I recently spent a decade developing a project that aimed to grow the repertoire of shorter compositions (“encore pieces”) for violin and piano. It involved 26 commissions and an open contest that drew more than 400 compositions. Amid all of that newness, I was drawn to go back to a pair of personally meaningful concertos from my more distant past, pieces that had extensive pasts themselves: Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 5 and Vieuxtemps’ Violin Concerto No. 4. As I threw myself into my work with living composers, and felt rewarded by the results, I could see that it does music no favors to consider only the newest works the most tantalizing. An artistic statement rarely emerges from a vacuum. It grows out of some kernel of inspiration that eventually becomes an individual creation.

The great value of what these days is called classical music is its span and reach. Over four centuries of influential composers, writing, details, concepts, and teaching have melded together into this winding, inventive, enlightening, divergent, derivative, and rebellious art form. We musicians can chart our lineages like family trees. How our teachers lead us, much like how our parents raise us, defines our earliest self-identities, whether we follow or reject what we are shown. Thus, while continuing to define my own trajectory, I felt a strong desire to take a look back at where I began and what formed my awareness of what I might be able to accomplish in my lifespan.

I didn’t invest much energy in the violin until the summer of 1985, when I was 5 years old. That’s when Klara Berkovich was the teacher in my group class at kiddie violin day camp. She had recently emigrated from then-Leningrad, and her style of teaching was brand-new to me. Nothing wishy-washy or overly enthusiastic: She was practical, very clear, and knew exactly what could be improved. She didn’t need to offer praise as motivation, which made me want to try harder, if only to hear her state her highest compliment: “good.” I came home very interested in taking private lessons with Mrs. Berkovich.

After a couple of meetings, she accepted me into her studio. I didn’t anticipate that she would lead me from that beginner phase through countless student recitals, to my first full recital (nearly an hour of music), to my admission into the Curtis Institute of Music, or that she would introduce me to musicians who would help shape my future career, all by the age of 10. But I knew I wanted to work with her every week. I soon got double that: two lessons a week, year round, without fail.

Starting with our first lesson, Mrs. Berkovich introduced me to the manifold particulars of violin technique and concepts of musical phrasing. However, great arts teachers don’t teach only the one discipline; they urge you to live fully, to gain enriching experiences and interpret your own creative voice, believing that your art is as much what you bring to it as what you do with it. Mrs. Berkovich was one of those teachers. She encouraged my love of reading and ballet. She showed me photos of visual-art masterpieces, advised me to think about music as stories beyond the notes, taught me to reassess habits that I took for granted, explained how to memorize and analyze the language of music, and gave me historic recordings. Mrs. Berkovich could tell that I liked challenges, so she assigned me violin homework slightly beyond my capabilities and guided me over the hurdles. When she demonstrated on the violin, I idolized those snippets of performance, and my goal was to someday play as well as she did. I also wanted to be as confident and thoughtful as she was. Standing barely 5 feet tall, her posture was regal.

The final big piece Mrs. Berkovich taught me was Violin Concerto No. 4 from the 19th-century Belgian virtuoso Henri Vieuxtemps. One of my favorite famous violinists had recorded it; knowing that I had big-scale repertoire in common with Jascha Heifetz thrilled me. Learning to play that concerto, with its grandeur, beauty, and emotional power, and acquiring the technique required to bring that music across, gave me hope that I might one day have a shot at becoming a professional musician. The seeds of widely-applicable wisdom Mrs. Berkovich planted in teaching me pieces such as the Vieuxtemps have grown with me over the years: “Every time you open the music, imagine you are seeing it for the first time.” “Never stop learning.” “You wouldn’t say something the same way twice; don’t play a phrase the same way twice.” “Always ask questions.”

At Mrs. Berkovich’s suggestion, when I was 10, I began looking for my second significant violin teacher. I found him at the Curtis Institute of Music: Jascha Brodsky. He was 83 years old and had a worldly manner about him, having studied with the legendary Belgian violinist Eugène Ysaÿe in Paris in the 1920s and consequently toured the globe for over 50 years. I found him fascinating. Mr. Brodsky wore three-piece suits, even in the summer, and a fedora when he went outside, and he smoked cigarettes till the ash dangled precariously. He had taught for six decades. I sensed that he would not tolerate his time being wasted, but I also could tell that he was caring and truly loved teaching.

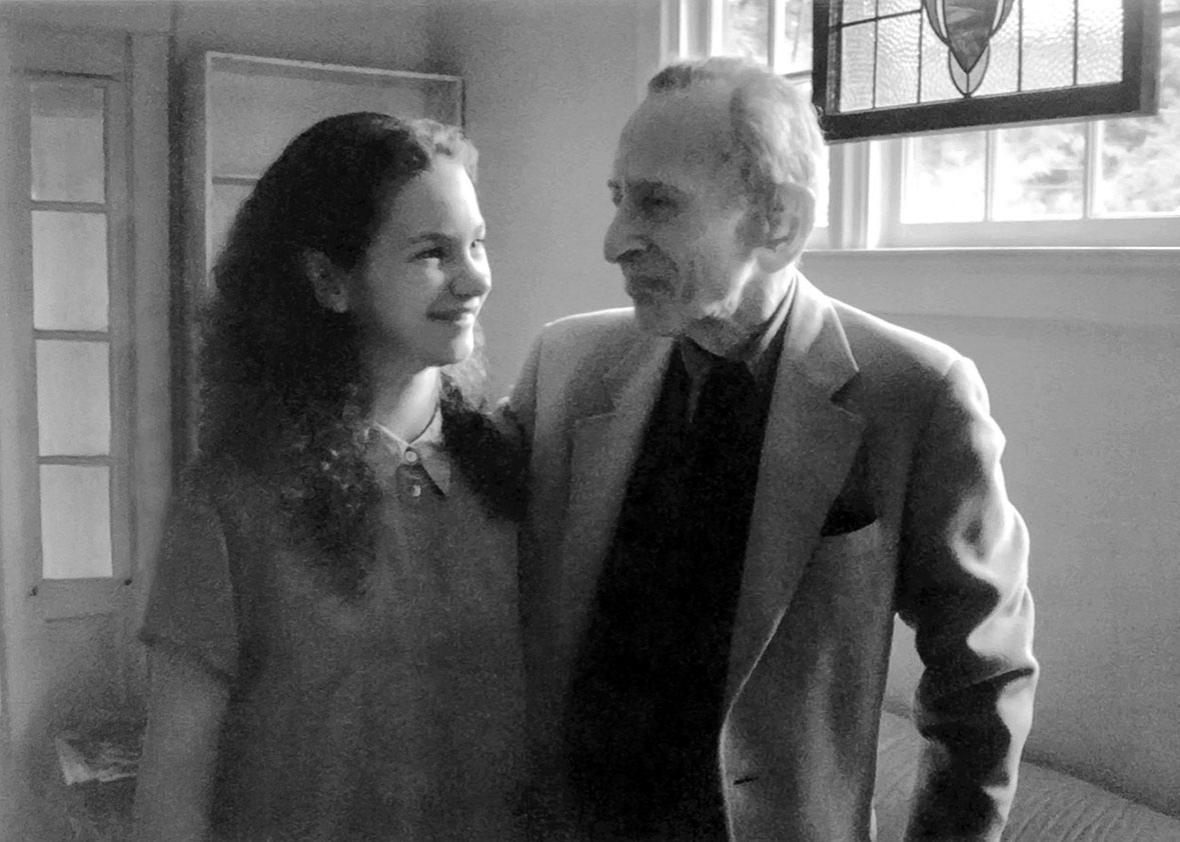

Hilary Hahn and Jascha Brodsky.

Photo by Stephen Hahn

The first big piece Mr. Brodsky assigned me was Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 5, a work performed frequently by many international soloists. When I thought of the great artists who had played the Mozart before me, and the traditions I was inheriting, my 10-year-old self couldn’t help but feel that, on some basic level, I’d arrived.

I studied with Mr. Brodsky for seven years. His tendency was to give me so much to work on at once that I couldn’t practice everything in a day, yet he wanted it all to be ready every week. I prepped constantly, which turned out to be good practice for life on the road. In our time together, Mr. Brodsky worked tirelessly with me to refine my technique and musical instincts, to build me into a more mature and nuanced violinist. It was not an easy process, but my repertoire grew by leaps and bounds and my playing improved noticeably from one month to the next. He didn’t believe in shortcuts: At 85 years old, he took it upon himself to learn a new concerto in order to teach it to me as well as possible. I had tremendous respect for him and his opinions. During breaks in lessons, while I rested my arms or took sips of water, Mr. Brodsky told anecdotes about his own experiences and about his colleagues, many of whom, due to the 73-year difference between our ages, I knew only from recordings. By sharing his past, he tied history to my life—including his musical history with Ysaÿe, who, coincidentally, had himself been a student of Vieuxtemps.

When Mr. Brodsky fell ill at 89, I visited him at a care center. Two nurses brought him to a large room, and he sat at a conference table. I assumed we were only there to chat, but I had my violin with me just in case. Sure enough, one of his first questions was, “Sweetheart, what did you bring to play for me today?” I reminded him of the repertoire I was working on, and he proceeded to give me a two-hour lesson. He leaned forward in his chair, singing examples, shaping my phrasing with interpretive gestures, and interrupting me to offer suggestions and corrections. For Mr. Brodsky, teaching was an unstoppable impulse. At the end of the visit, we said our goodbyes, and he kissed my forehead as he had done at the end of every lesson since I was 10 years old.

Three weeks later, I received the call that Mr. Brodsky had passed away. I was 17. It would take me a long time to come to terms with his absence, to figure out how to move on while still honoring his memory. Now, at 35, I look back on my years with both Mrs. Berkovich (who turned 87 in May) and Mr. Brodsky and am overtaken with gratitude. Without those two strong, kind, driven role models, and without their lessons, I would have certainly turned out differently. That might sound like a cliché, but to me, it is a palpable reality. The legacy that influential arts teachers gift their students is the encouragement to simultaneously create, inspect different facets of ideas, acknowledge gut instincts, and weigh opposing cues. They don’t like us to be on autopilot. They would rather we look with critical eyes at every scene, to seek the strange beauty in every setting. These techniques apply across the board, from music, visual art, film, writing, and theater, to dance, and beyond the arts as well.

My own recording of the Vieuxtemps concerto that Mrs. Berkovich brought to me and the first Mozart concerto that Mr. Brodsky taught me was released this spring. Through it, I reconnected with those two pivotal teachers in my life, offering a musical tribute to them and to the longevity of what they taught me, and reframing for myself the extent of their influence on me. It is difficult to feel like I am doing enough in that regard. They cross my mind every day. Thirty years after I met Mrs. Berkovich, it is still impossible for me to figure out where my teachers end and where I begin, and I feel very lucky to have had the time with them that I did.