Fair Lawn, New Jersey, late ’50s. I must have been 9 or 10 when my Uncle Al surprised my cousin Jack and me by announcing his intention to take us to a midnight showing of Diabolique, the French thriller. The choice seemed odd, since Al, a burly luncheonette operator from Passaic, wasn’t the type you’d expect to harbor a taste for French cinema. Then again, it was no secret that an intermittently active strain of sadism ran in Al’s branch of the family. I guess he didn’t want to miss out on a rare opportunity to watch the kids squirm.

Shot in cadaverish black and white, Diabolique is about these two hot babes, the wife and mistress of a cruel boarding school headmaster, who conspire together to murder their tormentor. They drug him, drown him in the bathtub, and dump his body in the swimming pool. When the pool is drained, though, there’s no corpse to be found. The two women freak out for the rest of the movie. At the end, there’s a scene where the (supposedly) murdered headmaster inexplicably rises out of the bathtub with only the whites of his eyes showing. That’s when I started screaming. Jack, his body quaking from head to toe, slid off his seat and ended up on the sticky theater floor in tears. When we got home, Uncle Al, who’d had a merry old time, had to endure a tongue-lashing from my aunt for permanently damaging our heretofore immaculate sensibilities. We both had nightmares for weeks.

But movie terror is seriously addictive. As soon as we were sufficiently recovered, we started taking the bus to the HyWay Theater every Saturday afternoon to see the horror double feature. At 50 cents plus the price of the popcorn (or a bit more if you wanted a box of the race-regressive Chocolate Babies), it was a bargain.

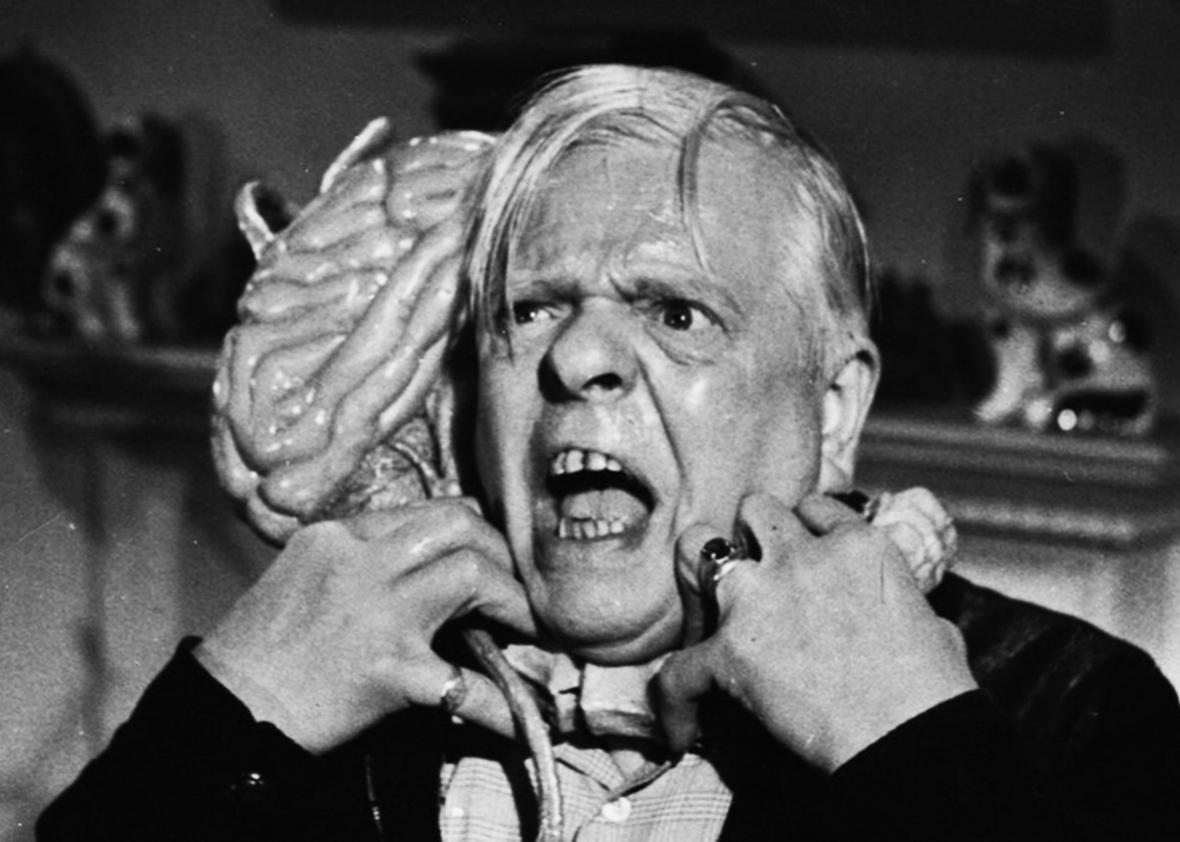

Amalgamated Productions

Some programmer had paired The Brain Eaters with Fiend Without a Face, having noticed that the heavies in both pictures are brain-shaped. In Fiend, a mad scientist with telekinetic powers generates invisible creatures that extract the brains and spinal columns from their victims. But a fiend is what a fiend eats: The creatures ultimately materialize in the form of a tadpole-ish brain–and–spinal column combo. They skate around the floor, fling themselves at people’s faces, and whip their tails around their necks. Luckily, the creatures aren’t all that hard to kill: When struck with a bullet, they pop open like a gore-filled piñata. This was my first yuckfest.

In the second feature, The Brain Eaters, little brain-shaped parasites attach themselves to the back of the human victim’s neck, plug in a couple of tentacles, and turn the host into a helpless slave (read: commie dupe). In a Morlockian twist, the creatures are not extraterrestrials, but intra: Their mole car has drilled up to the surface from their hive deep in the Earth’s substratum. The humans soon find out that the brain eaters have no need for a violent invasion: “We can scatter quietly like seeds in the wind,” says the head honcho. Oh yeah? Well, scatter this, Nikita: The humans have a secret weapon: high-voltage power lines, Hollywood’s go-to weapon for quick monster disposal.

A note: When I saw this picture, I thought the story was awfully reminiscent of Robert Heinlein’s novel, The Puppet Masters. So did Heinlein. He sued Roger Corman’s ass and won.

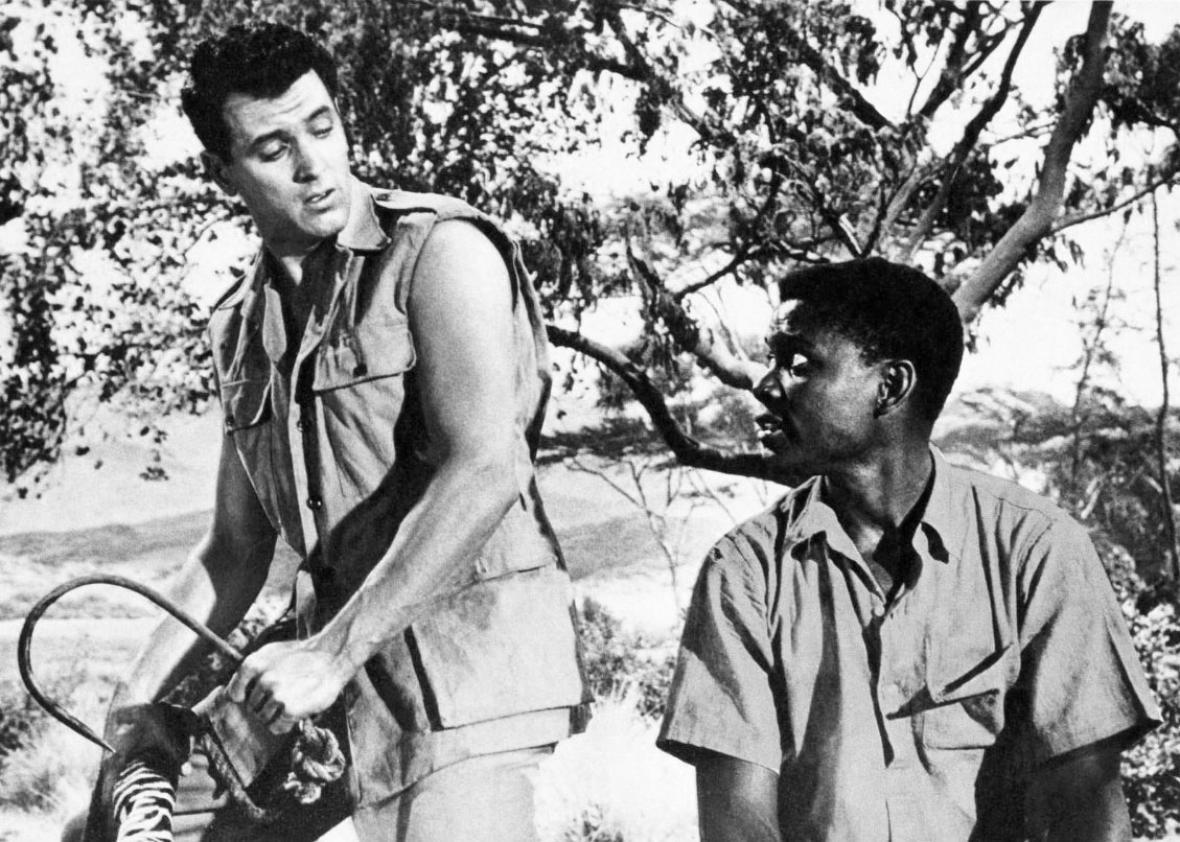

One weekend we noticed a poster for a grown-up film playing in East Paterson called Something of Value. The poster showed Rock Hudson in a safari jacket being threatened by a black man wielding an enormous machete. Co-starring were Sidney Poitier and pale, luscious Dana Wynter. We were already familiar with Dana as the chick who succumbed to the pod people in Invasion of the Body Snatchers. In all her roles, Wynter had at least one telekinetic power: She could raise a teen penis by just appearing on the screen. Admission was restricted to 12 and older, but we managed to sneak by the box office.

Paramount

In this topical melodrama based on Robert Ruark’s best-seller, Rock and Sidney are childhood friends, brought up together on a farm in Kenya. A few years later, Sidney joins the Mau Mau terror organization and starts slicing up white people in their beds. To this day, I still wish I could unsee these scenes. But more confusing and frightening was the idea that your best pal could suddenly decide to slice your head off with a machete. It was a first look at real-life horror. In a small way, seeing this picture changed my life: I switched from Chocolate Babies to Milk Duds and never looked back.

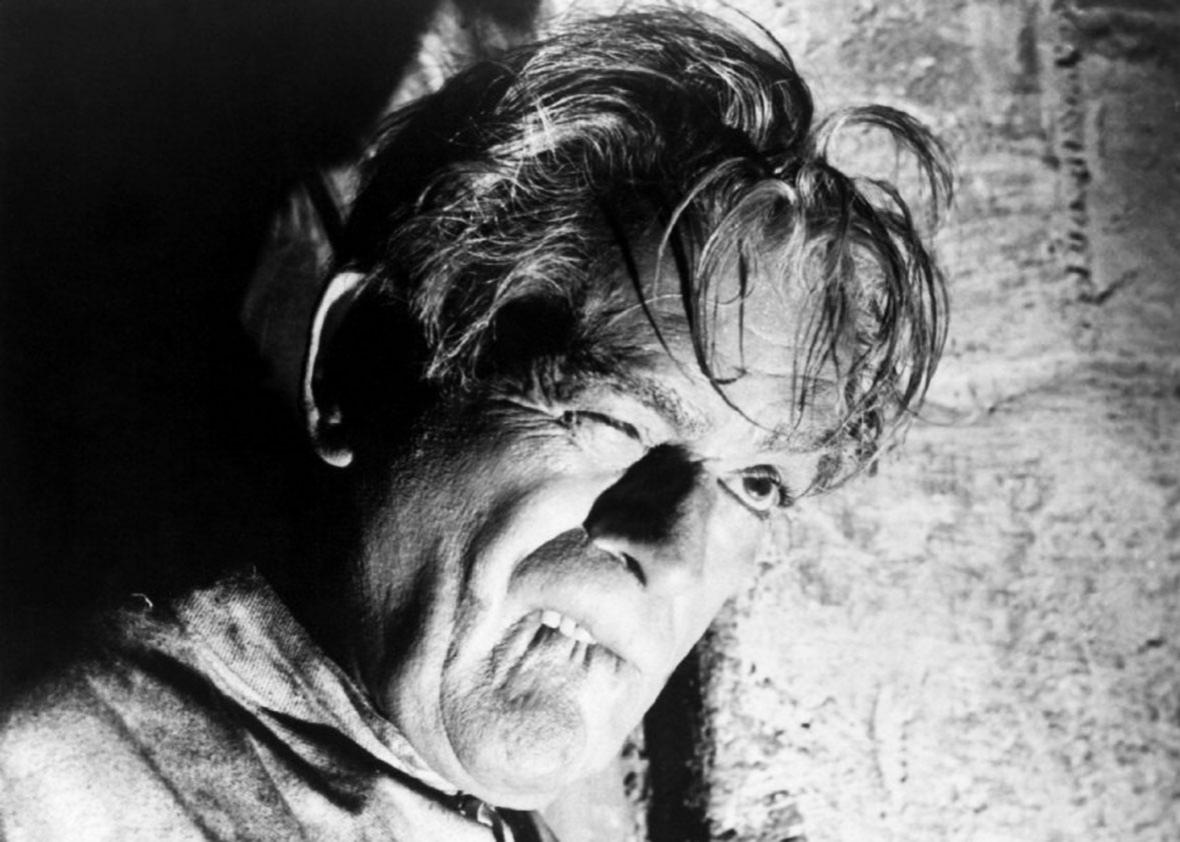

A week later, we were back at the HyWay Theater. In The Haunted Strangler, a man named Styles is hung for a series of Ripperish murders. The victims were the usual array of Victorian-age prostitutes and music-hall sluts. Twenty years later, a writer (Boris Karloff) is trying to prove that Styles was wrongly convicted. His investigation leads him to suspect that the real Haymarket Strangler was the surgeon who performed the autopsy on the hanged man. After exhuming Styles’ corpse, Karloff finds that the surgeon’s scalpel has been buried alongside the body.

Amalgamated Productions

As soon as the courtly old gent picks up the infernal scalpel, he assumes the appearance of a hideously deformed fiend. OMG!—it was Karloff himself (that is, his grotesque alter ego) who did the original murders. Oedipus-like, he has unmasked himself as the killer. Karloff, then in his 70s, pulls off this terrifying effect with minimal makeup by simply screwing up his mouth, mussing his hair, and clamping his left arm to his chest. His pent-up, palsied mien suggests sexual fear and repression, a powerful image to drop on an audience of pubescent boys. He looked as if all the things they said would happen if you obsessively masturbated were happening to him.

Earlier, Karloff had interviewed the bawdy showgirls at the local cabaret, “The Judas Hole,” the strangler/slasher’s favorite hang. Cora, the bootylicious star attraction, sings this number:

Oh Cora, Cora

All the boys adore-a

She’ll play the part

She’ll give her heart

And maybe a little bit more-a

One more-a thing: This was the first film I saw that featured a public hanging scene, the kind where the old cockney crone in the street and the whore leaning on the windowsill are having the time of their lives, cackling heartily as the hangman tightens the noose around the prisoner’s neck and drops him through the gallows floor. That’s entertainment, I guess, for the same reason Jack and I were sitting bug-eyed in the third row.

In the late ’50s, Screen Gems released a large cache of Universal horror films for broadcast on television, to be presented under the name Shock Theater. The concept required a campy crypt keeper to introduce the scratchy old films to a young audience. In Los Angeles, the hostess was Vampira. Cleveland had Ghoulardi. The New York edition was hosted by Zacherley, the “cool ghoul,” a gaunt gent in white makeup with dark shadow smeared on his eyes and cheekbones, and dressed in a long undertaker’s coat. Zach (actually actor John Zacherle) lived in a mausoleum with his never-seen wife, Isobel, and his son, Gasport, a thing in a burlap bag that hangs on the wall. The no-budget set and Zach’s throwaway improvisations gave the show a kind of illegal, pornographic feel, as if it were being broadcast from a barge off the Tijuana coast.

With spooky electronic music playing in the background (Varese?), Zach would concoct some inane parallel plot involving Isobel, Gasport, and any number of dime-store props like dolls and rubber chickens. While the film was playing—The Black Cat or The Mummy’s Ghost or Son of Dracula—Zach would insert himself into the action. For example, if a pair of resurrection men were standing in the boneyard at night making nefarious plans, they’d cut to Zach leaning on a headstone, urging them on with that lunatic grin on his face. It was the lowest of low comedy, aimed at snickering, Frito-scarfing 10-to-14-year-olds. Zach became so popular, he even had a hit single, “Dinner With Drac.”

Inspired by the success of Shock Theater, sci-fi/horror superfan Forrest J. Ackerman created the magazine Famous Monsters of Filmland in 1958. I was a subscriber. There were articles about the actors, special-effects techniques, and gory makeup secrets. Also lots of film stills of hideous ghouls threatening gorgeous starlets in diaphanous nightwear. But, strangely, the more insider secrets I learned, the less interested I became in the films themselves. Or perhaps I was just growing out of it. Either way, the magic was gone, and horror films joined the list of stuff I was now embarrassed to have embraced, like electric football, Jerry Lewis, and prank phone calls.

By 1961, my family had moved out of Bergen County. But one Saturday, back for a visit, cousin Jack and I took in one last double feature: the ghastly combination of Roger Corman’s Pit and the Pendulum and Mario Bava’s Black Sunday. Both pictures featured Barbara Steele, a cult star of the ’60s and ’70s and the main crush of necrophiles the world over. Pit was one of several Poe-inspired films intended to imitate the look and feel of the new horror line then being produced at Hammer Films in England. Corman’s pictures approximated the same dank, greenish color and lush-looking set design.

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc.

The original story, like a lot of Poe, is mostly atmosphere, so the screenwriter, Richard Matheson, had to mine other material from the Poe canon to come up with a plot. I’ll spare you most of the sad details. Suffice to say that Vincent Price flounces around a sepulchral Spanish castle with a bad case of post-traumatic stress disorder because he thinks he accidentally buried his wife, Elizabeth, alive. Meanwhile, there are hints that Liz is still kicking (ethereal harpsichord music, etc.). Eventually, Price goes totally bughouse and tries to slice someone in half with a massive, swinging Cuisinart blade that he maintains in the cellar. It’s an incredible relief when Barbara Steele shows up, but just then the whole cast leaps into a flaming pit and the picture’s over.

Mario Bava’s awesome Black Sunday opens with flames at night and silhouettes of naked trees against the fog. Beautiful Asa Vajda (again Barbara Steele) is about to be burned at the stake for sucking the blood of the good people of Moldavia, fornicating with the demon Javuto, and general witchery. But first, the Inquisitor, Asa’s own brother, orders that she be branded with the sign of the devil.

Shining with sweat, the beefy, hooded enforcers remove the branding iron from the flames and press it into Asa’s white flesh. She screams in pain. Now defiant, dark eyes blazing, she declares her immortality and vows to bring Satan’s curse down upon her brother and all the generations that will follow. The enforcers lift a heavy iron mask from the ground and we see the sharp spikes protruding from the inner side. They carefully align the mask with Asa’s face. The Captain picks up a huge wooden hammer, yanks it back, and whack, he pounds the thing home. Jack and I bolted at the same time and charged up the aisle, popcorn and Milk Duds flying, and then we’re out the door, running down the sunlit street to catch the next bus home.

I stayed away from horror pics until the ’80s when, as a grown-ass adult, I became fascinated with the films of David Cronenberg: The Brood, Scanners, Videodrome, Dead Ringers, The Fly, Existenz. Critics have called his stuff “body horror.” But, really, as we age, it’s all body horror. The extraordinary facts of life—eating, excreting, sex, violence, disease, all our mysterious compulsions—these are the elements that constitute the plot of the scariest movie ever. Kids start to sense this early on. Especially by the light of the full moon, when we first saw poor Lon Chaney Jr. standing on the forest path, helpless to prevent his transformation into a drooling, feral animal. Ah-ooooooooo!