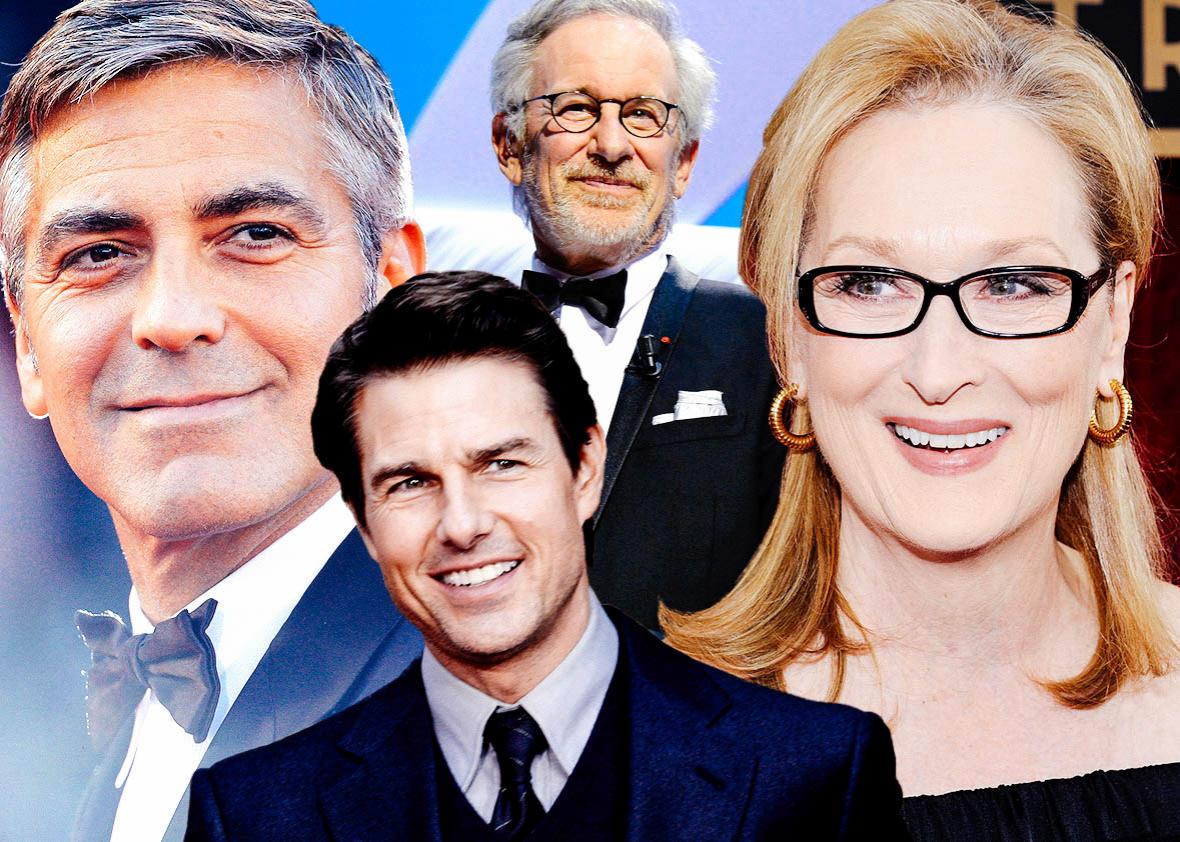

In 1975, five agents from William Morris decided to start their own talent agency. Led by the legendary (and legendarily brash) Michael Ovitz, Creative Artists Agency went on to become the most important shop in Hollywood, representing the upper echelons of the A-list: Tom Cruise, Steven Spielberg, George Clooney, Meryl Streep.

James Andrew Miller’s new oral history, Powerhouse: The Untold Story of Hollywood’s Creative Artists Agency, is both a narrative of CAA and a broader story about the ways in which Hollywood has changed over the decades since 1975. Following his earlier accounts (co-written with Tom Shales) of Saturday Night Live and ESPN, Miller interviewed many stars, as well as Ovitz and his onetime friend and partner Ron Meyer.

During the course of our phone conversation, which has been edited and condensed for clarity, Miller discussed the skill it takes to manage celebrities, the surprising depth of Sylvester Stallone and Tom Cruise, and why the era of movie stars may be coming to an end.

Isaac Chotiner: What made you want to write a book about the Creative Artists Agency?

James Andrew Miller: Saturday Night Live and ESPN, [the subjects of] my two previous books, were both born in the ’70s, and are still very much with us and are hugely successful. They also both enjoy worldwide recognition: You see those initials, SNL or ESPN, and you know them right away. CAA was also born in the ’70s, but it is less known. One of the things I have continually heard from people is that they had no idea that CAA was such a part of their lives. Not only did they not know the initials, but they didn’t realize that the Tom Cruise movie or the Meryl Streep movie, Game of Thrones, Walking Dead, Empire, Katy Perry, Bruce Springsteen, One Direction, were CAA. Even when you walk into a Chipotle, CAA advises and does marketing for Chipotle. And now there’s CAA sports with J.J. Watt or Dwyane Wade. That was a different challenge: to reveal the DNA of a brand that people weren’t all that familiar with.

So how did CAA change Hollywood?

One of Ovitz’s favorite words is disruption, and beginning in the late ’70s, they disrupted the customary equation that talent agencies had used in Hollywood for decades. I can give you a couple examples. Just the idea—it sounds like a simple thing—that when studios would make an offer to an actress or an actor, they would deliver the script to the agent and the actor or actress would read it and say yes or no. When that happened with CAA, they wouldn’t let a no answer go back. What they did instead was say, OK, we have this offer out for Paul Newman. He doesn’t want to do it. Who else here has a male client who can read this script? So instead the call back would be, OK, Paul Newman said no, but here is Robert Redford or Dustin Hoffman or countless others. What that shows is another way in which they changed things, which was transparency. There was a horizontal nature to CAA as it evolved, which was very, very important in terms of transmitting knowledge. The traditional agency model had been very siloed. And in fact some agencies are still like that, but when you have that kind of communication between agents, and everyone is responsible for conveying critical information, then you start to have a different kind of power behind you. Knowledge is power.

That horizontal aspect also shows up in CAA’s use of “packaging,” which basically means getting different CAA clients slotted into a bunch of roles in any given movie or show.

CAA didn’t invent packaging, but they took it to new levels, and did it more often and with greater results than anyone had done beforehand. Packaging is getting key elements of a movie or television show together so you basically control that piece of intellectual property. So much of what we saw in the late ’70s and ’80s and ’90s and even still to this day, coming out of CAA, was this idea that, wait a minute, it’s a CAA script in terms of a CAA client had written that script. They didn’t start taking it out to other agencies and trying to find out who could direct it. They were going to find a director inside CAA. They were going to find the actor or actress inside CAA. And as a result, before the other agencies could get their hands on it, you basically had a CAA package. What that also meant, particularly in the ’80s and early ’90s, because it was a seller’s market, was the ability for CAA to call up studios and say, Look, we have Tom Cruise and Dustin Hoffman and Barry Levinson. Do you want this? Ghostbusters and Tootsie and the list goes on and on of projects with CAA clients in pivotal roles. Sometimes it was already cast before it got to the studio.

What was it about Ovitz in particular that was so remarkable and also made him so difficult to work with?

Let’s start with the fact that those two things often coincide, right?

Look, I am not saying that Michael Ovitz was Steve Jobs, but one of the reasons that Steve Jobs was such an amazing character was because he was a visionary and people found him cantankerous and difficult to get along with. Sometimes it wasn’t easy to be around him. One of the things that Ovitz and Ron Meyer and Bill Haber did very, very well at CAA was develop new rules for the way they were going to operate their business. Sometimes those new rules were exciting to people inside their agency and sometimes exciting to the people they dealt with at studios, but sometimes they weren’t. When you become that powerful and throw your weight around, the inevitable results are not shocking: There is resentment and bitterness. As a result, the town first marveled at CAA’s success; but then a lot of people became, especially with Ovitz, resentful of the power.

Why was Ovitz a great agent? You have a section on David Letterman, who essentially says that Ovitz rescued him, in terms of his career and even emotionally.

There is a great irony: In the ’80s and ’90s, before Ovitz and Meyer and Haber left, the client list was huge. It was the varsity. They were in the deep end of the pool. They had great clients. And yet at the same time, what Letterman talks about, what Scorsese talks about, in the case of Ovitz, was that he had this ability to make you think you were the only person in the room. Now, Meyer, who had an unbelievable client list, also had that ability, but it was different; it was an emotional connection. I had client after client say they thought of him like family. But with Ovitz it was this knowledge that he was the toughest guy on the block and he was going to do everything that needed to be done in order to prevail.

I think one of the things that enabled Ovitz to accomplish what he did between 1975 and 1995 that was great for his clients and CAA but bad for him personally was that he was constitutionally incapable of being satisfied or even taking a moment to smell the proverbial roses. If you aren’t Spielberg, but you are another client, you are glad this guy is not going to take a week off and celebrate some deal he made. The next minute he will be onto your case. He was insatiable in terms of his drive and the need to keep doing business.

Who among the stars you talked to did you find particularly surprising and insightful? For me it was Stallone.

I am right with you with Stallone. With all due respect, I have been asked that question before and Stallone is about my first answer. It was really shocking, not because I have stereotyped him as Rocky, but I had no idea he could be so raw and emotional, particularly on the record. Whoopi Goldberg was fantastic. Cher was crazy funny and very clever and wickedly honest. Again, there is a tendency to kind of think, Oh, actors, actresses, was it really interesting talking to them? Well they are people too.

I thought Tom Cruise—look, he got to CAA when he was 19 and he is still there. I think one of the things I found with Cruise was his ability to talk about his interest in moviemaking, and how much he cared about and loved the movies. It sounds kind of pro forma, but it really wasn’t. He was very expansive on that subject and very clever about it.

Your book has an interesting comment from Ovitz where he says that, essentially, when he was managing Cruise, the actor never had any of the Scientology driven PR disasters he has had in recent years.

[Laughs.] It’s one of those Ovitzian statements that can be studied for quite some time because some people took it as a shot at the current leadership, and some people just talked about it as Ovitz taking a bow for something that wasn’t necessarily on his watch. I will say this though: CAA gave a wedding reception for Tom and Nicole Kidman, and Ovitz invited David Miscavige, the head of the Church of Scientology. He put him at the head table. I think Ovitz probably deserves a pretty big bow on handling that relationship. He decided that he was going to do what he felt Tom wanted.

Hollywood is obviously different now. Broadly speaking, movie stars count for less now than they did in Ovitz’s era. How do you think this will change places like CAA going forward?

The equation of fewer studios, and fewer movies being made, particularly of the type we used to see in the ’60s and ’70s and ’80s and even before that, is important context to keep in mind. I also think it speaks directly to why you see CAA expanding the way it did under Ovitz and now. One of the things I was able to report in the book was that in 2015, CAA Sports, which just began in 2006, was the No. 1 revenue generator in the agency. So you have sports making more money than television or movies or music. That is a significant paradigm shift.

And that shows no signs of changing right? Isn’t the conventional wisdom that because of the value of live events, sports will become even more valuable in the current media environment?

I think so. One of the things we have come to realize more and more in the last decade is the value of live sports, in part because you don’t really know whether even your biggest hit show will be around in four or five years. But you know people are going to care about the Rose Bowl, and watch Sunday Night Football or Monday Night Football and the NCAA Tournament. That kind of stability, for a network or media company, is important.