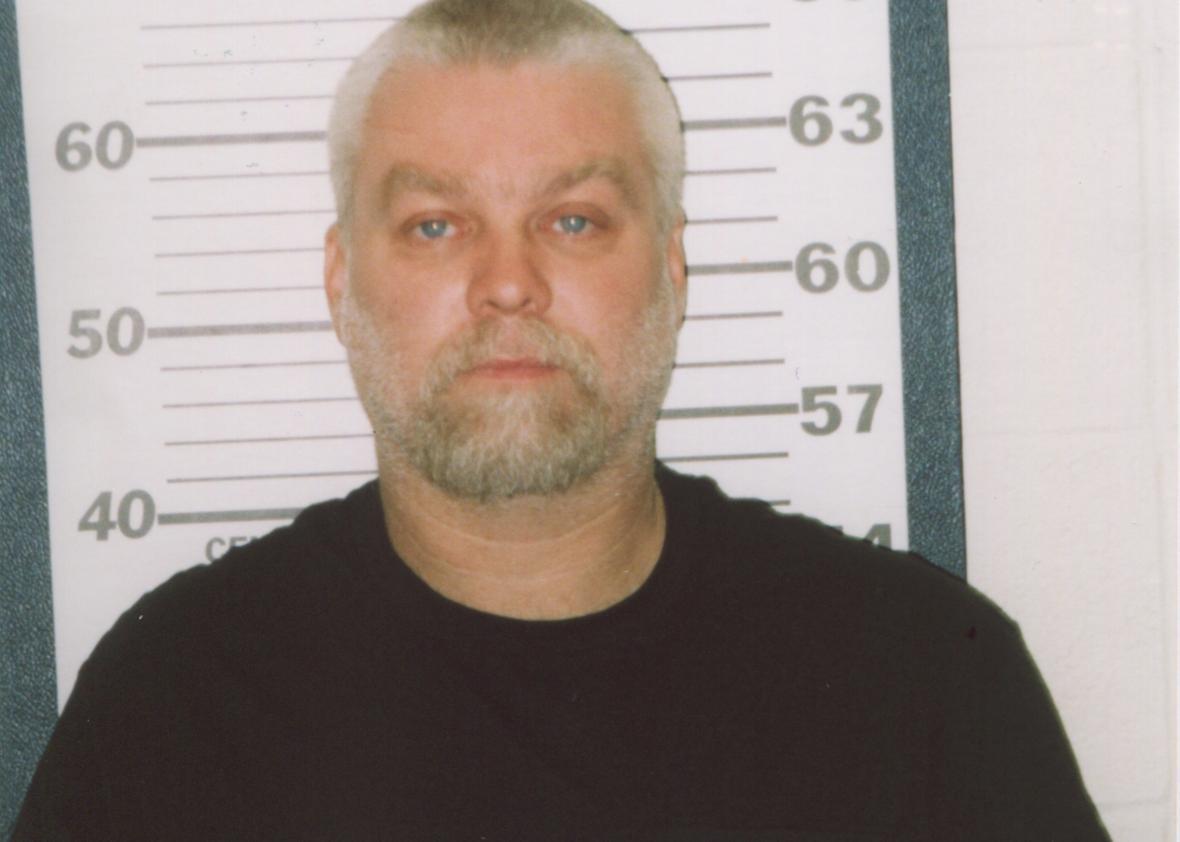

When I finished Netflix’s 10-part crime docudrama Making a Murderer two weeks ago, I gripped my head—actually gripped it, the way people do on television. Not only had the state of Wisconsin bestowed upon the American people Ed Gein, Jeffrey Dahmer, Gov. Scott Walker, and Dungeons & Dragons (not to mention the incomprehensible 2014 “Slender Man” stabbing), but now it had added to those considerable gifts a tentacled law enforcement bureaucracy concerned more with covering its own ass than with the pursuit of justice. How was it possible for one man—in this case, the poor, diminutive, cognitively underprivileged Steven Avery—to be wrongfully convicted of rape, exonerated by DNA evidence after serving 18 years in prison, then framed by the same sheriff’s department that set him up the first time, and ultimately convicted of murder? The level of moral turpitude necessary to pull that off would seem to require all the world’s crooks come together and work overtime.

From the brooding cello and martial drums of the soundtrack (highly reminiscent of the intro for another show about wrongful conviction, the Sundance Channel’s Rectify) to the long pans of the weed-choked Avery Auto Salvage yard, everything in Making a Murderer spins around an axis of desolation and decay—moral, professional, and physical. If an innocent man can be railroaded by law enforcement twice in one lifetime, I thought, then Manitowoc County, Wisconsin, must be where virtue goes to die. Even the sky that hangs over the place looks like a steel door waiting to slam shut.

And that, of course, is exactly how the directors of Making a Murderer, Moira Demos and Laura Ricciardi, want me to feel. They have constructed every frame to extract from me a sense of moral outrage that is predicated—whether the directors admit it or not—on Avery’s innocence in the murder of 25-year-old Teresa Halbach. Which is why, days later, I am as frustrated with the series as I am compelled by it. The “good” characters seem a little too good, and the villains seem a little too arch. Something about the series just feels too clear-cut, too easy, in a way I suspect the actual trial of Avery and his teenage nephew, Brendan Dassey (by far the show’s most tragic figure), were not. That suspicion has only grown, now that a number of people mentioned in the film, including Avery’s ex-girlfriend, Jodi Stachowski, are giving interviews and many of the original court documents and transcripts from the case are circulating online.

Several critics have praised Demos and Ricciardi for their neutral, hands-off decision to present the Avery saga without a narrator, and there’s no question that the format makes for a more addictive series. In this way, Making a Murderer has more in common with the Oscar-winning Murder on a Sunday Morning and Soupçons/The Staircase, two crime documentaries by French director Jean-Xavier de Lestrade, than with the other crime dramas that invite most comparisons, such as the hit podcast Serial or HBO’s The Jinx. Slate’s own June Thomas noted that “the lack of voiceover [in Making a Murderer] makes the show’s indictment of the legal and law enforcement system around Avery even more effective; it lets Ricciardi and Demos communicate their message more subtly—without the willful instructiveness of … narration—while still allowing viewers to feel as though we are weighing the evidence and deciding guilty or not guilty for ourselves.”

I strongly disagree. Viewers only feel as though they are deciding for themselves. In truth, the conclusions were set up for them long ago. Editing almost 700 hours of material into a taut 10-hour narrative for prime time (roughly 1.4 percent of the footage) necessitates abundant manipulation, but with no narrator at the helm, you are simply less aware of being manipulated. That is its own form of myopia—the tunnel vision of television, as it were—and it brings with it its own set of perils. We are being encouraged to make sweeping decisions based on minimal information—precisely the sort of rush to judgment that Making a Murderer indicts. One risk of such a gambit is that the viewer may feel lied to, or at least mildly cheated, should any glaring omissions surface later. Which I do, now that they they have.

One of the cardinal rules of the courtroom (and the newsroom) is: Don’t flinch. If there are weaknesses in your case, you should be the one to bring them up. What is dragged into the light can be explained and shelved, never to be brought up again. What is hidden, sidestepped, or glossed over will ultimately destroy your credibility, or at least call it into question. That’s a lesson I wish Demos and Ricciardi had taken more seriously.

Jurors in Avery’s and Dassey’s trials learned that, per the original criminal complaint, “handcuffs and leg irons” were found in Avery’s trailer (Avery said they were for use with his girlfriend, “like a toy”), and that DNA from Avery’s epithelial cells—not blood, but sweat, skin, or saliva—was found on the hood latch of Halbach’s RAV-4, the battery of which had been disconnected. A bullet found in Avery’s garage with Halbach’s DNA on it was fired from the same model of .22 rifle that hung over Avery’s bed, and Barb Janda, Dassey’s mother, reported that her son told her that large bleach stains on his jeans came from helping Avery clean his garage floor. What’s more, Halbach’s camera and cellphone were found with her remains in the burn pit behind Avery’s trailer, along with rivets from the jeans she was wearing when she went missing.

The issue of the cellphone is especially problematic. The series implies that whoever accessed Teresa Halbach’s phone on the day she died (which both Halbach’s brother and her ex-boyfriend admit to doing) might have been involved in her murder. But anyone with physical access to Halbach’s phone would have also been able to access her voice mail. Is that why this piece of evidence was left out?

Avery’s attorneys, Dean Strang and Jerome Buting, built a heroically convincing case that the Manitowoc County Sheriff’s Department planted some, if not all, of the evidence that seemed to indict Avery. It’s entirely possible that these other items were planted (or at least contaminated), too. If that is true, then Avery is owed a new trial, several times over. Surely Buting and Strang can explain this other evidence, since the prosecution’s theory of what happened and where is highly implausible. So why not put these answers out there for the audience to evaluate?

There are more conspicuous omissions. Multiple people living on the Avery property, including Steven’s brothers, Chuck and Earl, had criminal records involving physical violence. Avery’s own defense team outlined their backgrounds in one of its motions. The only reason not to bring this up (since these are at least two viable alternative suspects) would be to stay in the good graces of the Avery family.

What’s more, at the time of Halbach’s disappearance, Steven Avery was being investigated for the alleged 2004 sexual assault of a teenage female relative, who claimed that Avery threatened to “kill her family” if she told anyone about it. Worse, Dassey alleged in a phone call to his mother that in the past Avery had touched him in places that made him “uncomfortable.” Stachowski claims that Avery beat her repeatedly, and Penny Beerntsen, who mistakenly identified Avery as her attacker in the 1985 rape, says that Avery called her up shortly after his exoneration, asking for money to “buy a house.”

Whether or not the above pieces of information are legitimate is anyone’s guess—Avery was never tried, let alone convicted, of the alleged 2004 assault, and Dassey was so confused that he may well have said anything that anyone asked him to—but it is clear that this story goes much deeper than we have been led to believe. In the spirit of transparency, I would have liked to have known these troubling details, because I would like to feel certain that the sense of disgust that swelled over me at the end of Making a Murderer, as well as my belief in Avery’s innocence, came from having analyzed all the data. Given these new revelations, I can’t be sure that’s true.

This isn’t a referendum on artistic truth or a screed against “bias” in nonfiction storytelling. Of course there is no such thing as a view from nowhere, and the best documentarians, like the best journalists, follow their instincts and speak from their consciences. To quote the great Walter Lippmann, “There is but one kind of unity possible in a world as diverse as ours. It is unity of method, rather than aim; the unity of disciplined experiment.” In other words: Come down on whatever side you want, but make sure that your audience knows that you did your homework.

So, it’s not bias that unsettles me. Rather, it’s bias posing as impartiality that makes me uneasy. Because so much seems to have been left out, I now have lingering doubts that the directors of Making a Murderer ever gave the other side a genuinely fair hearing.

Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, the directors of the superb Paradise Lost trilogy, were consistently upfront about the injustices they felt were committed against the West Memphis Three, yet they were still able to secure interviews with the investigators who wanted to keep the three behind bars. It was largely because of the global attention the trilogy received that those injustices were (at least partially) corrected when Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin, and Jessie Misskelley Jr. were released from prison in 2011. Sometimes, artistic advocacy is a very good thing, but only when it feels complete.

Whether or not you loved or hated the evidentiary back-and-forth of Serial, Sarah Koenig excelled as an investigative reporter when it came to putting all her cards on the table. The detectives and prosecutors involved in Adnan Syed’s conviction declined to speak with her, but Koenig still managed to give the prosecution’s theory of the crime real consideration, as the jury in his trial would had to have done. That added depth and dimension to her story.

So is it fair for Making a Murderer to characterize both the people of Manitowoc County and the jury that convicted Avery as members of a mindless lynch mob if they were looking at a different, murkier set of facts?

Had Demos and Ricciardi offered a more layered portrait of Steven Avery, it would not have rendered the suffering of Halbach’s and Avery’s families, especially that of Avery’s mother, Delores, any less powerful. Those empty fish tanks that Allan Avery stares into as he contemplates all the things that might have been would be no less heartbreaking. The sheriff’s department’s obvious conflict of interest and the unctuous, Ned Flanders–esque sanctimony of Ken Kratz, the former Calumet County district attorney who was later forced to resign after a sexting scandal, would have been no less maddening. But a fuller picture would have demanded that the audience consider two other horrifying scenarios: that serving 18 years in prison for a crime he did not commit had turned Steven Avery into a predator, and/or that police may have framed a guilty man. In both, the state remains morally complicit in shoring up a corrupt legal system that is stacked against those who don’t have the resources to fight it.

There’s an interesting moment in Making a Murderer’s final episode, when Dean Strang says, “If I’m gonna be perfectly candid, there’s a big part of me that really hopes Steven Avery is guilty of this crime. Because the thought of him being innocent of this crime, and sitting in prison again for something he didn’t do, and now for the rest of his life, without a prayer of parole? I can’t take that.” But as a viewer, I felt the exact opposite: I wanted Avery to be innocent so badly that the bits and pieces of information that trickled out after the series aired were hard to swallow.

Because if Avery were exonerated of one terrible crime and went on to commit another—if a broken system broke him, too—then we may be robbed of our pity for the Averys and instead be forced to really look at them. Like the Whites of West Virginia and so many other families across the United States, they live on the margins of society with no financial, psychological, or emotional tools to navigate the world. They will get caught in its snares again, and again, and again, because they are poor and uneducated, and something about them makes people uncomfortable. They will grow up being called “trash,” they will drink and fight, but mostly they will learn to keep secrets because no one listens to them. They live in your town, and in mine.