De La Soul’s Stakes Is High was the first album I ever heard that opened with people talking about another album. “When I first heard Criminal Minded” is the LP’s opening line, six words patched together from four different voices captured on the same answering-machine tape followed by a barrage of memories that lasts over half a minute. The object of reminiscence, of course, is Boogie Down Productions’ 1987 debut Criminal Minded, an album that changed hip-hop with its earthy, DIY aesthetics and introduction of a 21-year-old KRS-One, one of the greatest vocal talents the music had ever heard. At the time of Stakes Is High’s release, Criminal Minded was 9 years old but already felt ancient, like some sacred inheritance.

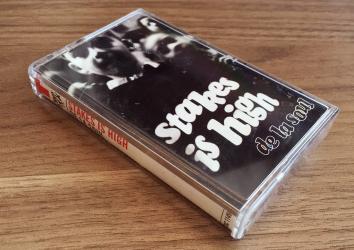

Stakes Is High turned 20 years old earlier this month, an anniversary that, with few exceptions, went mostly unmarked by the lavish fanfare that in recent years has met the emerald anniversaries of The Chronic, Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), Illmatic, Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik, Ready to Die, The Infamous, or Reasonable Doubt. This isn’t surprising: Most people would probably rank Stakes Is High as the fourth-best album in De La Soul’s catalogue, behind the three that came before it: 1989’s 3 Feet High and Rising, 1991’s De La Soul Is Dead, and 1993’s Buhloone Mindstate. I am not most people, though, and Stakes Is High holds a singular place in my heart, one of those musical works that sounds perfect to me every time I hear it even if it doesn’t always to others—especially if it doesn’t to others.

Stakes Is High is a product of its time, in several senses. The three years that followed Buhloone Mindstate had witnessed a sea-change in East Coast rap with the emergence of, among many others, Wu-Tang Clan, Nas, The Notorious B.I.G., the Fugees, and Jay-Z. By the time Stakes Is High came out De La Soul were elder statesmen, standard-bearers of a previous micro-generation. Stakes Is High was also the first album the group recorded without the input of Prince Paul, the antic producer whose pioneering use of skits and absurdist humor had defined both their landmark debut, 3 Feet High, and its masterpiece follow-up, De La Soul Is Dead. Heavy on funk, soul, and fusion samples laced through sticky, thumping drum loops, Stakes bears the unmistakable influence of NYC production visionaries Pete Rock, RZA, and DJ Premier. In 2016, the above names are as storied as Criminal Minded, but in 1996 they were the music’s bleeding edge.

Even by De La Soul’s standards, Stakes Is High a ferociously intelligent record, full of some of the sharpest lines in the group’s catalog. “Got the solar gravitation so I’m bound to pull it / I gets down like brothers are found ducking from bullets,” raps Posdnuous, the superfluous “are found” dropped in to extend the meter and squeeze in one more rhyme off “bound” and “down.” Or this terrific turn-of-phrase from Trugoy: “Emcees be needing dough while I make bread like Wonder,” a concise master class in braggadocio, quirky referentialism, and sparkling wordplay (“needing/kneading”).

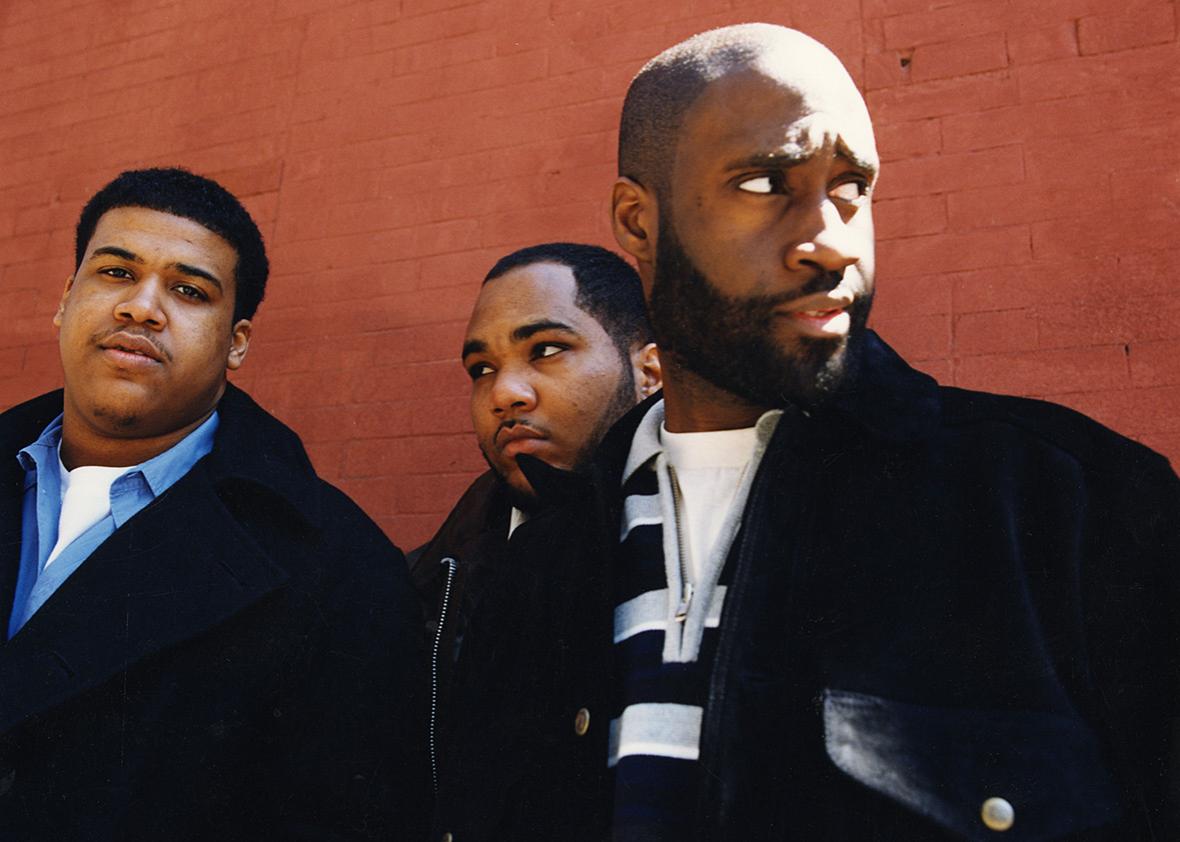

Photo by Eric Johnson. Art direction by Michelle Willems.

And yet, for all its characteristic love of music and language, Stakes Is High’s defining quality was its deep ambivalence over the state of the hip-hop itself. Stakes Is High was a darker and more confrontational record than De La Soul had previously made, grizzled, prickly, and caustic: By 1996, Pos, Trugoy, and Maseo were already relatively long in the tooth but those teeth were awfully sharp. “De La Soul is here to stay like racism,” spits Pos on the album’s opening track, stepping on that last word like a throat. But the group’s main target was a contemporary East Coast rap landscape that had increasingly given itself over to the more-stylized and spurious provocations of gangsta rap. “Itsowezee (Hot)” finds Trugoy taking shots at the ascendant genre of Mafioso rap (“Why you acting all spicy and sheisty? / The only Italians you knew was Icees”), and on “Long Island Degrees” he comes after Biggie Smalls himself (“I’ve got questions about your life if you’re so ready to die”). The album’s title track—the LP’s high point, curiously buried near its end—announced the “reinstatement” of Native Tongues, the enormously influential alt-rap collective that in the early 1990s had included De La, Jungle Brothers, and A Tribe Called Quest, and in its new version sprawled to include a raft of younger affiliates. Among them were a newcomer from Detroit named J Dilla (credited as Jay Dee), who produced the title track, and a Brooklyn MC called Mos Def, who makes one of his earliest recorded appearances on Stakes’ “Big Brother Beat.”

If the general vibe of the album sounds a little get-off-my-lawn, it is, but Stakes Is High is an album of concern rather than conservatism, walking a tightrope between the productive uses of history and the simplistic allures of nostalgia. Stakes Is High is an obsessively historical album from its opening and repeated invocations of Criminal Minded to its prominent samples of Slick Rick and Kurtis Blow on “Supa Emcees” and “Brakes,” to its shout-out to Malcolm McLaren and the World’s Famous Supreme Team’s 1982 curiosity-cum-classic “Buffalo Gals” on “Baby Baby Baby Baby Ooh Baby.” And at album’s end, they bend the flashback onto themselves as well: The final voice heard on the album intones, “Yo, when I first heard 3 Feet High and Rising I was …” and ends there, a dangling testimonial waiting to be completed. The gesture toward Criminal Minded at Stakes’ opening sounded a celebration of time past; the invocation of 3 Feet High at its close rang a note of apprehension that perhaps De La Soul’s time was passing as well. Stakes Is High is an album about the virtuous rigor of history in the face of easy narratives about past and future, a work by veteran rappers that begins as a celebration of tradition, then enfolds as a genre critique, and by its end has transformed into a genre celebration and critique of gauzy nostalgia.

Derreck Johnson

I’ve been thinking a lot recently about nostalgia, and particularly the increasing classic-rock-ification of ’90s hip-hop, as expensive reissues and lucrative reunions seem to move certain corners of the music further and further from being—as De La themselves whispered back in 1996—“the sound of the poor.” Stakes Is High is a product of its time, and aren’t we all. If you’re a hip-hop fan who went to junior high school, high school, or college in the 1990s (I made stops at all three) you grew up around an embarrassment of great music, music that’s entwined with your life in ways that can be hugely powerful. When I first heard Stakes Is High, I was 16 years old working at an overnight camp in western Massachusetts, recovering from my first real breakup, having what was, up until that point and maybe this one, the best summer of my life. These are important details to me, if less so for you, and their importance colors every word you’ve read here. I’m not sure if this is a good thing or if it’s an avoidable one.

Back in June music-critic Twitter was thrown into upheaval over a demonstratively irreverent takedown of 3 Feet High and Rising by David Turner, a young critic for MTV who’d listened to the album once and come away unimpressed. “Rap music prior to ’92—the year I was born, of course—is something I’ve struggled with a lot in my life,” wrote Turner. “Too often, going back that far can feel like a chore.” This was an honest and somewhat brave admission: Again, we’re all products of our time. The piece produced recriminations and rebuttals, some thoughtful and others less so, as well as defenses that it was an antidote to a generation of nostalgia-soaked, graying hip-hop heads and a useful piece of canon destruction. On the first point I was sympathetic: At 36 years old, I’m precisely whom the piece had in its sights, 3 Feet High isn’t actually an album I listen to very much anymore, and as music I’ll concede that it’s probably overrated.

But that “as music” is a tricky qualifier. 3 Feet High’s studied quirkiness hasn’t aged all that well (with some massive exceptions) but it opened a lane for hip-hop to move in quixotic and bohemian directions, and announced that alternative conceptions of musical blackness could be both possible and profitable in the genre. (3 Feet High hit No. 1 on the Billboard R&B album chart in 1989 and was eventually certified Platinum.) And much of the music made in its wake ranks among the most beautiful and world-expanding I’ve ever heard, including much of De La Soul’s own. When I first heard Stakes Is High I was 16 and it made me go out and listen to Criminal Minded, a towering work of late–20th century American art. Stakes Is High isn’t quite that, but it helped teach me that opening my ears to the past didn’t necessitate closing to them to the present, or future. Twenty years later, it still sounds perfect.

Slate thanks former Tommy Boy Records art director and designer Michelle Willems for her help securing the original album artwork to accompany this article and Timmhotep Aku for making the introduction.