Think about the Kennedy assassination. What images comes to mind? Probably a pink pillbox hat, a limo surrounded by blue sky and green lawn, and JFK lurching grotesquely from silent bullets. What you are remembering is the 8 mm home movie that Dallas dress manufacturer Abraham Zapruder filmed at the moment that shots rang out in Dealey Plaza. Thanks to American pop culture’s 50 years of re-enactment and revisitation of the Zapruder film, the images from that film have, as scholar Marita Sturken argues, become our collective memory of the assassination.

American cultural obsession with the event appeared to reach its cinematic apotheosis with Oliver Stone’s 1991 blockbuster JFK, which not only meticulously re-created the Zapruder film in Dealey Plaza, but then in a climatic courtroom scene showed viewers the actual Zapruder footage, replaying the gruesome head shot over and over again (“back and to the left; back and to the left”). What was Stone’s purpose in using the Zapruder film? Convince viewers that a vast conspiracy was responsible for JFK’s death. Conspiracy theorizing has, of course, been the dominant narrative about the Kennedy assassination for more than 50 years. If we just revisit and re-enact the Zapruder film accurately enough, we might be able to finally figure out where the bullets were coming from.

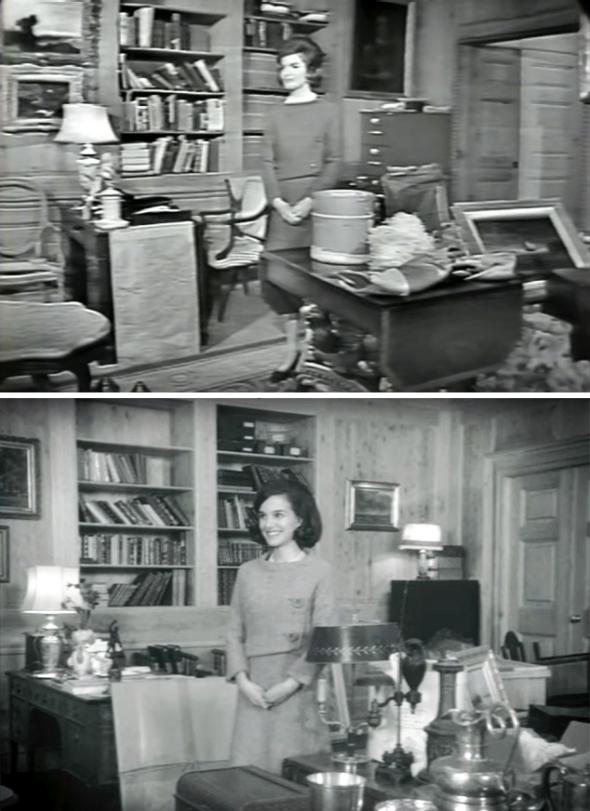

Pablo Larraín’s film Jackie, starring Natalie Portman as the first lady, suggests that some of the oxygen for the “who killed JFK” narrative has finally started to thin out. Like other Kennedy assassination narratives, Jackie gives us re-enactment. But its focus is not the Zapruder film. Instead Jackie dives into a Kennedy film that would be completely obscure to almost anyone under the age of 65. A Tour of the White House With Mrs. John F. Kennedy was a television sensation in 1962, carried commercial-free by CBS and NBC in prime time and then again four days later by ABC. Approximately 46 million households tuned in. Those huge numbers are surprising considering that Kennedy entertained no personal questions about herself or of her family’s life in the White House. Instead the first lady, who was visibly nervous, spent the one-hour program delivering art history lessons to an obsequious CBS reporter on the furnishings and objects she and her Fine Arts Committee had been amassing to “restore” the White House to suitable glory.

The “Jackie Show,” as it was dubbed at the time, might be a tough sell to modern TV audiences with its slow and stagey production, but for viewers in 1962, this was as close as they had gotten to their elusive, celebrity first lady. The new Kennedy White House on TV display suggested glamour and aristocratic sophistication. Jackie provided a vision of the United States as a country with as much history, culture, and refinement as any of its European allies. Dazzling state dinners were already a cultural fascination for many Americans who delighted in their president and first lady’s elegance and particularly in Jackie’s couture. (The Obama White House has echoed that Kennedy glamour.)

In one scene from the Jackie Show, the first lady takes viewers into the State Dining Room, extolling the gold flatware, President James Monroe’s centerpiece from France, and other opulent table decorations. But she makes a point of noting the simple glassware from West Virginia that she herself had procured. JFK’s 1960 primary win in that poor and predominantly Protestant state had been crucial to his securing the Democratic nomination. Jackie had campaigned vigorously for him there, and her nod to the state in the midst of all this luxuriousness perhaps signaled a touch of more traditional American simplicity and modesty.

Jackie structures its narrative around this TV memento to a time and place not yet called “Camelot,” flowing from the original in black and white to a meticulous full color re-enactment. At some point, Portman takes over the scene, but the actress has so precisely captured her character’s voice and mannerisms that it’s almost impossible to tell when “real” Jackie becomes the actress. In its obsession with verisimilitude, Jackie is reminiscent of the bravura opening of JFK, with its montage of actual footage shot in Dealey Plaza by Zapruder and others and Stone’s re-enactments.

Jackie returns to the TV special numerous times, and the movie’s poster features Jackie in the red suit she wore for the show, not the pink outfit and pillbox hat that have always served as iconic signifiers of the assassination. But the film is not about Jackie’s experience living in the White House. It’s about the assassination. Yet unlike most pop-culture treatments of the assassination, Jackie isn’t about who engineered the shooting, lone gunman Lee Harvey Oswald or a conspiracy. In avoiding the familiar images of the Zapruder film, the movie asks a different question: What impact did the shooting have on the first lady?

CBS and 20th Century Fox

In the film’s framing narrative, Life reporter Theodore White interviews Jackie (at her imperious command) for a feature in the magazine following the funeral. White confronts her with a recurring question: “What did the bullet sound like?” He doesn’t ask: “What direction did the bullet come from?”

Late in the movie, Jackie finally takes us to the moment of assassination in the limousine. But rather than give us the familiar Zapruder angle and the well-worn narrative, the film defamiliarizes the assassination with a bird’s eye view of the bloody horror. Viewers are right above the limo looking down at Kennedy’s bloody head in Jackie’s lap, giving us a similar vantage to Jackie’s. The scene, which is intercut with shots of Jackie at Arlington National Cemetery, gives us entrée into Jackie’s traumatized psyche and answers White’s question about the bullet’s emotional impact.

Compare this focus on a single, devastated woman with Stone’s JFK, which was haunted by a male-dominated baby boomer generational trauma: the country’s descent into cynical darkness and a disastrous war that would presumably never have happened under the idealistic and (in Stone’s questionable characterization) anti-establishment and pacifist Kennedy. “Don’t forget your dying king,” Kevin Costner tearfully tells jurors (and the audience) in the climactic courtroom scene without a trace of irony. Jackie also talks about kings: She tells journalist White that JFK liked listening to the soundtrack record of the Broadway musical Camelot and its story of idealistic King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. But the film complicates the Kennedy-Camelot myth by exploring and questioning how we create our historical narratives. Though the film participates in re-creating the splendors of Camelot in the Kennedy White House with recurring scenes of Jack and Jackie resplendent in glittery finery, along with its re-enactment of A Tour of the White House, Jackie encourages audiences to recognize where this vision of the Kennedy era came from—and why its creator felt compelled to manufacture it.

For many decades historians have shied away from engaging with the impact of the Kennedy assassination, leaving the subject to pop culture and conspiracy theorists. But just as Jackie has reframed the narrative, recent scholars and historians such as James L. Swanson, Alice L. George, and Larry Sabato provide fresh approaches to understanding this uniquely awful moment in American history and its ongoing legacy. Jackie’s biographer Barbara Leaming recently suggested that Jackie suffered a lifetime of post-traumatic stress disorder. Jackie dramatizes what that felt like for its protagonist. The nation also suffered a form of PTSD; that may be one reason we return to the scene of the trauma over and over. If we can stop obsessively asking where the bullet came from and start asking what the bullet sounded and felt like, we may have more enlightening stories and histories to tell.

Read more of Slate’s coverage of the Oscar race.