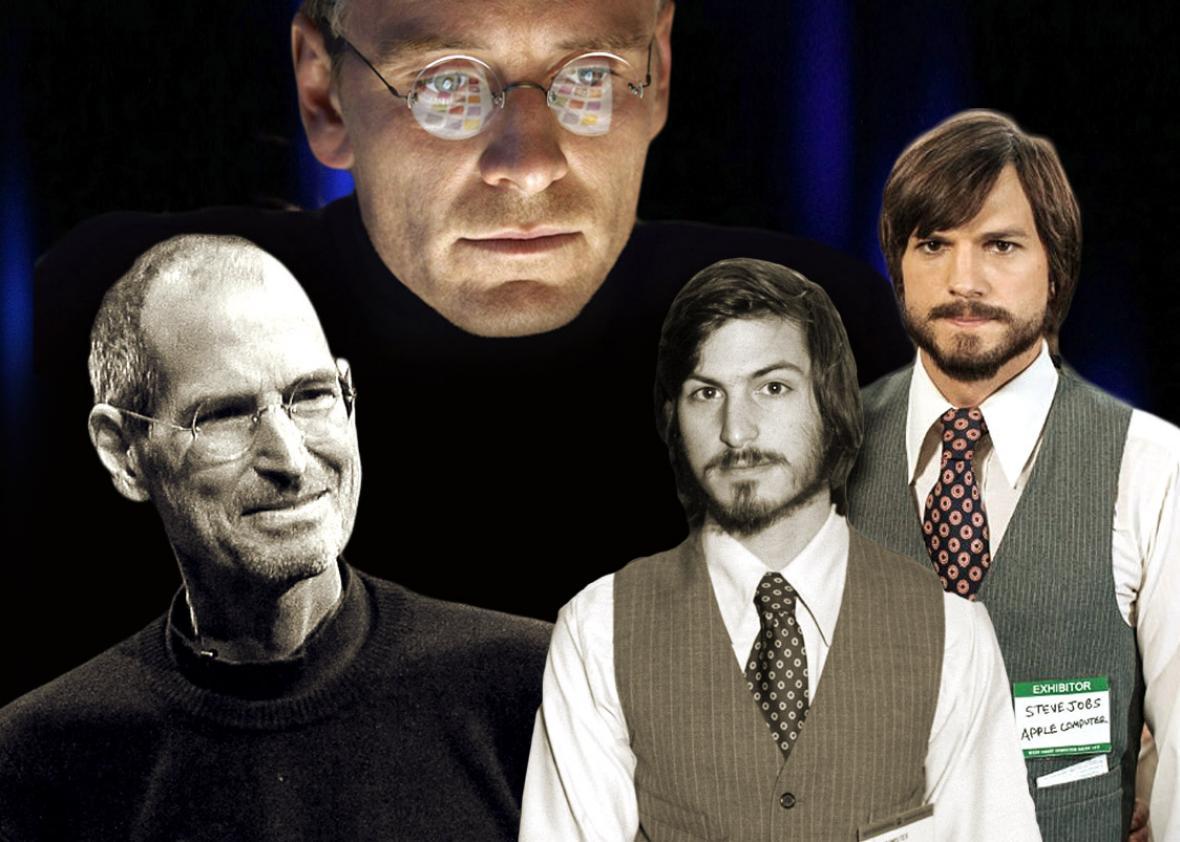

When people feel compelled to tell each other the same story over and over again, there’s usually something about it they can’t quite work out. Each iteration promises, yet fails, to finally make sense of it. The life and work of Steve Jobs is that kind of story, and our preoccupation with telling and retelling it points to some sizable cracks in the American psyche. In addition to Steve Jobs, the just-released Danny Boyle/Aaron Sorkin biopic, we’ve had Jobs, a limp 2013 film starring Ashton Kutcher, and a critical documentary released earlier this year, Jobs: The Man in the Machine by Alex Gibney. In print, the bible remains Walter Isaacson’s best-selling authorized biography Steve Jobs, published just after the Apple founder’s death in 2011, but Jobs’ friends, colleagues, and family have recently advanced an alternative, Becoming Steve Jobs: The Evolution of a Reckless Upstart Into a Visionary Leader by Brent Schlender and Rick Tetzeli.

A big chunk of the demand for Steve Jobs books can be written off to the inspirational-business market, managers, and would-be entrepreneurs who devour biographies of successful titans of industry in search of tips and motivation. But Steve Jobs represents far more than that. Jobs: The Man in the Machine opens with footage of ordinary people all over the world, weeping and laying little offerings outside Apple stores or holding up iPads displaying videos of lit candles. Gibney pronounces himself “mystified … I’d seen it with John Lennon and Martin Luther King, but Steve Jobs wasn’t a singer or a civil rights leader.” Sure, 30,000 spectators turned up for Henry Ford’s funeral in Detroit, but the grief for Jobs dwarfed that, reaching across the globe and deep into the hearts of people with no particular connection to or love for industry. Even some Occupy Wall Street protestors tweeted out their sincere respects at the death of a man who was once CEO of the world’s most valuable corporation.

Ford is probably the closest parallel to Jobs in American history, not truly an inventor or creator but a synthesizer, marketer, and seer. In the cinematic Steve Jobs, Jobs’ sometime collaborator and Apple co-founder Steve “Woz” Wozniak (played by Seth Rogen) confronts Jobs (Michael Fassbender) and asks, “What do you do? You’re not an engineer, you’re not a programmer, you can’t design anything. What do you actually do?” Jobs’ response is that he plays the orchestra, like a conductor. Woz complains that this response doesn’t actually mean anything, but the very existence of the film proves him wrong. Woz is an engineer of enormous talent, and a much beloved figure in Silicon Valley, but Aaron Sorkin is not writing a screenplay about his life. Woz isn’t the subject of street art. Jobs was a public figure of another order—the messiah of high tech, but also a symbol whose full import can never be conclusively nailed down.

One of the fiercest contests over Jobs’ meaning has to do with his infamous behavior in both his personal and professional life. He could be, as countless people who worked with him have attested, an asshole. He screamed insults at subordinates who failed to live up to his perfectionist standards, made impossible demands, took credit for other people’s ideas, and treated anyone he regarded as less than an “A player” as if they didn’t exist. Most damning of all, in the late ’70s, just as he and Woz were launching Apple, Jobs got his on-again/off-again girlfriend, Chrisann Brennan, pregnant and for several years afterward denied that their daughter, Lisa, was his child. Brennan has written her own memoir of Jobs, The Bite in the Apple, portraying him as a narcissistic monster who scrimped on child support even after he became a multimillionaire.

No one denies any of this, not even Jobs partisans. Isaacson describes the imperious CEO, when hospitalized for the cancer that would ultimately kill him, demanding that hospital staff bring five different versions of a mask so that he could pick the one whose design least pained him. Sorkin has Jobs threatening to publicly shame software designer Andy Hertzfeld, a core member of the Macintosh team, if he doesn’t get the machine to talk to the audience at an imminent presentation to Apple shareholders. (This did not actually occur.) The film, whose three acts take place backstage at three different product launches—in 1984, 1988, and 1998—puts at its center Jobs’ evolving relationship with Lisa Brennan-Jobs, from apparent indifference at the Mac launch to a tentatively self-aware reconciliation just before the debut of the iMac, the computer that resuscitated Apple and set it on the road to its current preeminence. But even “reformed,” Fassbender’s Jobs remains almost reptilian in his coldness—except when he’s ranting about the epochal nature of his products, likening one to the victory of the Allies in World War II. (You would never know from this performance how readily the real Jobs burst into tears at work.)

He’s impossible and abusive, yet he’s a great man. Even Gibney, the sharpest Jobs critic in this bunch, doesn’t doubt that he “changed the world,” a refrain that echoes through every version of Jobs’ life. The possibility that the personal computer, the portable MP3 music player, the smart phone, and the tablet might have, in time, emerged in more or less the same form rarely gets considered, even though Jobs didn’t actually invent any of these devices. Every variant of the Steve Jobs story subscribes heavily to what’s known as the Great Man theory, first promulgated by the Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle in the 19th century. It holds that history is driven and shaped not by large social or economic forces but by the will and vision of certain extraordinary individuals, men Carlyle dubbed “heroes.” In a paean that seems to predict Apple’s “Think Different” ads, he explained: “They were the leaders of men, these great ones; the modelers, patterns, and in a wide sense creators, of whatsoever the general mass of men contrived to do or to attain; all things that we see standing accomplished in the world are properly the outer material result, the practical realization and embodiment, of Thoughts that dwelt in the Great Men.”

The quintessential Victorian, Carlyle mostly believed that Great Men were fundamentally virtuous, but he did insist “herohood is not fair-spoken immaculate regularity; it is first of all … Courage and the Faculty to do.” This, presumably, is why Oliver Cromwell and Napoleon make the grade, despite their many demonstrations of ruthlessness and brutality. A hero imposes his will upon the chaos of the world, and the magnificence of the results justifies the blood and guts it takes to achieve them. Or, as Jony Ive, Apple’s head of design and a Jobs favorite, said earlier this month at a conference in San Francisco: “You could have somebody that didn’t ever argue, but you wouldn’t have the phone you have now.”

Becoming Steve Jobs finds favor with Jobs intimates like Ive and current Apple CEO Tim Cook because it presents Jobs as having matured during his period of exile from Apple, after he was forced out of the company by then-CEO John Scully in 1985 and before he was invited to return in 1996. The Steve Jobs of that initial Apple stint, the authors write, “was really nothing more than a spoiled brat.” Far from nursing an inferiority complex caused by the knowledge that he had been adopted, as Isaacson proposes, he “had always gotten his way with his parents, and had brayed like an injured donkey when things didn’t turn out as he planned.” But after suffering the failure of his pet project, the NeXT computer, and observing in action “one of the most extraordinary managers in the world”—Ed Catmull of Pixar, the fledging computer-animation company Jobs cofounded in 1986—he was chastened. The Jobs who returned to a flailing Apple in the ’90s was a man who had learned patience, a bit of circumspection, and how to “give good, talented people the room they needed to succeed.”

Whether this is true is debatable, but it betrays how uneasy we’ve become with the autocratic model of the Great Man. A good leader, by 21st-century standards, is a collaborator, skilled at enlisting employees in decision-making and ensuring that they feel appreciated. In a piece for Wired about how Isaacson’s biography has influenced bosses, Ben Austen reports that Jobs’ example has encouraged some businesspeople to reject this approach—what one management professor calls “a bovine sociology in which happy cows are supposed to produce more milk”—and think of themselves instead as visionaries whose dreams ought to be realized whatever the human cost. But others, Austen avers, have pulled back, afraid of alienating everyone around them and ruining their relationships with their families.

“What you make is not supposed to be the best of you,” Jobs’ right-hand woman Joanna Hoffman (Kate Winslet) says to him in Boyle and Sorkin’s film. But what if you’re Shakespeare, or Einstein, or even Aaron Sorkin? What then? Doesn’t a legacy like that outweigh a few hurt feelings? While the ostensible theme of Steve Jobs is that Jobs’ most important task is to repair his relationship with Lisa, the screenwriter cannot resist getting in a dig or two at those who dare to question his own genius. A running gag about (entirely fictional) objections to the skinheads hired to act as extras in Apple’s celebrated “1984” commercial is Sorkin’s dig at every critic who pesters a true creative genius like himself with their picayune ideological quibbles. At one point in Steve Jobs the camera briefly cuts away to Jacques-Louis David’s equestrian portrait of Napoleon. Sure, that’s a joke about Jobs’ grandiosity, but how else do you end up depicted as a larger-than-life conqueror by the greatest painter of your time if not by being Napoleon? No one wants to be trampled by the Corsican’s horse as he thunders on toward Austerlitz, but in the dreams kindled by the endless retelling of Steve Jobs’ story, that’s never the role we play.

Was Jobs a latter-day Napoleon, though? Only Gibney, whose documentary wades into the muddy waters of working conditions at Foxconn and an investigation into backdated stock options, wonders if he might not have been. Sure, Jobs succeeded in his promise to “put a dent in the universe,” but now he’s left us with a dented universe, and who’s going to pay for that? Gibney confesses to his own enthrallment to his iPhone, how “when it was in my pocket, for every idle moment, my hand was drawn to it like Frodo’s hand to the ring.” Jobs’ greatness is directly proportional to the peculiar fascination his products inspire, and it’s not as though we aren’t ambivalent about how overwhelming that fascination can be. Wearily, the journalist Joe Nocera, who often covered Jobs, tells Gibney’s camera, “The real magic of it is that these myths are surrounding a company that makes phones. A phone is not a mythical device. And it sort of makes you wonder less about Apple than about us.”

These aren’t the only contradictions Jobs presents us with. He was a dictatorial elitist who promised to liberate everyone’s creativity. Yet he almost certainly would have scorned as “shit” the stuff that most of us “bozos” have been empowered to make with his tools. He embodies, in a single person, the chief paradox of American culture: We want a democratic social order that recognizes and appreciates what each of its members has to offer. And we also dream of individual exceptionalism, triumph, and unfettered success. It’s an equation we can’t make add up, so back to the chalkboard we go, to give it yet another try.