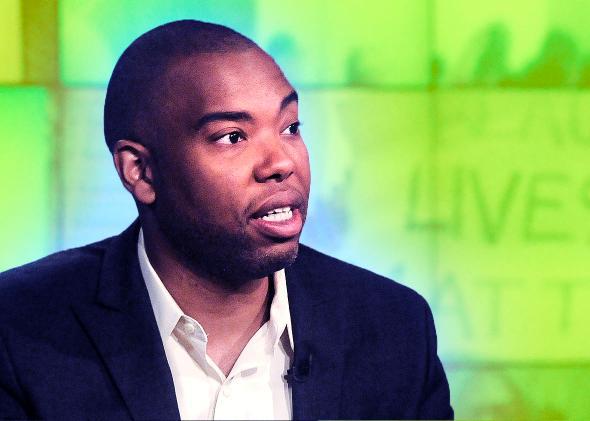

Ta-Nehisi Coates’ new book, Between the World and Me, takes the form of an open letter to the author’s son. In this short work, Coates focuses on the ways in which black Americans have been exploited and terrorized throughout American history. Like all of Coates’ work, it is passionate and occasionally angry, but tightly written and lyrical.

Coates has been writing about race at the Atlantic since 2008. Last year, his cover story making the case for slavery reparations became one of the most read pieces in the magazine’s history. Despite his argumentative approach to journalism, Coates is, off the page, soft-spoken and solicitous. He is adamant that he is a writer, not an activist, and seems slightly bemused by his giant following on social media and among opinion-makers.

We talked about the Charleston shooting, Obama’s forthcoming departure from the White House, and the legacy of To Kill a Mockingbird. The interview has been lightly edited and condensed.

If you look at the so-called conversation about race in this country, and in the media outlets that we read and write for, it seems as if the discussion is much more forthright than it was even five years ago. Do you think this is a sign of societal progress?

I think at places like Slate or the magazine where I work, there was a really poor record of hiring African-American writers. It was really that simple. And I think with the proliferation of the Internet and Internet media, it has been a little harder to maintain that gatekeeper position. It also used to be, in the 1990s, that a large number of African-American writers who wrote for places like the Atlantic and the New Republic were drawn out of the same social world. That was my impression. It was natural to reach to Harvard, to go to the Ivy League and find the smartest black person who would write the long essay. There is still some of that, but it isn’t as predominate. Jamelle [Bouie] went to UVA. Jelani [Cobb] went to Howard.

Your own career is interesting because I don’t know if your mainstream success could have happened five or 10 years ago.

That’s probably true. In fact I can tell you that is definitely true.

OK, so what’s going on then?

I can speak for me personally. For me, my writing benefits from my experience. I am better than I was 10 years ago. I have a better ability to say things that people say is quote unquote “radical” and evidence them. I was never much of a shouter but I have a better sense of how to do that. I think I just have a better sense. I started when I was 20. I am 40 this year.

At the same time as this racial conversation there has been one about gender issues and gay rights. The latter has been reflected legislatively too. Do you see this as being part of the same trend?

Well, I know marriage equality happened, and I know people think this is a particular moment, with the flag coming down, which is a real thing, but I don’t know that this is a moment. I am not convinced of that. What does my man say? “It’s too soon to tell.” [Laughs.] We are in the midst of it. I don’t really see any evidence. People might be reading certain things. You have an African-American president. Those are facts. You have a situation in which people have cellphone videos and people are recording acts by the police. But you are talking to someone who has known these things were going on for a very, very long time, so it’s hard to see this as a new moment. Prince Jones was killed 15 years ago. His mom has been thinking about that for 15 years. It’s hard to think of it as a new moment because people are now paying attention. It might be. I just don’t know.

Let’s talk a bit about Charleston. What did you think of the speed of the forgiveness that some of the families of the victims exhibited?

It is not my tradition. I wasn’t raised with that Christianity. I don’t know that I view it as inauthentic but I don’t know that I understand it. I do understand how hate eats at the soul and how to purge yourself of hate. But I also know that if you come into someone’s house of worship and kill their mothers and fathers and sisters, it is human to hate that person. You have a right to hate that person. And you have a right to work through that hatred. I think that sometimes gets lost when we talk about black folks with legitimate feelings. It is human. People get angry, people hate other people. If I was turned off by anything it was the comfort that people took in that forgiveness.

It is a huge theme on right wing talk radio. Aha, look, people can forgive, as if the rest of us shouldn’t be upset by this racist act.

Yeah. I don’t want to see it used as a club.

Your book is a lot about people who are victims of circumstance and history. Do you ever look at Dylann Roof like that, as a victim of history from the other side?

Sure I do. Dylann Roof is not the only person who bears responsibility. The Confederate flag represents an attempt to perpetrate a lie about American history, to bury the fact that half this country thought it was a good idea to raise an empire rooted in slavery. That is a part of our history. When you bury that history other people take control of it and use the flag for their purposes, and to ennoble their own hatred. Putting off the discussion allows the narrative of white supremacy. We really empowered that dude. It is very, very sad. But wait, I want to go back and make a point, it is a very important point and I want to make it as clear as I can.

I am going to edit it out.

[Laughs]. OK, you see these black folks who are disproportionately poorer and prone to crime and suffering crime, live in neighborhoods where it doesn’t appear that folks are keeping stuff up, and there is a steady background white noise saying that these people kinda deserve it, that they are lazier than you are, not as intelligent as you are, and when you receive some history about how folks ended up in that state you get two things: first, you’re told that it happened a long time ago, and second, that it has no impact on what it does right now. That’s a lie. That’s poisonous. That myth about black people is deeply tied into the Lost Cause. Nikki Haley says Roof perverted the flag. No, he correctly understood what it stood for. It stood for the right to take people’s bodies. We have a responsibility for the perpetration of that lie.

The history of the world is more powerful people repressing less powerful ones, whether it is men and women or colonialism. Do you think America is unique? Is slavery unique? Or is it our version of something every society does?

I don’t think it’s unique. I say that in the book. But pleading human error can’t really save America. We have no humility. We believe we are exceptional. That’s fine. But if that is the standard, then I have the right to hold you to that standard. We don’t go to Iraq saying we are doing what every country does. We are the deliverers of democracy. But this is a human problem.

Did your son read the book?

Yeah, several times.

Did he or your wife have any comments?

My wife helped me, as always, conveying the points I wanted to convey. We had conversations. I wouldn’t have done it if folks didn’t want me to do it. But everyone was pretty much pleased with what I came up with.

That’s what they tell you. Wait until I get them on the phone. I want to ask about corporal punishment. In the book, you ascribe its prevalence among blacks to the terror that the black community has suffered historically. I wasn’t certain about that connection. Is there a danger of ascribing too much to the past?

Well first of all, for most of human history people have hit children. The horror we have about hitting kids in America is certainly not shared throughout the world. So black people are not particularly original. But African-Americans are by and large, not wholly, Southern people. But in addition to hitting their kids more than whites at every socioeconomic level, period, they are just harsh on their kids, and I think in large degree that is a response to the fact that they know there is significantly less of a shot at a second chance. You can pay with your life. The consequences for black folks are so much higher. And I think folks are resolved to scare the hell out of their kids. Having said all that, and it’s important to say all that, I told my son recently, and I hit him four times, that if I had to do it again, I never would have hit him. I just wouldn’t have done it. It’s still violence. You are perpetrating the thing you are trying to get them to stay out of the way of. I was young when my son was born and I was scared as hell that he would wind up a drug dealer or in prison or whatever.

You are the subject of the cover story in this week’s New York magazine. The article points out that you recently suggested that maybe we should free everyone from prison. Do you say things like that to get the ball rolling, or do you really believe it?

Two things I will say: the first is that I was addressing the myth that lies behind a lot of this criminal justice reform, that if one just ended the war on drugs, we would somehow be OK. You have to think about violent crime. There is a dishonest conversation saying if we just let off some people who were caught with marijuana, we’d be OK. We have to think about it. Someone shoots someone at 20, should we let them out at 65? We have to think about that.

OK but how do you think of your role in the debates?

I don’t think about that.

You never think, “I have a huge following, a huge presence—”

No. No. No. No. Not at all. I am a writer. That is hard, going back to what we talked about earlier, why it is hard for me to assess a moment. I am distant from the process. To observe and speak and write as truthfully as I can. This is not false modesty. I came to the Atlantic in 2008. I was a formed person when I came. By the time the publicity started, I was like 36, 37 years old. I was comfortable with the idea of being a writer who went home and raised kids and had dinner with his wife. There is no reason to be different now. I am glad people are watching. It’s nice to see. But my approach—it would be very hard to shift it now.

What do you say to people who want to be activists? What should I, say—an educated white guy who thinks there is too much racism—do to make change?

Every person has to answer it for themselves. I could say, “go register voters” but you may not like doing that.

OK but I am wondering what you think needs to be done and how to do it. Is there something that you think is overlooked?

The obvious thing to my mind is the history. To be as conscious as possible of the history of the country you are living in. You should read up on the sociology. But I think that of every American. Beyond that, that’s a question for activists. It isn’t really how I come at it. Writing is a very solitary activity. It’s hard to tell someone to go do X, Y, and Z.

Do you know if the president has read the book?

I don’t.

We always heard about the effect a black president would have on black people. Do you think a black president leaving office will have some effect on black people? How will people respond?

Yeah, I think people are going to be depressed as hell. I think people are going to be depressed about Obama not being in office. I think in about five to 10 years the amount of sheer racism that Barack and Michelle and their children had to deal with will become evident. I think the fact that roughly half of a major political party believed he was either from Kenya or Muslim or needed to show his birth certificate will be seen as crazy. And not just crazy, but evidence of racism.

As opposed to now, when they seem sane.

The other day [Donald Trump] just declared it. I’m serious!

They’re batty.

It’s America. It’s always been batty.

How else do you think black Americans will react to Obama leaving office?

I think black folks know what this was. A painful, lovely, beautiful, once in a lifetime thing. I think they will be sad.

At least until the Ben Carson presidency.

Right, yeah.

What did you think of the Shani Hilton critique of your book, which seemed to argue it didn’t focus enough on black women?

I don’t know. I love Shani. I adore Shani. She is incredibly unique. But I think when books come out like this and get a great deal of hype, things are put on their shoulders. I am glad about it, but it gets freighted. I understand that it is the male experience and I am a male writing the book. I don’t know how to remedy that.

When books on big subjects come out, people often say, “Why didn’t it also cover this.”

But I think there is something beyond that. There are very few African-American editors in the industry. There is a paucity of representation, man. I think if we had many more African-American women with the opportunity to publish books like this, writing at the New Yorker and the New York Review of Books, we would have a much broader representation. So I understand it. I don’t completely agree with it but I got it.

What’s next for you?

I can’t tell you. Last time we talked I think you asked if I was writing a book and I couldn’t tell you. [Laughs]

What are you reading?

Barbara Tuchman, A Distant Mirror. 14th-Century Europe. Black Death. Excellent.

Summer reading.

My type of summer reading.

Speaking of books, any thoughts on Atticus Finch?

No. I have never read To Kill A Mockingbird.

Really?

I haven’t.

Wow. I think that will be the line from this interview people are interested in.

Why is that? People always surprised by that.

Uh, well—

Half the stuff that interested me, my white peers have not read. I am always surprised people are surprised that people haven’t read things.

You told New York that, “When people who are not black are interested in what I do, frankly, I’m always surprised. I don’t know if it’s my low expectations for white people or what.” Now people aren’t just interested—you are hanging out with largely white elites at places like the Aspen Ideas Festival. How do you understand that?

I don’t understand it. I am not messing with you. I don’t completely understand why people in Aspen want to hear what I have to say. But what you are doing here—and don’t take this the wrong way—is asking me to step outside of myself and look at myself.

That is exactly what I am doing.

As a writer I was shaped by a desire to write for black people. That things were not being represented. That was my motivating force. That it has become what it has become is shocking to me. I just wanted to be able to take care of my kids.