about Donaghy’s rivalry with Devon Banks, played by Will Arnett, Lemon famously dubbed Donaghy’s vocal style Talking Like This:

Baldwin and Arnett aren’t the only ones Talking Like This. It’s hard to watch a prestige television show or a major motion picture these days without encountering some version of men growling in a raspy low whisper. Just think about Tormund Giantsbane and Jon Snow sizing each other up. Or James Spader as Ultron. Or Andrew Lincoln’s Rick Grimes in The Walking Dead:

Just 25 years ago, Baldwin’s quiet growl was so uncommon that The Larry Sanders Show made a running gag of it, with Larry wrestling the upper hand from the much more attractive Baldwin by insulting his ability to project. Nowadays, Talking Like This is so ubiquitous that Will Arnett is about to launch a new children’s franchise based entirely on Batman’s harsh whisper. How did Talking Like This take over the male acting world?

I started by asking a performer who’s fascinated by the evolution of acting styles over time: voice-over, podcasting, stage, and screen veteran James Urbaniak. You’ve seen Urbaniak in the films of Hal Hartley or in television shows like Difficult People and Review. You’ve certainly heard his voice everywhere from commercials to Adventure Time and The Venture Brothers. Urbaniak heard the first hints of Talking Like This in the 1990s, when a trend overtook the world of voice-over performance, particularly in advertising: Damaged Voice. “I had to fake Damaged Voice—a throaty, cool, strained lower register similar to Baldwin’s—in auditions, because it didn’t come naturally to me,” he told me.

Urbaniak sees Talking Like This as a cross between Damaged Voice and a style he confesses is a personal obsession: Quiet Acting. “Every actor who has done film or TV has experienced a moment where you’re in a scene with another actor. You’re both on set. He’s two feet away from you, but he’s talking so quietly, you can’t actually hear him.” (In her memoir Bossypants, Tina Fey describes acting opposite Baldwin in similar terms.)

Quiet Acting long predates Talking Like This. You could almost think of it as Talking Like This’ father, in the same way that Donald Sutherland’s patrician whisper has been usurped by his son Kiefer’s low, determined growl. They’re both stylistic trends meant to give a sense of naturalism and urgency to a performance, but they’d both be impossible without technological innovations. Just as digital cameras and digital color correction allowed television cinematography to get darker than it’s ever been, so have supersensitive microphones and audio editing software made Talking Like This possible.

The introduction decades ago of body mics—tiny microphones close to actors’ mouths, instead of large boom mics pointed in an actor’s general direction—allowed actors to make Quiet Acting part of their repertoires, said Grammy-winning recording engineer and audio producer Zane Birdwell. “The human voice exists on an information spectrum that starts at around 200 hertz and goes up to about 3500 hertz,” Birdwell explained. “Through evolution, our ears have grown to pick up those frequencies.” According to Birdwell, when you talk into a microphone that is close to your mouth, the proximity effect makes your voice sound much different than it does in casual conversation. The microphone picks up “all the harmonics, overtones, and low bass frequencies” that don’t travel very well—and amplifies them.

Urbaniak likens the transformative impact of body mics on acting to how better microphone technology changed recorded singing. “Bing Crosby was one of the first popular singers who realized you didn’t have to worry about projecting,” Urbaniak said. “You could be subtle and naturalistic with phrasing, because your voice only had to carry to the microphone.”

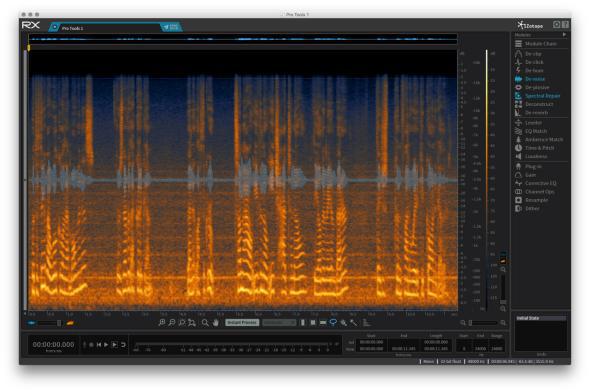

The use of body mics helps explain Quiet Acting, but it would take new innovations to get us to Talking Like This. Long after actors (and their voices) are off set, when a movie or TV show is in postproduction, audio engineers can now manipulate the individual frequencies within the human voice with ease and speed, thanks to the widespread use of digital audio, relatively new software plug-ins, and faster, cheaper, more powerful computers. In postproduction, audio engineers use something called frequency-specific compression to boost bass frequencies and minimize middle frequencies. Editing software can additionally dig into frequencies on the granular level. The RX 5 Audio Editor, made by the company iZotope, is a ubiquitous piece of software that creates, according to sound editor Eric Hirsch (The Get Down, Billions), “a visual representation of the sound you’re working with in all its frequencies in really micro detail.”

Screenshot from iZotope

In the image above, which Hirsch provided, the faint blue sound wave is the actor speaking in a somewhat noisy environment. The rest of the image shows all the frequencies within that sound clip. The brighter the color, the higher the volume. Using RX 5, sound editors can shift frequencies, lower the volume of frequencies, or edit them out entirely. Birdwell calls it “Photoshop for your ears.”

A frequent challenge comes when an actor talks so quietly that boosting his voice could cause a surge in the background noise. Let’s say you’re editing a scene between a classically trained actor and a total mumblepants. If you simply ramp up mumblepants’ volume, the background noise will suddenly surge. Hirsh explained a few of the techniques sound editors use to fix this problem. You can use audio editing software to find and eliminate the precise frequencies of background noise, though “if you do that too much,” he cautioned, “the voice will end up sounding thin.” Another solution is to boost the level of the noise in the rest of the scene so the noise level is constant.

A third option is to ask the actor to come in to do automated dialogue replacement, or ADR, a form of dubbing where actors re-record their lines in a booth during editing, synced up to their lip movements in the scene being edited. ADR has been around for a very long time and is a widespread practice. Thanks to the same advances in technology, it’s now cheaper and easier to do than ever before. Sound editors no longer have to splice and cut physical ribbons of tape to sync re-recorded lines. A show like Game of Thrones, in which actors are whisper-growling on outdoor locations with all sorts of wind and other noise, likely features far more ADR than you might realize. It’s not unheard of for an actor to completely re-record an entire performance. James Urbaniak told me that he did exactly this for Julie Taymor’s film Across the Universe. “You just try to match your vocal energy,” he explained. However, bad ADR is really noticeable. “ADR lines often stand out. They often have the more isolated sound of having been recorded in a booth.”

While ADR, frequency-specific compression, and spectrum shaping make Talking Like This sound much better than it used to, Hirsch stressed that actors are more likely to be influenced by watching the end product on the TVs than on the tech that makes it possible. “I’m not sure actors have any idea about what gets done to their voice in post,” he explained. “Talking Like This feels more like an acting virus. Technology has helped, but it’s a choice on the actor’s part.” The technology simply means that actors can now perform in a way that, “30 years ago, people would’ve said, ‘Cut, that’s not going to work.’ ”

Acting viruses always come and go. Urbaniak can rattle off many vocal trends over the years: from post-Brando mumbling, to Jane Fonda and Meredith Baxter speaking in hyperenunciated mid-Atlantic accents, to what he calls the gonzo performances of Nicolas Cage, John Turturro, and Crispin Glover in the 1980s. The specifics of male vocal trends, though, derive from our shifting ideas of masculinity. “When you’re whispering, you’re making a choice to restrain your expressiveness,” Urbaniak said. “This is very much in keeping with an old leading-man tradition of conveying strength through restraint.” John Wayne didn’t Talk Like This, but his voice still confined his expressiveness, which made him appear strong.

Today, just as the hypermasculine gym body has become ubiquitous in movies and TV, Talking Like This has become the gold standard of cinematic butchness. But it’s not without costs. There’s the literal cost; re-recording all of the dialogue in a film to get clean tracks a sound editor can manipulate takes a lot of time and money. But there’s also the cost in performance itself, as audio wizardry renders every actor’s voices the same. “Those same frequencies that get removed during compression are what make us sound like ourselves,” as Birdwell explained. Think of the difference between Michael Keaton’s Batman, who spoke in a harsh whisper but still sounded like Michael Keaton, and Christian Bale’s Batman, who sounds nothing like Christian Bale. Or a human being.

Eventually, the ubiquity of Talking Like This will pass. Technology and audience taste will change again and will intersect with a new vision of masculinity and new styles for actors to imitate. Tom Hardy’s vocal performance as Bane was an attempt to break with the expectation that a big-budget villain must Talk Like This, even if it was hilariously misconceived. Today, glimmers of an alternate vision of male performance emerge in less traditionally butch British exports like Benedict Cumberbatch and Tom Hiddleston, who are less restrained in their expressiveness yet remain sex symbols. Here’s hoping Hollywood rediscovers the fact that we all use a variety of voices, registers, and pitches throughout our day—and there’s nothing particularly natural or real about whispering in a monotone to begin with.