The shock and awe of Amazon’s new series The Man in the High Castle comes mostly from stuff and settings. It depicts an alternate 1960, in which America lost World War II and is occupied by the Nazis (the Northeast and Midwest) and Japan (the West Coast), with a strip of neutral territory surrounding the Rocky Mountains running down the middle. Struggling to animate some fairly weak characters, it leans heavily on the disorienting impact of its rich, meticulous visual design: swastikas emblazoned on everyday objects like cigarettes; familiar San Francisco street scenes with the signage all in kanji; a happy, wholesome, Cleaver-esque family sitting down to breakfast with a son in a Hitler Youth uniform. In the threadbare neutral zone of the series, you can still glimpse a bit of Americana among the shuttered and peeling storefronts—a Chevrolet sign, for example—all of it so rundown, grimy, and obviously defunct that it’s already half fossil.

This is the world Philip K. Dick created for the series’ source, what’s widely considered his best novel, published in 1962. But the new TV series is so alien to the book in spirit that it would be a shame if it came to supplant our understanding of what is also one of the best mid-20th-century American novels about colonialism and its corrosive effects on the human psyche. The Man in the High Castle is a strange, mournful story in which not very much happens to people who have very little control over their lives and even less inclination to do anything to change that. It ought not to be engrossing, yet it is. The series’ creators have tried to pump up its premise into something that can sustain a 10-episode season (or more) by giving Dick’s dystopia an element that it utterly lacks in the book: an insurgency dedicated to fighting the twin fascist regimes that control the former United States. The people in Dick’s novel never consider resistance. They’re not heroes, and that, paradoxically, is exactly what makes them so arresting.

Pop culture has exalted many of Dick’s wilder stories and novels. Since the release of Blade Runner (1982, based on the short novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?) and Total Recall (1990, based on the story “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale”), his pet motifs of false realities and artificial identities have captivated filmmakers. Some of them have made movies explicitly derived from Dick’s work, like Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report, while others have taken quintessentially Dick-ian concepts and spun them off into original works: The Truman Show, The Matrix, Memento.

Along the way to becoming popcorn entertainments, Dick’s motifs have shed a lot of their existential baggage. Today, the revelation that capsizes everything a movie character once believed about himself and his world is just another mind-blowing plot twist. No sooner have we gasped Whoa! than the film has moved on to the next chase scene, martial-arts display, or explosion. Nobody sits around questioning their own reality or humanity the way Dick’s protagonists do. Those questions, however, were the whole point of Dick’s fiction, and if The Man in the High Castle has fewer of the reality-inverting narrative pyrotechnics of his other works, it still asks them insistently.

The novel (unlike the series) takes place mostly in the Japanese-occupied Pacific States of America. It has no central character, but the closest thing to an admirable person among the handful it follows is Mr. Tagomi, an elderly official of the Japanese Imperial Trade Mission. Not coincidentally, Mr. Tagomi —the character least altered by the producers of the TV series—was also the initial inspiration for the novel. He popped into Dick’s mind after a two-year dry spell, while the author was driving to a cabin just north of his home in the San Francisco Bay Area. “I saw him seated in his office,” Dick later wrote to a friend of this unassuming gentleman, “keeping the ultimate of evil at bay in his own small fashion. And, with no further planning or notes, I wrote the book.”

But if Mr. Tagomi is the novel’s most admirable character, the most memorable opens the book: Robert Childan, proprietor of a shop dealing in “American traditional ethnic art objects,” like Mickey Mouse watches and Civil War recruitment posters. He caters to wealthy Japanese collectors captivated by the quaint, crude, vanished culture of their new(ish) territorial possession. Most of the characters in The Man in the High Castle hail from this middling social stratum: shopkeepers, skilled artisans, bureaucrats, a judo instructor. Childan—a man who has just enough to worry about losing it but no real power of his own—epitomizes them.

Childan does appear in the TV series, but rather late and in an ancillary role to the rote main story of how some attractive but dull young people become involved with the resistance. Nevertheless, the series does stage the novel’s finest scene, in which a thrilled Childan accepts a dinner invitation from a cultured Japanese couple who have visited his store. This promises more than just business success: “It was a chance to meet a young Japanese couple socially, on a basis of acceptance of him as a man rather than him as a yank or, at best, a tradesman who sold art objects … Would he do the right thing? Know the proper act and utterance at each moment? Or would he disgrace himself, like an animal, by some dismal faux pas?”

His mood fluctuating between abject gratitude, exhilaration, overconfidence, mortification, and resentment, Childan botches the evening. His disdainful remarks about “Negro music” (his host favors “authentic American folk jazz”) and Jews offend his liberal-minded clients and soon his fawning curdles into bile. He starts out marveling at his hostess’s beauty (“We are half-baked compared to them. Allowed out of the kiln before we were fully done”) and then, stung by rejection, consoles himself with assurances that “only the white races endowed with creativity … And yet I, blood member of the same, must bump head to floor for these two. Think how it would have been had we won! Would have crushed them out of existence.”

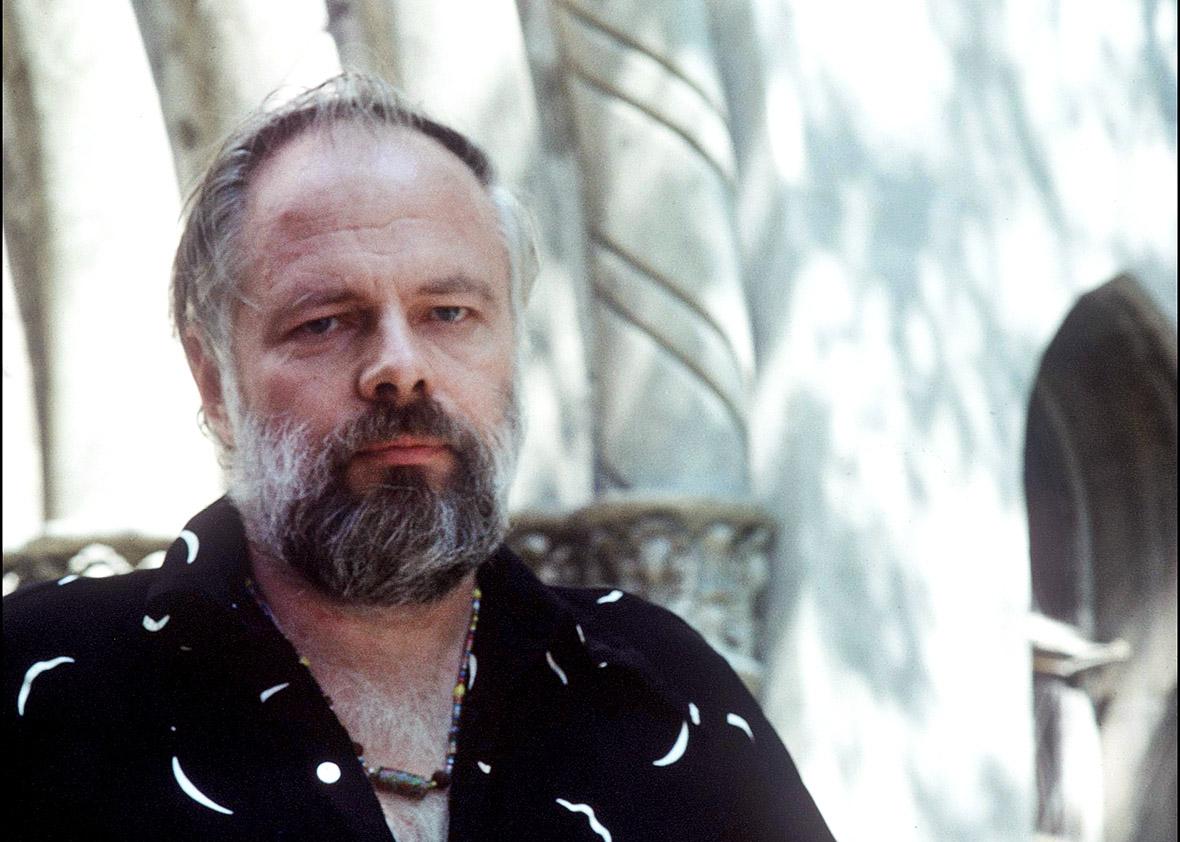

Photo by Philippe HUPP/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

The scene is both excruciating and delectable, recalling such documents of the tortured sentiments felt toward Britain by its colonial (and postcolonial) subjects as Hari Kunzru’s The Impressionist and V.S. Naipaul’s A House for Mr. Biswas. The artifacts blithely viewed in our world as the emblems of a triumphal Americanism have become, in the world of this novel, hobbies for members of a foreign ruling culture who think they understand and appreciate them better than the careless natives. “Doing my best to be authentic,” the wife explains to Childan while serving an all-American meal of steak and baked potatoes: “for instance, carefully shopping in teeny-tiny American markets down along Mission Street. Understand that’s the real McCoy.”

For all of the American characters in The Man in the High Castle, such incessant humiliations, tiny and not-so-tiny, are the stuff of everyday existence. They have largely resigned themselves to never regaining control of their country; doesn’t the fact that they’ve lost it prove that they didn’t really deserve it in the first place? The only person who has dared to imagine otherwise is the title character, the author of a book that is, like The Man in the High Castle itself, a work of alternate history—in this case, one in which the Allies defeated the Axis powers. The book does not, however, describe the world we live in, but yet a third world, in which the Soviet Union never emerges as a world power and Britain and the U.S. end up facing off in a struggle for world dominance.

The Man in the High Castle ends enigmatically, with a classic Dick reality-flip, yet the strength of this oddly powerful little book is how convincing Dick’s fake world seems. That’s because the people in it behave not like the defiant heroes of Hollywood films (or bingeworthy television programs) but the way most human beings do, letting their lives be shaped to fit a world that treats them more or less fairly depending on which straw they happen to draw. A single event—in the novel’s world, the assassination of FDR in 1933—can set history on a different course, and the triumphant occupier can easily become the abject occupied. It is less a matter of character (national or personal) than of happenstance. “Chance. Accident,” one character muses, “And our lives, our world, hanging on it.”

Most of the characters in The Man in the High Castle, white and Asian both, use the I Ching, an ancient Chinese divination method, when faced with a conundrum. So did Dick in writing the novel. He claimed that he cast an I Ching hexagram whenever one of his characters felt moved to consult “the oracle,” and then he adapted the unfolding plot of the novel to the results. Perhaps the particular charm of the novel lies in this dash of the haphazard, a shard of the cold, cold universe rather than the sliver of ice that Graham Greene claimed was lodged in every writer’s heart.