Excerpted from The Blue Touch Paper: A Memoir by David Hare. Out now from W. W. Norton & Company.

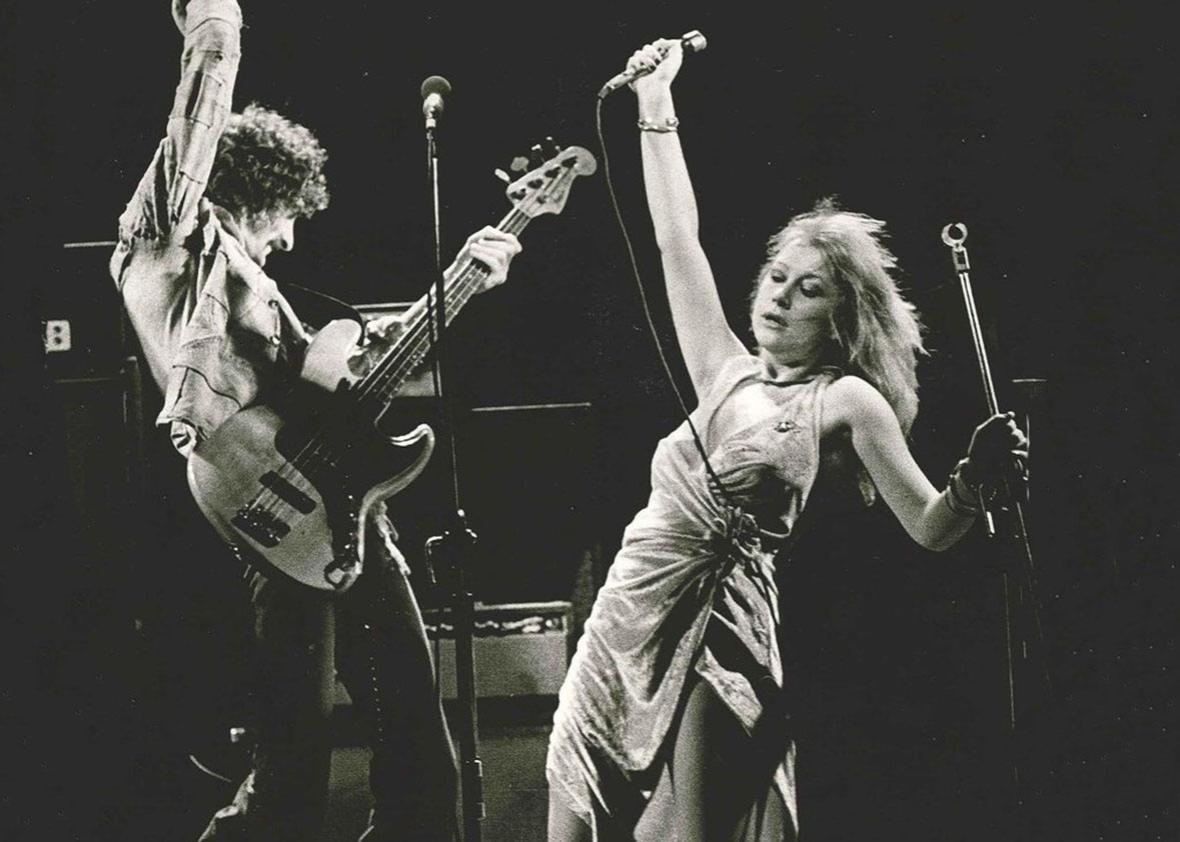

In New York, I was carrying with me some early pages of my new play. A rock band would be playing a couple of sets on the lawns at a Cambridge May Ball, and you would see both the performances they would give that night and, in between, the wild, shocking disarray they happened to be in offstage. It was a blindingly simple notion. It would not be a musical, but nor on the other hand would it quite be a play. Kicking my heels, I wandered down to SoHo, which was still in the early days of having its industrial premises taken over by painters, filmmakers, and fashion designers. Something in the atmosphere hit me strongly. I hadn’t been in the area since 1965, and clearly everybody thought he or she was very bohemian, colonizing a part of the city that had been written off as unlivable in. But if you listened to what they were talking about, people had moved from hippie to yuppie without passing through action.

I went to the Broome Street Bar to have a beer. In such bars, the talk had once been of civil rights, of Vietnam, and of revolution. These days, to judge from what I was overhearing, it seemed to be exclusively about yourself. Here, as everywhere, were hung Andy Warhol’s images of boring personalities from the past. America was looking backward, turning into a place of myth and memory. I sat there for most of an evening listening to people talking ever more loudly about their relationships. A woman on a payphone was screaming at the top of her voice, “Don’t write me. Don’t phone me. I never want to see you again.” At no point did anyone in the bar seem to discuss anything that was happening in the nonrelationship world. It struck me that the rolling stone really had rolled on down the hill and come to a complete stop. Whatever promise of insight had once been held out in the injunction to have a good time had long been snuffed out. The project was no longer to make the finest possible society. It was to gild the finest possible cage. I had given up on bands such as the Beatles years previously when they had started wittering “Let It Be.” But now it was like the weather had changed for good. Publications such as the Village Voice and Oz had looked outward. It was only a matter of time till there was a magazine called Self.

In the conception of any play or film, there is always a moment of blinding excitement, and this was it. The visual image had long been in my head—the contrast between the grungy band and the privileged surroundings. But how would it be, I thought that evening, to conceive of a heroine who refused to go down the path my own generation seemed to be taking? What if I created a rock singer who would do anything, literally anything, rather than see her horizons shrink to those of the Broome Street Bar?

On my return to London, I persuaded Tony Bicât to write the lyrics for the new play and his younger brother, Nick, to write the music. He relished the chance to come up with a proper rock ’n’ roll score. Both Nick and Tony thought that my portrait of a humorous, exhausted, and drug-taking band on the road was influenced by our own time with Portable Theatre Company. The jokes brought back memories. And fairly soon the three of us were flying, far too preoccupied with our night of stage debauchery and mayhem to take much notice when in February the Conservative Party elected a female leader. It didn’t seem an event of much significance. By the middle of April, Teeth ’n’ Smiles was finished, and I couldn’t wait to put on. I set to work with the Royal Court’s vibrant new casting director, Patsy Pollock. Our outstanding challenge was to find someone who could play Maggie.

My lasting hatred of the word self-destructive stems from the fact that I have no idea what it means. Or rather, it’s in such common and lazy use as to have no meaning at all, except presumably to convince you that the user somehow knows what he or she is talking about. When a politician takes no care to hide the fact he is sleeping with his research assistant, the word for what he does is stupid. When a rock singer dies in a pool of his own vomit, the word for him is almost certain to be addict. In my play, the central character, Maggie, is fond of a drink, and is also in a state of violent revulsion at what she sees her world becoming. As she keeps intoning satirically, “The acid dream is over; let’s have a good time.” But there is a purpose to her antics. Under the ragged surface of chaotic abuse, her ex-boyfriend, the lyricist Arthur, can detect a certain iron control. For the role of Maggie, Patsy and I therefore needed an actress who was too intelligent to buy into the newspaper myth of self-destruction. She had to be able to scare the living daylights out of every man she met but also to amaze them with her acumen. There was only one candidate. But the problem we had was that Helen Mirren couldn’t sing.

Like many first-rate teachers of music, Nick Bicât holds to the idealistic principle that there is no such thing as a nonsinger. We can all sing; we’ve just been taught wrong. In four switchback weeks of rehearsal, Nick certainly made his point. Helen was such a good actress that, standing in front of a flat-out rock band and fixing you firmly in the eye, she could make you believe she could sing by the mesmerizing power of her presence, even though the actual notes she was hitting were occasionally John o’Groats to the tune’s Land’s End.

At the time she came to us, Helen had been traveling ’round Africa with Peter Brook and was very much a believer in onstage spontaneity. She had an insouciant approach that included telling stories about the unhappy effects of imagining she could enliven her appearance in a Royal Shakespeare Company performance of The Wars of the Roses in Stratford with a few spliffs. Helen’s ways of not listening to direction were far more sophisticated than those of anyone I had previously encountered. Once she received me naked for a notes session in her dressing room. She discarded the Evening Standard, which had briefly obscured her, clearly with the aim of putting me off my stride. She succeeded. Helen’s fondness for hanging loose was fine by me—it was so unselfconscious and natural, and onstage it fed into the character—and it was also fine with Jack Shepherd, who was playing Arthur. He was an old hand who had dealt with far trickier people than Helen. He loved going out and jazzing according to whatever Helen threw at him that night. She was so accomplished that, whatever she did, she never let go of the play’s intent.

Excerpted from The Blue Touch Paper: A Memoir by David Hare. Copyright © 2015 by David Hare. First American Edition 2015. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.