The latest HBO project from David Simon is the miniseries Show Me a Hero, which details a late-1980s fight over a public housing development in Yonkers, New York. Based on a true story, it touches on many of the issues that have long fascinated Simon: race relations, corruption, and the inner working of cities. A former crime reporter at the Baltimore Sun, Simon went on to serve as a writer on the NBC show Homicide: Life on the Street (which was adapted from a book he wrote) before creating The Wire, the already canonical depiction of a place that has lately been at the center of so much commentary about the ills of modern-day America.

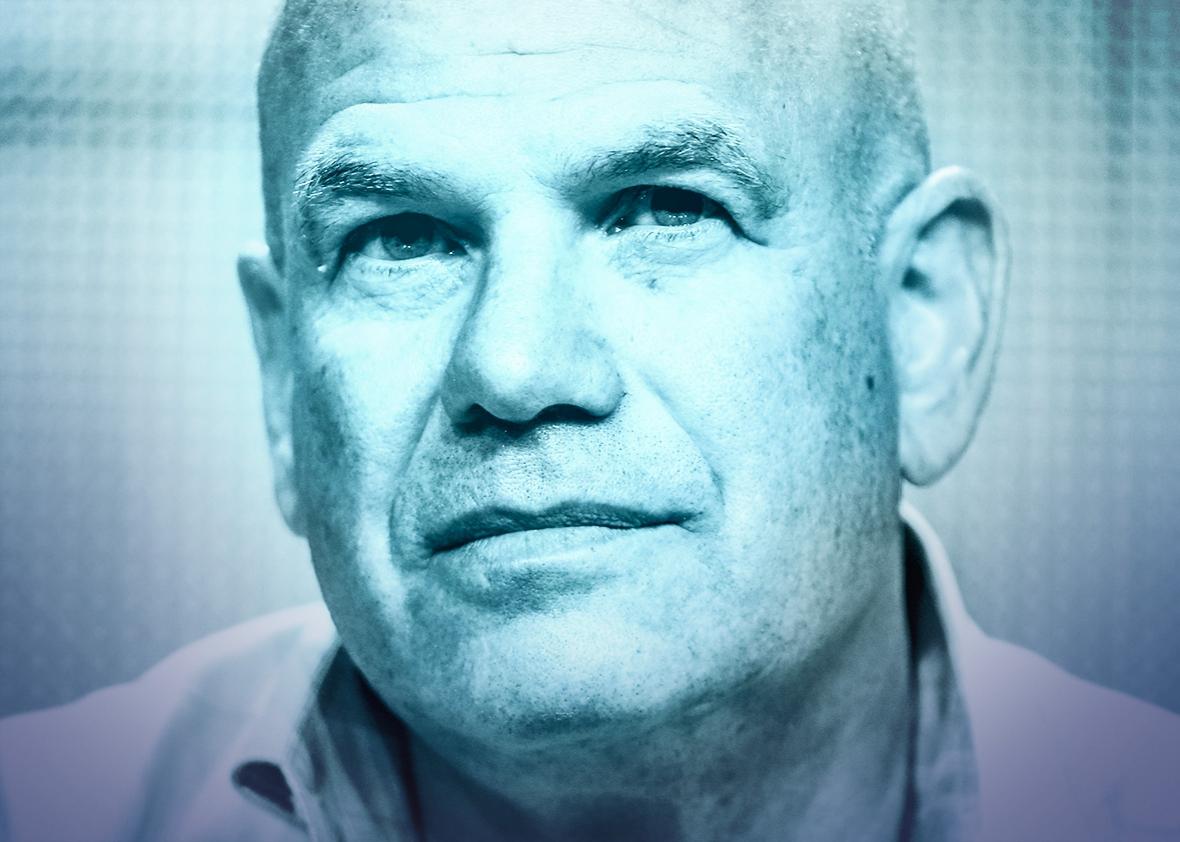

I spoke with Simon this week about his new show, the events that followed the death of Freddie Gray, and why an end to the drug war could radically change American life. The conversation has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Isaac Chotiner: The Wire had five seasons and each season showcased a different aspect of the city. I’m wondering if you think about your career in terms of shows, with each show representing an aspect of some larger vision, and if so what this new show represents.

David Simon: I don’t know if I can parse it that cleanly. I certainly don’t want to tell the same story twice. The reportorial instinct is to find some other friction point in society and attend to that, and find a narrative to discuss something fresh, something we haven’t argued about yet.

It’s interesting that you said “reportorial instinct.” Is that what drives the creation of your shows?

I think so. That doesn’t mean we aren’t behaving as dramatists, because we are. And I am not suggesting in any way that what we are producing is journalism. It is not. But the things that made me interested in being a newspaperman or a journalist remain my motivations. I understand that I need to be entertaining. But I am not particularly interested in making the most entertaining stories unless they are actually contending with an argument that matters. That’s been static throughout my entire life as a writer.

Different people go into journalism for different reasons: to tell stories, to report on things that lead to social change, etc. I don’t know if you consider yourself an activist, but do you hope that people watch your shows and come to conclusions about the kind of policies they’d like to see? Do you work with that utilitarian mindset?

I am thinking with a utilitarian mindset, but I am not actually believing that my storytelling will lead directly to fixing anything. I didn’t believe that when I was doing straight journalism, maybe as a defense mechanism. In all my experience of doing straight journalism, I found that the only way to behave and not drive yourself crazy was to not hold yourself responsible for actually fixing anything. It isn’t in your job description to fix anything. That doesn’t mean I don’t believe in the process or hope for the best. I am not a libertarian. I believe in governance. I believe in good governance as being a goal.

If it’s about hangings pelts on my wall, or winning prizes, then it’s a game. If it’s about telling a story as well as you can, then I have some place to stand on.

I heard that you said, during an event where members of The Wire’s cast read testimonies from Baltimore residents after the death of Freddie Gray, that art or drama or television shows are not appropriate venues for addressing the protests and riots. Rather, journalism is the venue.

That’s a little too broad. What I was saying was, right now, we shouldn’t be attenuating our attentions through a television drama. We don’t need that right now. At some point someone may find a meaningful drama to explain this moment. If not in Baltimore, then maybe Ferguson or Charleston or somewhere. There is a lot that drama can do, and it certainly has a role. But right now it struck me as being inappropriate, that with all the actual substance of what is happening in the streets right now, in the halls of power right now, we need to be straining this through a drama. Why are you doing that? What was it that made people at various publications and blogs reference The Wire just because it was black people in Baltimore? That’s fucked up. It’s almost a shrinking of the human mind. Why don’t you attend to what’s actually happening right now in Baltimore? You don’t need McNulty or whoever to access it.

There is a line from Marx about people seeing foreign things and translating them back into languages they understand.

Right, there were a string of essays: The Wire does explain Baltimore, The Wire doesn’t explain Baltimore. And then there were my limited comments about the protests, which I very much supported and wish were more ongoing because I don’t think there has been very much systemic change in Baltimore regardless of the indictment of those officers. My concern was the moment it went to burning and looting.

At that moment I am speaking not as the guy who did The Wire. I am speaking as someone who has covered this stuff for 20 years in Baltimore and lives in Baltimore. That was written in sight of the fires. I am completely indifferent to the notion of white privilege, that I am some rich white writer deigning to give an opinion about what poor black folks should do when one of them dies in the back of a wagon. I am sorry, but if your definition of white privilege now extends to people who have lived in Baltimore for decades and can’t say, “Please don’t burn this town down,” while in the previous breath saying, “Yes, we need answers, but please don’t burn this town down”—if that’s white privilege, then white privilege means nothing.

It seems like you are expressing annoyance with some of the political dialogue about these issues that—

What I am saying is, everything is not The Wire.

Well, wait, are you saying that, or are you saying that there is a way in which this stuff tends to get discussed among people sympathetic to the protests—

No, I am not saying the second thing. The second thing, by the way, is obvious. It doesn’t need saying by me—that there are people on all sides of this issue, that there are people who will excuse any act of violence by citing the desperation of people. Yes, there are people capable of rhetoric going in that way. And there are people who see everyone in the street demanding change as a thug. I don’t truck with either of them. But that is not what I am complaining about. You asked me a question about The Wire, right? I am on point to what you asked me about.

I am so used to the people I interview drifting off point that I can’t even fathom this.

OK, the actors at the festival were presenting themselves as the cast of The Wire doing something in the wake of The Wire. I was very concerned about that. I say this as someone completely invested in the place. A quarter of our population disappeared after the ’68 riots. To be reading people in New York or London or Los Angeles or these first-tier cities, where their economies are so secure … it’s one thing to say they understand the rage, the impulse. It is another thing to say, merely because you label someone burning a liquor store an uprising, it is.

I don’t want to suggest that those Wire cast members in Baltimore didn’t turn out to do exactly what they should have done: channel the words of Baltimore residents. They used their experience to narrate. And that felt exactly right. What I was cautious about was people feeling the need to strain what happened in Baltimore through a fictional narrative.

I have heard you say that one reason this conversation about Baltimore and other places is happening now is technology: police body cameras, cellphone videos—

Absolutely, incredibly liberalizing.

Right, so I am wondering how that has affected your view of technology, and—

What do you think my view of technology is?

I don’t know. That’s why I am asking.

OK, I am certainly as impressed with the reach of the pocket camera as everybody else.

Right, I was going to try and connect this with other technological innovations: There has been a lot written by you and others about the decline of local media and newspapers and what that means for cities. But many of these protests have gained traction through social media, and a lot of the anger over police shootings has been fueled by social media.

I certainly think that social media and its initial discoveries, either through raw footage or instantaneous knowledge, can provide much more intake for our media culture. But I know from having examined social media, and its uses, not just as pure information but as that which serves an agenda, that it is not necessarily accurate. The people who are professionals at trying to figure out what the whole story is, or why what’s posted might not be exactly what people say—the people who attend to that and force some credibility into the discussion, they have been marginalized.

At the same time I wouldn’t want to go back to a time where a police officer can kick the shit out of a guy in front of five witnesses and if they all have criminal histories, and can be made to look equivocal in front of a grand jury, he gets away with it.

I also covered a lot of cops who, because they were compelled to police an inner city, under the heel of a drug war, they had to get out of a car and clear corners. And when they said a corner was indicted, everybody move along, and one guy looks at you and says, “Fuck you,” it’s time to fight. A cop who doesn’t fight gives up his post for the guy coming after him.

You have said that a lot of these tactics started with the drug war. Do you think that if the drug war comes to an end in 10 or 15 years—not that it necessarily will, but fingers crossed—

By the way, I am a little optimistic. I think it is ratcheting down from its extremity. I think it is happening now. Which is why I care so much about the optics of what happened in Baltimore.

Say more.

What?

Go on, I mean.

Guys saying, “Hands up” or “I can’t breathe” and shaming the country in some fundamental ways where we start to reassess this dynamic: That to me is incredibly powerful and essential. Ambushing a cop in Ferguson outside a station house, several months ago, is not good. People marching to demand on city hall accountability is incredibly good.

Listen, look up the governor of Georgia, a red state. He is closing prisons and releasing nonviolent offenders. If it is happening in Georgia—and it is—then we have reached some sort of terminus. That doesn’t mean it has been completely rolled back or that there won’t be retrograde moments. But the overreach of this thing—with 2 million people in prison—has finally registered.

And I assume you think there is a feedback loop. If this stuff leads to a ratcheting down of the drug war, then a ratcheting down of the drug war might lead to better policing policies.

At some point, when cops are not charged with enforcing an unenforceable prohibition, when you become an army of occupation, because this is an industry you cannot eradicate, and is employing so many people in areas of our country where real industry has disappeared, once they are not in charge of that, they might get back to the job of actually protecting a neighborhood, even a poor neighborhood, which they have never done. They let the ghettos police themselves. It creates an incredible dystopia. Look at Jill Leovy’s book Ghettoside. Her argument is that black communities are underpoliced. This seems to fly in the face of something like Ferguson, but both things are true. When they need cops to do their jobs, they are underpoliced, and when they don’t need cops to be battering into neighborhood, that is where they are overpoliced. Both things are true.

Did you read Ta-Nehisi Coates’ book?

Yeah.

You guys both have a lot of experience in Baltimore and talk about some of the same issues—

Not the same experience.

Certainly true. I think his book seemed more pessimistic about some of the issues—

I think it is more pessimistic. Listen, it is more pessimistic than my view and I don’t think I am ducking any critique here by saying that he’s earned that. To this day, knowing everything that police are capable of in my city and elsewhere, when a radio car goes down the street in Baltimore, I don’t feel pressure, I don’t feel eyes on the back of my neck, and I never will. I grew up a couple miles from where he did, and it just doesn’t matter. I grew up in a different America. He is entitled to a wariness that is earned. The most important thing he said in that book is that we—African Americans—cannot fix this. This is your fucking problem. It isn’t for us to fix. You may never fix it or confront it.

I would just disagree [with him] about the arc of progress. In my lifetime, I have seen a powerful growth in the viability and social and political import of a black and Latino and Asian middle class that is going to be reckoned with. We are going to reach a point where whites are a plurality and not an automatic majority in every political circumstance. There is a lot of growing up that the country can do behind that. Very quietly, out on the west side of my city, in the suburbs, there is a black middle class that is growing. And we are seeing things challenged correctly now. It is terrifying because everything is one step away from a very destructive riot, but at least it is being talked about and addressed. We are at a place we need to be.

[An HBO employee says that we have time for one more question.]

Might it be about Show Me a Hero? For fuck’s sake. [In jest.] We did just come out with a miniseries, motherfucker!

I was going to ask you about Martin O’Malley, but I guess I should ask about the show.

Yeah you should, you should. Everything I have said about Martin is self-evident. I have already said it.

What does this show address that you weren’t able to address in your other television work?

To again echo what Coates wrote, there are certain fundamental things about America that aren’t up to African Americans to fix. And what happened in Yonkers is what happened every time, everywhere a white majority is asked to share: to share geographic space, to share political power, to share economic viability. We are not very good at sharing in this country. In fact we are getting worse at it as the libertarian impulse gains traction. It’s really disappointing.

Even though what happened in Yonkers was a harbinger of political progress, the political cost was so astounding that there will still be people who look at it and say, “They shouldn’t have tried to do that.”

But this [status quo] didn’t just happen. Federal money was spent to hypersegregate our society, to make sure that the poor were shoveled into very small areas and that they would grow up in a different America. And when people say, “Well they shouldn’t try [desegregation],” it’s as if the last hundred years never happened, as if we are supposed to start from a magical—

Right-wingers love saying that. Starting now!

Yeah, let’s not speak to history, let’s not speak to intention, let’s not speak to federal money. Pay no attention to everything up until this point. Now we just have well-meaning white people and well-meaning black people, and some happen to be poor and some rich, and some happen to live in an America where everything is upside down, and the other half don’t. And let’s start from there and critique human behavior. It’s so juvenile. Being able to speak about what happened in Yonkers is very valuable to me.

As a well-meaning white person, thanks for doing this interview.

[Laughs]. Exactly.