We were about three minutes from showtime when I told the producers exactly what they didn’t want to hear. “If I make it past $100,000 and I don’t know the answer,” I said suddenly, “I’m going to walk.” The producer with whom I had been speaking looked shocked, and with good reason. Playing it safe was not the reason I had been invited back on Who Wants to Be a Millionaire. The producers wanted to see me try to beat the game. But as the cameras began to roll on the show’s first-ever Second Chance Week, I was absolutely terrified that the game might once again defeat me.

Nine months earlier, a rash decision during my first stint on Millionaire had cost me $225,000 and made me one of the biggest losers in game show history. Losing a small fortune in a split second had hurt—a lot. But I soon realized I needed to find a way to own my failure. So I resolved to let my decision to gamble my winnings on a semieducated guess—and all that choice implied about my personal tolerance for risk—change my life as much as the money would have. In the months since my first appearance on the show, I had tried to put this new philosophy into practice. I was at the stage of my life where I could take risks, after all: I had no debt, no children, no debilitating illnesses. So why not?

Now that I was back on the small, frigid set of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire, the rationale seemed clear: because failure is painful, and money is a nice thing to have. All of the past year’s regrets and self-recriminations came rushing back: the sleepless nights, the anguished days. I had returned to the spot of my failure—and my roiling emotions made me realize I had never really left it behind.

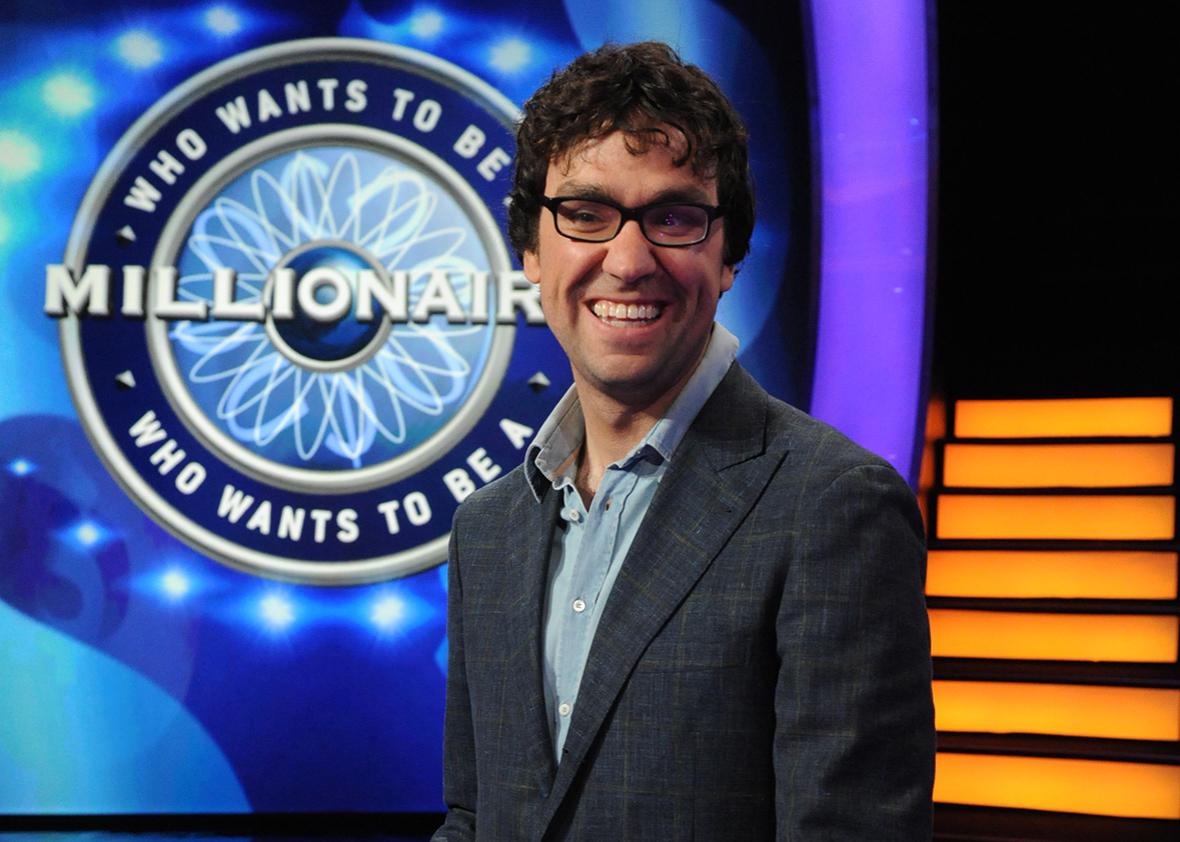

But I was running out of time to wallow in self-doubt. The show’s new host, Chris Harrison, walked onto the set, and the cameras began to roll. The stage manager cued me into position, and Harrison introduced me to the crowd. “He didn’t come back for the money—he wants redemption,” says Harrison.

Redemption doesn’t pay the rent.

“He’s here to beat the game today,” Harrison continues.

What if I go out on the first question?

“I can’t wait for this.”

I should never have come back here.

“From Lake Bluff, Illinois: Justin Peters!”

So a librarian, a prison guard, a French-Vietnamese expatriate, a trade-magazine editor, and two traveling improv comedians walk into a bar. The prison guard, who is burly and intimidating, turns to the traveling improvisers, who are anything but. “I’m thinking of moving to Chicago to get into comedy,” he says to me. “Do you think I have a shot?”

It’s the end of May, and my comedy partner and I are in Cedar Rapids, Iowa—the first stop on a Midwestern tour in which our improv duo, From Justin to Kelly, will play 10 shows across 12 dates in five different states. We booked this tour on our own, and we took a pretty substantial risk in doing so: We’ve never performed in most of these cities, and we have no idea whether anyone will actually come to our shows. After my first stint on Millionaire, I had decided to use some of my winnings to fund a comedy tour of the West Coast, unsure whether I would see any return on the investment. We didn’t make any money on that first tour, but the experience was valuable all the same. So we promptly booked another tour. And we could already tell it would be better than the first.

Courtesy of From Justin to Kelly

For about a decade prior to my first Millionaire appearance, I performed improv and sketch comedy in New York City, always wanting to make a career out of it, but never actually taking any serious steps toward making that dream come true. My inaction was a function of fear—a fear that if I tried I might not actually succeed. So there I sat, for years, in comfortable stasis, doing complacent work for indifferent audiences, hoping that the hand of God, or at least Lorne Michaels, would someday lift me out of the city’s suffocatingly sad indentured-comedy scene.

Losing $225,000 on Millionaire in October 2014—my episodes aired in February—changed all that and made me realize that sitting and waiting for great things to happen to you is a surefire way to ensure that they never will. This Midwestern tour is a function of my loss on Millionaire and my subsequent decision to embrace the idea of taking the shot, of trying things without knowing whether they’ll succeed. The risk has paid off thus far. We just performed and taught a workshop to an enthusiastic crowd at the gorgeous Theatre Cedar Rapids, and now we’re out for drinks with a bunch of friendly locals who are taking the shot in their own ways.

The prison guard is named Adam, and he is one of the most interesting people I have ever met. His menacing countenance conceals a caustic, deadpan sense of humor, which he says he has honed at his day job. “My inmates will say, ‘Hey, C.O., go bust on that guy,’ and I will,” he says, describing the many ways in which he uses insult comedy as an order-maintenance tool. “We get a lot of Latin Kings on the tier. I’ll call ’em the Lion Kings.” This joke may not look very funny on the page, but if you heard him say it, you’d be in hysterics.

Adam says his inmates have encouraged him to pursue his comedic ambitions, perhaps so that he’ll stop insulting them all the time. So he came to our improv workshop this evening; now, over beers, he expresses his hope that tonight is just the beginning of a journey that will take him to Chicago and its robust stand-up comedy scene. Adam isn’t sure he’ll succeed as a comedian—though I, for one, would certainly watch his stand-up special—but he feels compelled to try. “If not now, then when?” he asks. I know the feeling.

Of course, just because you decide to own your failures doesn’t mean that you stop regretting them. Throughout my tour, I was still dogged by the fact that I had had a lot of money and lost it. But as the months went by, the loss hurt less and less, and I found ways to benefit from weaving “massive game-show loser” into my personal story. Our improv shows had been better than ever before—there’s something about performing in a different city every night that keeps you sharp—and the crowds’ reactions were outstanding.

To be clear, not very many people came to see us. As far as most Americans are concerned, improv comedy is lower than karaoke. Though I had been on television, I was by no means famous—and as I performed more and more shows across the country, I came to think that fame, perhaps, wasn’t the point. I spent years of my life subconsciously believing that accomplishments only counted if a lot of people noticed them, and that success was measured by the number of strangers who knew your name.

Performing improv shows for 30 people in Cedar Rapids wasn’t a stepping stone to Hollywood fame and fortune. But it was intrinsically worthwhile all the same. I had wanted to take my comedic ambitions more seriously, and that’s exactly what I was doing—and the fact that I was doing it in near obscurity didn’t negate the fact that I was doing it. Going out on the road had, more than ever, convinced me that ”success” might just be a matter of doing the thing you enjoy doing and refraining from talking yourself out of doing it—of taking calculated leaps even if you’re not quite sure where you’ll land. This wasn’t a novel sentiment, but it still seemed like a valuable lesson.

But fate apparently wasn’t satisfied that I had learned it. The day after Cedar Rapids, we drove to Kansas City, Missouri, for a workshop and a show in an unused room above a dive bar in the city’s Uptown Arts District and performed for approximately 12 enthusiastic local improvisers who were on the verge of founding their own theater company. The next morning, standing on the balcony of a Best Western on the outskirts of town, I noticed I had a voice mail: “Justin! It’s Taylor from Who Wants to Be a Millionaire!”

Photo by iStock. Photo illustration by Holly Allen.

The current season of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire is its 14th in syndication, and at the end of last season, it wasn’t at all clear it would be renewed.* Ratings were low, and the show was relegated to subprime time slots in many markets. The name carries, though, so this April, Disney–ABC Domestic Television announced that Millionaire would indeed return for 2015–16—but that there would be some changes. The most significant was that the show would abandon the “shuffle” format it had used in recent seasons, in which the difficulty level and dollar value of the questions were randomized, and revert to its original format, in which contestants answer a series of questions that ascend in dollar value and difficulty. There would also be a new host: Chris Harrison, who also hosts The Bachelor and the Miss America pageant. What’s more, presumably in order to bolster ratings, the show would feature a series of themed weeks. On one of those weeks, the show was going to bring back memorable contestants from Season 13 who had answered questions incorrectly. They called it Second Chance Week.* And they wanted me for it.

At first I was ecstatic. Go back on Millionaire and possibly win more money? Sign me up! But soon my mood grew more complicated. I had moved past my Millionaire experience, or at least I thought I had. I had learned something valuable about myself; I had made “game show loser” into a badge of honor. But now they wanted to bring me back for a second chance, and the obvious implication was that I had bungled my first one.

This focus on redemption messed with my mind. The feelings all came rushing back: how much it had hurt to lose the first time, how bad I had made the people in my life feel as I struggled to process the loss, how much I didn’t want to feel those feelings again. I started to think more and more about the money—all that I had lost, and all that I could win this next time around if I didn’t screw things up. In preshow conversations with the producers, I emphasized just how much the decision to take the shot had changed my life and how I planned to be just as aggressive the second time around. But I was only telling them what they wanted to hear. Alone, at home, I recognized how I really felt. I had already proven myself willing to take a risk. If I got anywhere near six figures the second time around, I would probably take the cash.

The Millionaire news, along with some other things going on in my life, brought my work with From Justin to Kelly to a halt for the summer. Instead of touring, I started studying. I spent weeks examining transcripts of old Millionaire episodes, breaking the questions down into categories and focusing on those categories—geography, astronomy, consumer trivia—that seemed to recur most often. I had developed a hunch that the show’s writers got many of their out-of-left-field trivia questions from Reddit’s “Today I Learned” subreddit, so I combed the board’s archives, focusing on posts from April and May, when the show was renewed and the writers presumably started composing new questions. My friend Dan had agreed to serve as my in-studio lifeline, and I pressed him into service, too. “I need you to bone up on animals,” I told him the day before the taping; I checked in on him hours later to find that he had spent the afternoon studying exactly one animal: the hermit crab. “Hermit crabs are fascinating,” he said. “This is important!” I screamed.

That night, we drove to Stamford, Connecticut, where the show is taped. “Are you so excited?” my sister kept asking. “Justin, seriously. Are you so excited?” I assured her I was. But I was a wreck. It wasn’t excitement I was feeling. It was apprehension, tinged with dread. I had taken the shot and missed it once already. And I honestly didn’t know if I was brave enough to do it again.

Dan and I got to the Stamford studio early on the morning of July 24. Eight former contestants had returned for Second Chance Week—only five of them got to play in the end—and all of them, like me, had taken a risk that hadn’t paid off. I had risked and lost more than the others, but their losses were devastating, too. Though we all exchanged greetings, we didn’t talk very much; I think we were all a bit nervous about the prospect of playing the game again and anxious to prove ourselves worthy of the second chance we had been granted.

Yet as the morning went on, I imagined that the entire Second Chance Week had, in part, been contrived as an excuse to bring me back on the show. More than once production staffers told me that, while auditioning new contestants all over the country this spring, they felt they “had to find the next Justin Peters.” Some staffers informed me that I was a “legend” in the show’s production offices. Back in October 2014, after blowing $225,000, I had walked off the stage and immediately begged the producers to bring me back on the show “if you ever do one of those second-chance weeks for old contestants”—pathetically, I thought at the time. Now they’d done it. And part of me felt obliged to give them the show they expected.

Halfway through the morning, one of those producers entered the green room to give us all a pep talk. She spoke of the rare chance we had all been given, of how much the producers wanted to see one of us beat the game. We had been brought back because we had all decided to actually play during our first appearances, to grasp for glory rather than settle for some smaller reward. Implicit in that notion was the idea that we would be similarly bold in this second opportunity. She suggested that those of us who had already won $25,000 the last time should see this as a moment to actually play the game and beat it. “So make the most of this opportunity,” she said. “Because there isn’t gonna be a Third Chance Week.”

All of this was going through my mind as my second chance began, and as I watched the episode when it aired last week, my initial discomfort seemed painfully evident. Naturally, Harrison started things off by asking about my $225,000 mistake. “I’ve dreamed about it. I’ve stayed up nights thinking about it,” I said. “Ultimately, this was a victory,” and at the moment I wasn’t at all sure that was true. “If you’re standing on the edge, do you take that chance again?” Harrison asked. “We’ll see,” I replied. I secretly hoped I wouldn’t have to.

I nailed the $500 question. Ditto the $1,000 one. I started to get into the game, just like before; I started to remember that I was good at trivia, that I enjoyed being on television. I started to think that being asked to come back to play the game was its own reward and that by focusing on the money I had sort of missed the point. By the time the first commercial break came around, my apprehension had all but vanished, and I started to loosen up and banter with Harrison. “It’s gonna be interesting to see how things go with you as you keep going,” he said, after I correctly answered the $7,000 question. “I’m just gonna get even more manic and unlikable,” I replied. “Is that possible?” he quipped. It was hilarious. I was having a great time.

“I’ve noticed the more you get into this, the more nervous you’ve gotten,” Harrison said after I unleashed a primal scream upon correctly answering the $20,000 question, but if anything the opposite was true. I was becoming more comfortable with every question I answered. This, perhaps, was the point of the second chance: to prove to myself that the first time wasn’t a fluke, that I really was good and natural and funny on television; that the audiences for my comedic work will come in time, as long as I don’t succumb to cynicism or self-doubt. The dread that I felt before the game began was a product of fear—fear of failure, fear of not living up to expectations. These are all uncontrollable inputs, and I couldn’t worry about them. All I could do was live in the moment I found myself in and try to do the best with what I had to work with: my innate intelligence, my extroversion, and my willingness to make a fool of myself in front of strangers. And as I loosened up, I started to think that I could actually win.

Much of my early success in my first Millionaire appearance was due to the easy stack of questions I had been given. If anything, the questions were easier the second time around. The producers like it when contestants talk out their answers, which I was happy to do, but honestly I knew almost every single answer as soon as I saw the question. The money kept accumulating. At $30,000, I started to get cocky again. “I’m sure it’s not lost on you that you’ve now broken your record,” Harrison said, noting that I had banked more than I took home during my first appearance. “Thirty thousand dollars is more than $25,000, but you know what else is more?” I said. “Fifty thousand dollars, then $100,000, then $250,000, then so on and so forth.” I brought my friend Dan down to help me out with the $50,000 question, but I was pretty sure that I already knew the answer. Dan confirmed my initial hunch, and soon that $50,000 was mine. As the time expired for the first day’s show, I had two lifelines left, was four questions away from $1 million, and felt extremely confident that I would get there. As we readied ourselves for the second day’s show, a producer came around to check on me. “I was born to play this game,” I told her. I believed it.

Courtesy of David E. Steele/ABC

Then came the $100,000 question—and, in what could have been considered a stroke of luck, it was a question about the media. I spent five years covering the media for the Columbia Journalism Review, so you’d think that this would have been the perfect question for me. Unfortunately, I spent very little time covering broadcast radio, and thus I had no special insight into the question:

While each is featured on at least 500 stations, which of these does the 2015 World Almanac NOT list as one of the top four radio formats in the U.S.?

A. Country

B. Top 40

C. News/Talk

D. Sports

I didn’t know the answer, but for some reason I convinced myself that it was D, sports. I guessed, though it wasn’t actually a real risk. The show had implemented new “thresholds” for the current season, where if you made it to $50,000, you would take home at least that much money no matter what. So it was a free guess, in other words, and I took it.

I was wrong. It was B. And as Chris Harrison informed me of my error and thanked me for playing, I felt a strange sense of peace. “It was one of those questions where you either knew it or you didn’t,” Harrison told me as we shook hands before I departed. Yes and no. In retrospect, I should have remembered that my father listens to sports radio every morning in the shower and perhaps interpreted that weird habit as some indication of the format’s popularity.

Would I have chosen to guess if I had made it to, say, $250,000, and actually stood to lose money if I had answered incorrectly? I honestly don’t know. I like to think that I would have, but I’m sort of glad I didn’t have to find out. Though I was disappointed that I had answered incorrectly—and though I would spend a lot of time later picking through the flaws in my reasoning—I wasn’t devastated; $50,000 is a lot of money. “I have no regrets,” I said as my segment concluded and the next contestant got ready to play, and I meant it. I had doubled my winnings from my first stint on the show, I didn’t leave any cash on the table, and I had delivered 1⅓ episodes of good television. I didn’t beat the game, no. But I had certainly made the most of my second chance.

“Are you OK?” my sister asked as we drove home. “Yes,” I said. “Are you sure?” she asked. “Well … ” I said. “You’re not OK,” she replied. “You thought you were going to win.” And I did think I was going to win! I almost always do, and I’m not always sure whether that trait is a blessing. “I wanted to win,” I admitted. “I thought I was gonna. Like, what a great ending that would have been. What a great resolution to this story.”

“But that’s not what this was,” my friend Dan replied. “It’s not a story, Justin. It’s not a redemption or, like, a transfiguration. It’s just a game show. And sometimes you know the answers, and sometimes you don’t.” I knew the answers up to a certain point. Then I didn’t. But if my first and second chances on Who Wants to Be a Millionaire have taught me anything, they’ve taught me that it’s OK to fear the unknown, but it’s not OK to spend your life trying to avoid it. You can try to write your own story, but it will probably end up being more exciting and fulfilling if you come to terms with not necessarily being able to control the ending.

Courtesy of ABC

In a few weeks I’ll get a check for $50,000, which after taxes will probably come out to $35,000 or so. That is a lot of money. I don’t know what I’ll do with it, though I’m certainly open to suggestions. I know that I’ll keep on touring. I’m heading out on a short one this weekend. (If you live in Richmond, Virginia, or Baltimore, come out and see me!) But I’ll probably use some of this money to explore some new unknown—to run toward the next stage of my creative career, to never remain stuck running in place. This is the beginning of something, and I don’t know where exactly it’s going, and I’m not sure what the end is, but I cannot wait to find out.

Correction, Nov. 20, 2015: The article originally misstated that the current season of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire is its 16th. It is its 14th in syndication.