What makes these the best jokes of the year? We liked them, and we remembered them. Those were the two most important criteria. We culled them from a diverse range of media—books, TV, movies, cartoons, performance art—and tried to include ones that we felt had been overlooked or were particularly timely. Here they are in no particular order.

Tim Heidecker’s On Cinema endorsement of Donald Trump

Most of the pre-election comedy making fun of Donald Trump has not aged well. It feels feeble or arrogant, and in many cases the jokes reveal that we didn’t take the danger seriously. It also failed to achieve the political outcome I desired, so my brain wants to punish it by not laughing.

Comedian Tim Heidecker’s in-character endorsement of Trump is one of the only bits of pre-election satire that holds up and has somehow become funnier. Heidecker, playing his delusional self-involved alter ego on On Cinema, reads a marginally coherent prepared speech. He trips over pronunciation and can barely parse his own badly nested clauses but maintains a grave air of purpose: Trump “is the leadership of which we need to command our country back to a position of strength through leadership.”

Unlike other comics, Heidecker isn’t targeting Trump on an ethical or political level. Alec Baldwin’s Trump on SNL tries to make the candidate and his supporters seem repugnant. But Heidecker is ridiculing, rather than shaming, and his target is the aesthetics of Trumpism more than Trump himself. For Heidecker, Trump’s movement is a vortex of incoherence straining toward meaning but falling short even of platitude. It’s empowering to see Heidecker’s character inch toward this revelation as he speaks.

—Shon Arieh-Lerer, freelance video production associate

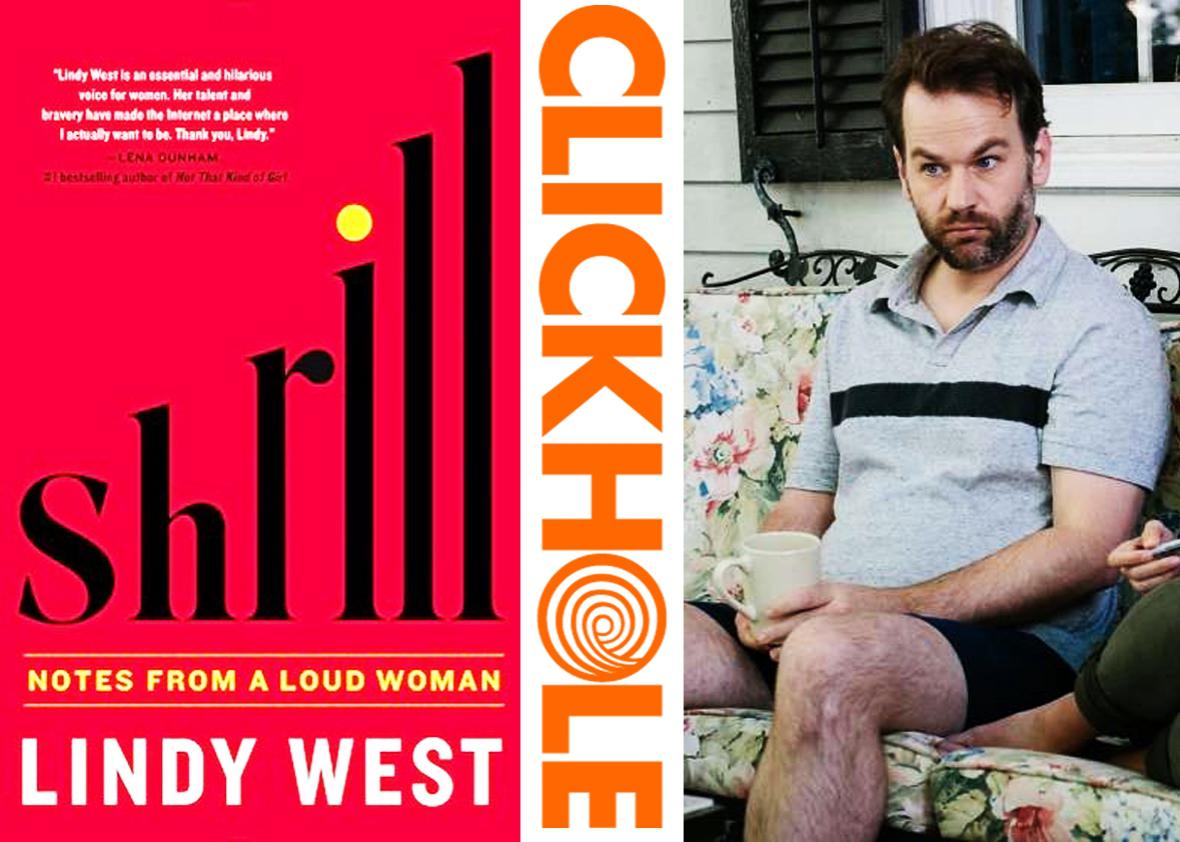

“Why is, ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’ the go-to small talk we make with children? … That’s like waking a dog up with an air horn and telling it that it’s president now.”—Shrill, by Lindy West

The entirety of Lindy West’s memoir Shrill is hilarious, but I especially loved her (trenchant!) observation that asking kids to map out their most important life decisions—and engage with existential questions about their place in the world—as a form of banter is pretty nuts. Also, the juxtaposition in a single image of dogs, airhorns, and the presidency is brilliant.

—Katy Waldman, words correspondent

The father’s return in Toni Erdmann

Sony Pictures Classics

The best gag in any movie this year takes place in Maren Ade’s caustic comedy Toni Erdmann, after the high-powered Bucharest businesswoman played by Sandra Hüller sends her irritating visiting father back to Germany. Watching the film I assumed, though the movie had already surprised me quite a few times, that I could reasonably expect the father’s eventual return, but the timing and manner of his reappearance is so surprising, outrageous, and hilarious that I’ll remember that movie-going moment the rest of my life. You may scream.

—Dan Kois, staff writer and editor

“When a small bucket fits inside a larger bucket, it’s two buckets. When the larger bucket fits inside the smaller bucket, it’s one bucket.” —The fourth item in ClickHole’s “6 Lies About Buckets You Can Tell Your Dim-Witted Aunt This Thanksgiving”

This joke is a virtuosic demonstration of the many ways in which a logical statement can be totally free of information. In the first sentence we have a tautology implying another tautology. In the second, we have a contradiction implying another contradiction. What makes it so funny is that it purports to be communicating some kind of real conceptual distinction while so obviously being a total logical dud of a statement. In order to take it seriously as a fact, the hypothetical “dim-witted aunt” to whom you’re telling it must be a being of infinite and perfect stupidity, just like Anselm’s God is a being of infinite and perfect existence. Imagining such an aunt is, for me, the comedy equivalent of a religious vision.

—Arieh-Lerer

“The Best Time I Pretended I Hadn’t Heard of Slavoj Zizek” —Rosa Lyster, the Hairpin

If the goal of satire is to make people feel bad for violating norms, the goal of trolling is to make people feel bad for enforcing them. This year, a big troll with a standing army of little trolls became president. But there is such a thing as ethical—or at least ethically neutral—trolling, and it can be funny, and Rosa Lyster modeled it superbly in a piece she wrote for the Hairpin in July, called “The Best Time I Pretended I Hadn’t Heard of Slavoj Zizek.” The author, who is a graduate student in South Africa, likes to drive “Marxist bros” crazy by pretending she has never heard of the philosopher Slavoj Zizek, a universal idol of Marxist bros. Lyster feigns ignorance of other cultural reference points, too, varying the reference point to generate maximum confusion in her target. Among the rules for the “Zizek game,” the most important is not to cause any actual harm. This is my kind of comedy: humane and foolish, far from the animus of the Pepe the Frogs or the smugness of liberal late-night humor.

—interactives editor Andrew Kahn

The fake reported segment on a “trans-racial” kid in Donald Glover’s Atlanta

Atlanta’s seventh episode (“B.A.N.”) is hard to explain, but it features rapper Paper Boi’s appearance on a parody of a TV newsmagazine called Montague. Paper Boi clumsily discusses Caitlyn Jenner with a trans-rights advocate, and then comes a fictional reported segment on a “trans-racial” black teenager who believed himself to be, in his heart of hearts, a 35-year-old white man. The segment itself is hilarious, down to the B-roll footage of the kid walking around in the dad jeans and New Balances of a much different man, but my favorite part is when he comes back, after his “reassignment” surgery, with a mop top of blond hair that inspires Paper Boi, with the delivery that earned him a spot in Slate’s best characters of the year roundup, to mock him as a “fake Ellen DeGeneres … a Fellen DeGeneres.” When he then finds out that the trans-racial kid doesn’t support trans or gay rights, and cracks up, fist to his mouth, it’s a gesture that rivals the Wee Bay GIF in its pure, exuberant expressiveness.

—Heather Schwedel, copy editor

Dankyougene

New Yorker cartoons aren’t known for being laugh-out-loud hilarious, but one of them this year had me doubled over, helpless to contain my guffaws. Ben Schwartz’s single-panel tribute to Gene Wilder, which featured three Oompa Loompas singing, “Oompa loompa doopity dankyougene… ” was—inadvertently—one of the funniest jokes of the year. The contrast between the cartoon’s self-serious tone and the fact that it didn’t make sense on any level continues to provide me with deep joy. As a bonus, “dankyougene” has become an all-purpose way of expression mildly ironic gratitude in emails, tweets, and IMs. To Mr. Schwartz, who good-naturedly chalked up the cartoon to “a swing and a miss,” I offer a hearty dankyougene.

—L.V. Anderson, staff writer

Sam Lavigne’s Online Shopping Center digital performance art

If you talked to anyone in the last year who hopes to make some money in tech, you probably heard the term “machine learning.” It refers to the subfield of computer science in which programmers teach machines to recognize patterns independently, including patterns of human behavior. Those patterns can then be fed to algorithms that set the price of an Uber, the interest rate on a mortgage, or the length of a jail sentence.

This summer, with Dada flair, the digital artist Sam Lavigne made the worst possible machine-learning-powered algorithm and used it on himself. Lavigne “trained” an algorithm to recognize two—and only two—possible brain states: thinking about death and shopping online. (There’s a long and living tradition of trying to read minds with this technology, dating back to research on criminals in the ’50s.) Lavigne then went to bed wearing the EEG and let it execute his desires. Whenever the program recognized a “shopping” brain state, it put a random item in Lavigne’s Amazon shopping cart. After a few nights, the cart was filled with used guitars, crappy toys, and clothing for all genders and sizes of people. He filmed the whole thing.

Lavigne’s piece is an act of satire, and its brilliance has several facets. First, it is always satisfying to see a complicated and pointless machine, like those imagined and built by Rube Goldberg and Jean Tinguely. Second, the piece clearly demonstrates that, though an engineer can teach a machine to sort empirical data into categories, nothing guarantees that those categories will be remotely appropriate. The categories Lavigne chose (thinking about death and shopping) are woefully insufficient, reflecting not the versatility of an actual brain but the monotony of a capitalist dystopia. Third, the program does intentionally what a bad algorithm does unintentionally: It shapes reality to meet its assumptions. When Lavigne is sleeping, he is manifestly not shopping—but because his brain looks like it once did when he was shopping, the program makes him shop.

This delusional, obsequious machine—a robot clown—was my favorite joke of 2016.

—Kahn

“It’s like when someone says something that sounds funny, but isn’t funny.” —Mike Birbiglia’s Don’t Think Twice

The best joke about jokes I heard this year came in Birbiglia’s ode to improv comedy and frustrated careerism Don’t Think Twice. Watching their ascendant teammate perform in the SNL-esque “Weekend Live,” the members of the improv troupe the Commune struggle with their contradictory impulses to feel proud of their friend while still dumping on late-night middlebrow trash. Finally Allison (Kate Micucci) comes up with the right description: “It’s like when someone says something that sounds funny, but isn’t funny.”

—Kois

The year 2016

You know those jokes that take a sensitive, depressing, and/or scary topic and twist it into absurdity and hilarity to the point where you’re both LOL’ing but also cringing because it’s too real? Like Key & Peele’s “Negrotown” or Amy Schumer’s “12 Angry Men” sketch? Or, shall we say, the 2006 satire Idiocracy? Well, that was 2016, a number that has become a meme in itself—it dared us to keep laughing at it as the days went by, throwing increasingly more horrible things our way. We did not begin to take it seriously as the worst calendar year in recent memory until it was too late, and by then, well—the joke was on us.

—Aisha Harris, staff writer

Tatiana Navka and Andrei Burkovsky’s Holocaust-themed figure skating routine

This was not a joke. This happened in real life, on a Russian Dancing With the Stars–like show called Ice Age. In a supposed homage to the film Life Is Beautiful, two dancers dressed in concentration camp uniforms with yellow “Jude” stars gracefully pantomimed running away from a Nazi guard dog and getting mowed down by a machine gun (with sound effects). It’s an earnest real-life version of Mel Brooks’ Hitler on Ice. And as a bonus irony: The female dancer, Tatiana Navka, is the wife of one of Putin’s spokesmen.

As a work of art created by two Russian ice skaters, this routine is tasteless and demoralizing kitsch. As a work of art created by the universe that had just brought us the Trump election, it is a masterpiece of staggering ironic genius and poetic injustice—a sublime “fuck you” to history, humanity, and the reality of human suffering. Comedy is tragedy plus ice.

—Arieh-Lerer