Gawker became famous for saying things that other news outlets knew to be true but didn’t have the guts to say. Celebrity X is a jerk. Executive Y cheats on his wife. These are the kind of stories that journalists share among themselves but tend keep from the public—but Gawker observed no such editorial discretion. As long as the story was true and it was a good one, Gawker would tell it. As Gawker Media founder Nick Denton himself wrote, the site was initially rooted in “the desire of the outsider to be feared if you’re not to be respected, nip the ankles till they notice you; contempt for newspaper pieties; and a fanatical belief in the truth no matter the cost.” This editorial fearlessness was Gawker’s best feature and occasionally its worst one.

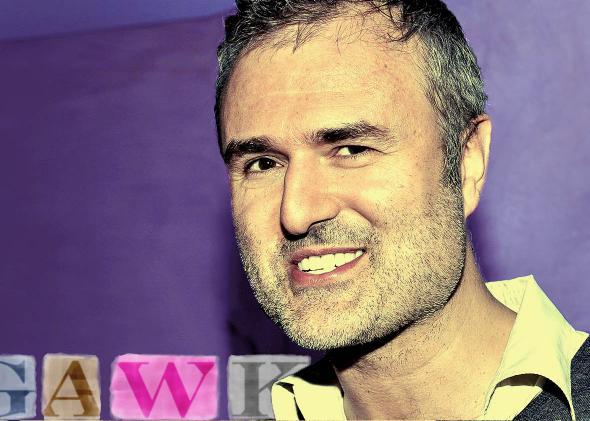

That Denton quote comes from a memo he wrote to Gawker Media staffers Monday, after two top editors resigned in a protest over editorial independence. The contretemps began last Thursday when Gawker published a callous and confoundingly unnecessary story alleging that a relatively obscure executive at a major media company tried to pay $2,500 to spend an evening with a male porn actor. It grew when Denton unpublished the story over his editors’ objections in a late bid at damage control. Monday’s memo was a bid to reassure staffers that Gawker isn’t in crisis while explaining to them what Gawker currently is. It is a remarkable glimpse into a media company that is struggling to reconcile its anything-goes history with a more circumspect present. And it seriously undermines one of Denton’s most enduring—and most self-serving—notions: that in the face of a legacy media that is hidebound and overcautious, Gawker Media is the last best hope for free journalistic expression on the Web.

Denton has long touted his blog network as an antidote to a cautious legacy media that allows its need for maintaining access and appeasing advertisers to affect its editorial decisions. In a December companywide memo, Denton dubbed Gawker Media staffers “the freest journalists on the planet,” and announced that whereas other media companies see their young readers as “a demographic to be traded by advertisers, capitalists and dealmakers,” Gawker Media journalists “think of them as individuals with interests as unpredictable as our own. We are beholden to no one. That is a precious thing.” In 2012, at the debut of the company’s Kinja blogging and commenting platform, Denton told Gawker readers that “fearlessness has always been the quality I’ve looked for in editors and writers,” and that Gawker articles and comment section discussions should be “full of the truths that are often unsaid and almost always unpublished in the established media.”

Sometimes Gawker’s truths manifested themselves as works of investigative journalism, sometimes as a celebrity sex tape. In October 2012, for instance, Gawker published an excerpt from a video depicting the wrestler Hulk Hogan in sexual congress with his friend’s ex-wife. Years earlier, Hogan had starred in a reality television series called Hogan Knows Best, which depicted him as a devoted husband and father; publishing the video seemed well within Gawker’s traditional mandate of exposing apparent celebrity hypocrisies. Hogan didn’t see it that way, though, and he sued Gawker for $100 million. Though it sometimes feels like the list of celebrities who haven’t sued Gawker is shorter than the list of those who have, Hogan’s lawsuit, unlike the others, has not gone away. It will soon come to trial, and if Hogan prevails and is awarded $100 million, Gawker Media could fall apart.

“Before you can think about it too much, just put it out there, just share it out there. I think that’s the essence of who we are,” Denton told the New York Times this June, in a profile pegged to the Hogan case. He has apparently changed his mind. Denton’s Monday memo essentially says that “just put it out there” is no longer Gawker’s operating philosophy. “Keep doing the great stories. Keep writing on the edge,” Denton tells his staffers in a key passage. “Just make sure you’re proud of it. Make sure people you respect can be proud of it.” This passage feels troubled for many reasons, not least because it is odd to think that Gawker has evolved into a media property whose writers are now supposed to be worried about the opinions of “people you respect.” Gawker’s editorial philosophy was always centered around the idea that very few people are worthy of respect and that its writers shouldn’t worry about being respected by the sort of people who weren’t brave enough to tell the truths that Gawker was telling.

But more to the point, “Make sure people you respect can be proud of it” could also be read as a euphemism for Don’t just casually write stories that could destroy the company. The last thing Gawker Media needs is another big lawsuit or ammunition for Hogan’s lawyers in their efforts to destroy Denton’s credibility. The Times quoted Denton as telling his employees of his fears that the Hulk Hogan jury might see them as “mean, bitchy Gawker bloggers run by someone who will probably be portrayed as a New York pornographer.” Thursday’s offending story about the libidinous media executive feeds into that unflattering portrayal.

To be clear, Thursday’s story was legally vetted prior to publication, and Gawker Media president and general counsel Heather Dietrick reportedly opposed Denton’s decision to remove it when he put it to a vote of the company’s managing partnership of top executives. The Gawker crew clearly believes the story was factually accurate, and it’s hard to win a libel lawsuit if the story you’re contesting happens to be true. But there’s more than one way to destroy a media company. The intensely unfavorable public reaction to Thursday’s story threatened to drive advertisers away from Gawker Media; in his memo, Denton claimed that keeping the post up on the site “probably would have triggered advertising losses this week into seven figures.” Last year, aggrieved video gamers joined together to persuade many corporations to stop advertising on Gawker in retaliation for the site’s coverage of the Gamergate scandal. The protest campaign ended up costing Gawker a reported seven figures in advertising revenue. Denton is clearly keen to prevent that sort of thing from happening again.

Putting aside questions of insulating journalistic decisions from business concerns, as a short-term risk minimization strategy, Denton’s decision to unpublish the story makes sense. Its long-term effects on Gawker Media might be more damaging. If Gawker is no longer the sort of place where its writers feel free to contravene media pieties in order to tell sometimes unsavory truths, then what is it? That’s unclear, but what we can already say is that by undermining his editors, Denton has hampered his ability to claim that his blog network is somehow more independent or different than the legacy media outlets whose pieties he claims to despise. The New York Times, for all its flaws, does not remove embarrassing articles just because they are embarrassing and might lead to lawsuits, or because people on Twitter think the story should have never been published.

On Monday, as part of his resignation letter, outgoing Gawker Media Executive Editor Tommy Craggs leaked the company’s new “brand book,” which serves to introduce Gawker to potential advertisers. In it, Gawker Media touts itself as being “fearless in sharing our own perspectives – regardless of how unconventional, unpopular, or unexpected they may be. We tell the real story.” Gawker Media has always been a company that prioritizes the telling of real, good stories. But in hastily publishing the media executive story, and then in just as hastily unpublishing it, Gawker Media has undermined its own story. On June 4, after the editorial employees of Gawker Media voted overwhelmingly to form a union, Denton appeared in his own site’s comment section and lauded Gawker Media as Internet’s foremost champion of the independent press. “In this age, we live as subscribers and employees of hollow conglomerates, and data points in the algorithms that govern the soulless networks that now dominate the web,” he wrote. “There is a haven for free thought. Only Gawker Media is independent. It is uncompromised. It is unique.”

Gawker can’t say that any more.