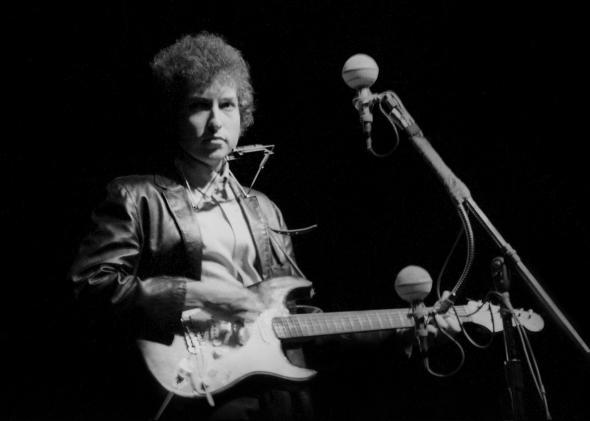

Fifty years ago, on July 25, 1965, the tousle-headed poet who had voiced his generation’s loftiest ideals of nonviolent protest came back to his spiritual home of many years, the Newport Folk Festival; strapped on an electric guitar for the first time in front of a band; and let loose a ripping sneer: “Aiiiii ain’t gonna wurk on Maggie’s fahm no mo’!” The congregation of folk music purists hissed, booed, threw bottles, and drove Bob Dylan from the stage, while the movement’s patron saint Pete Seeger had to be restrained from taking an ax to the power cables. And nothing was ever the same.

Or so goes the collective memory rock ’n’ roll cartoon that the veteran music writer Elijah Wald strives to turn back into flesh and blood in his new book, Dylan Goes Electric! Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties. The depth of Wald’s investigation may try some readers’ patience, but the book has lots to say about cultural memory and change—even if folkies make you roll your eyes.

These days, each passing calendar page seems to drag behind it a triplet of shadows: of the upheavals of the Civil War 150 years ago, World War I 100 years past, and the ’60s a half-century back. With each anniversary we’re reminded how much history persists within the present, even as closer examination tends to reveal received wisdom as a jumbled heap of broken telephone apocrypha. The tale of “Dylan going electric” is another one of those. Because history is told by the victors, rock lore holds up the Newport tale as the fierce nonconformist standing up to the timid crowd, but on a deeper level it was one nonconformity against another, a dispute about what it meant to rebel.

Using Newport’s archive of tape and film (some of which diligent searchers can find online), as well as his own interviews and secondary sources, Wald is able to reconstruct that weekend at Newport in almost moment-by-moment detail, as if reporting live from the scene. And nearly every moment disproves some piece of the legend.

Far from being driven from the stage, for instance, Dylan and band actually overstayed their allotted time, the closing-night showcase having been programmed to maximize diversity (and minimize idolatry) by granting tight 15-minute slots. Dylan was in the middle of the bill. There definitely was booing, but the most vociferous was about the shortness of the set. Others were responding to the uneven sound mix; only a minority were folk fundamentalists. (Still, since Dylan had never been received with anything but rapture at Newport, even a scrap of real hostility was news.) Also, nothing seems to have been thrown at the stage except in the solo acoustic encore, when Dylan asked for “an E harmonica” and a tinny rain of mouth harps clattered to the floor beside him.

And about Pete Seeger’s swinging ax? When Dylan was offstage looking to borrow an acoustic guitar, the evening’s host, Peter Yarrow (of Peter, Paul and Mary), tried to reassure the crowd, using musicians’ slang and saying, “He’s gonna get his axe.” Since Seeger’s distinctive voice had just been heard offstage complaining about the sound—and earlier that day Seeger had used a real ax on a stump as percussion for a logging work song (yes, you may eye-roll here)—some audience members put two and two together and got 5,000. So persistent was the fable that decades later even Seeger himself came to recall threatening to grab his hatchet.

No question, though, that Seeger was pissed. In public he said it was because of the volume. In private he said he felt betrayed. But it’s baffling exactly why.

By the time of that Newport gig, Dylan had already released the half-electric album Bringing It All Back Home and had hits with “Subterranean Homesick Blues” and the brand-new “Like a Rolling Stone.” Always uncomfortable with the “spokesman for a generation” role, Dylan had stopped writing overt protest songs much earlier. Wald quotes a bit of free verse Dylan had written on hotel stationery in May 1964:

HOW MANY TIMES

DO I HAVE t

REPEAT that

I Am Not A folksinger

before people

stop saying

“He’s Not A folksinger.”

In 1965 the new folk rock bands such as the Byrds were scoring hits with amped-up versions of Dylan’s songs (and soon Seeger’s as well), and his buddies the Beatles had “folked up” their style on Rubber Soul. Lennon-McCartney and Jagger-Richards were each writing ever more Dylanesque lyrics. (Dylan later would tell Keith Richards that Dylan could have written “Satisfaction,” but the Stones never could have written “Mr. Tambourine Man.” Mick Jagger agreed.) If he hadn’t gone electric, he’d have been outpaced by his own imitators. So why the surprise, really?

People also assume that Newport had never seen electric guitars before, but in fact black blues and R&B performers routinely plugged in, as had Dylan disciples Richard and Mimi Fariña that same day. The talk of the weekend before that night was the set by Chicago’s integrated and very loud Paul Butterfield Blues Band—the occasion of a slapstick fist fight between folk-world godfather Alan Lomax and the band’s (and Dylan’s) manager, Albert Grossman, who felt Lomax had been impolite in his introduction. In fact it’s unclear whether Dylan was planning an electric set before he got to Newport, but after picking up on the Butterfield band’s heat, he hastily recruited members for an overnight rehearsal as his backing group.

It seems mainly that Seeger got so irrationally irritated because, like almost everybody, he was smitten with Dylan but couldn’t keep up. In the four years since the former Robert Zimmerman from Minnesota arrived in New York, a baby-faced teen telling tall tales about his hobo travels and covering blues and Woody Guthrie, Dylan had turned the scene on its head several times over. He was a serial misbehaver. But that is also, Wald writes, “what Seeger had been”—it wasn’t long since the radical socialist had been blacklisted and briefly jailed—“and what Newport had celebrated.” Now, with Dylan’s latest zigzag, “It was not news that Dylan was the future; the news was that Seeger was the past.”

When Wald calls Newport 1965 “the night that split the Sixties,” he means in the sense that Dylan’s earlier career had taken place in that hazy prelude (lately recalled for us by Mad Men) when the establishment stood firm, the beatniks were in coffeehouses, and the big issues were civil rights and the bomb. The folk revival had represented a utopian answer to that age that was community-oriented and outer-directed, with its idealization of rural and “ethnic” authenticity—self-expression was worthwhile only in service of the cause.

As Wald chronicles, Pete Seeger had been raised in the old Popular Front left, discovered folk music out in America’s byways, and became its great disseminator. He had been a pop star in his own right in the 1950s (“the tall, slim Sinatra of the folksong clan,” wrote Billboard) with the Weavers, scoring chart hits such as “Irene, Goodnight.” Eventually he quit because the business required too many political compromises, such as toning down lyrics and accepting tobacco sponsorships.

The college-and-coffeehouse folk revival that followed had its celebrities—Peter, Paul and Mary albums, for instance, stayed near the top of the Billboard charts for months at a time, and ABC tried to capitalize with a weekly live TV series called Hootenanny! (which many, including Dylan, boycotted because it refused to let the dangerous Seeger appear). But most of these folk-crossover missionaries saw their role as elevating the tone of popular culture, a middlebrow mandate they related more to jazz or modern classical music than to commercial rock and pop. Its fan magazines, such as Sing Out, would debate the rights and wrongs of folk-singing, posing questions such as, “Can an All-White Group Sing Songs from Negro Culture?” (That’s an early version of an argument that Iggy Azalea and Macklemore, for instance, are all too familiar with today.)

Dylan, on the other hand, had been raised in the middle of nowhere, culturally speaking, and schooled himself on mail-order records and late-night radio. His heroes were disembodied, his Popular Front all in his imagination, and he did not want to pay tribute so much as to transfigure himself into their forms. In fact, before he could go electric, Dylan first had to go acoustic—he had been in bands with names like the Shadow Blasters and the Golden Chords in high school, playing Little Richard–style piano and some guitar, and only fully converted to folk during his brief stay in college. (One of the strengths of Wald’s book is that he regards Dylan as a musician first, everything else second, which his relentless touring in recent years testifies is no doubt the way Dylan sees himself.) Even between his first two folk albums in New York, he put out one rock-style single, though it sank without a trace.

Dylan was a music snob among the Greenwich Village folk scene, but he had energy for almost anything—Wald makes a good case that the main reason Dylan wrote so many protest songs was that the new Broadside magazine would publish them, and he never could resist a platform. But unlike Seeger, whose life made him a partisan of his ideals and his comrades, Dylan was loyal ultimately to Dylan. No doubt partly from having grown up an isolated Jew in the Midwest, he couldn’t stand others, including Seeger, Joan Baez, and his other folk-world companions, dictating who he would be. Rather than responsible middlebrow popularization, he would—just like the reprobates over at the Warhol Factory—go for neon pastiches of high and low culture, singing rhythm-and-blues about Beethoven, Ma Rainey, and the National Bank.

Wald points out that among Pete Seeger’s many other achievements, he was perhaps the most talented leader of singalongs in pop music history, sending the message that everyone else in the hall was by inalienable right an artist too. By contrast, everything Dylan has done, from his vocal mannerisms to his changes of style to his notorious rearrangements of his songs hits in concert, sometimes to the point of unrecognizability, seems calculated to destroy any possibility of singing along, at least for long. His songs belong to him.

In what Wald calls this “clash of two dreams,” it’s easy to see ways that Dylan’s individualist careerism was more conservative, or at least more pathologically American, than the folkies’ collective struggle. It wasn’t his “going electric” that bothered the folkies so much as his going pop, and his departure did fracture the movement. It’s become a cliché to call Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” snarl a precursor to punk, but folk was closer in spirit to what punk and postpunk would become, with its politicized wariness of corporate collusion and its do-it-yourself ethic. It was more hardcore.

Of course, cultural history was on Dylan’s side, at least temporarily. On his tours later that year and especially in England in 1966, crowds enthusiastically re-enacted the “going electric” ritual, booing and heckling and letting Dylan sarcastically reply. They loved the theater of it, and for a while at least, so did he—it made him Stravinsky standing up to the rioters against The Rite of Spring (another disputed legend). He was also on a shooting-star creative streak that saw him put out both Highway 61 Revisited and the double album Blonde on Blonde within the next year.

Meanwhile, the Vietnam War was taking over as a political issue; the civil rights movement was giving way to more militant black politics; and a counterculture on the more self-actualizing, subversive, and anarchically surreal model that Dylan represented was taking over from the Old Left and the old bohemia. Even Seeger eventually joined in and played with electric instruments from time to time. Yet as the counterculture made partly in Dylan’s image was slouching off to San Francisco to be born, its idol vanished.

For one thing, like John Lennon in the same period, Dylan was going through heroin addiction. For another, he was getting married and having children. But worst of all, his electric victory had put him back in the guru-and-prophet position that he could never stand. Like that other subculture-member-turned-superstar Kurt Cobain after him, he wanted out. Fortunately, he didn’t take it all the way, but he used his motorcycle accident in the summer of 1966 as an excuse to exit, a kind of symbolic public suicide.

After that, as Wald writes, “the Dylan who presided over what most of us remember as ‘the sixties’ — the Vietnam era, the campus riots, the summer of love, the hippies, the drug culture, the Weathermen — was truly a Zeitgeist, the ghost of a sacrificial Dylan.” He released records here and there but would not return to regular public appearances for eight years, by which time the revolution was over. He came back in the throes of divorce, singing more personal songs, in sync with the Me Decade. Then he would convert to evangelical Christianity in time for the Reagan era. He was never a weatherman, just pop culture’s most uncannily sensitive weathervane.

Meanwhile, for all the lip service critics and obsessives pay to Dylan’s sway, the folk revival’s legacy is robust too. Newport continued a few more years before it petered (and paul’d and mary’d) out, but kids continued to sing folk songs in classrooms and at summer camps, birthing the singer-songwriters of future generations—who would later play at a revived Newport Festival. (So would Dylan, but only wearing a false beard and wig—the guy doesn’t forget a grudge.) Today’s folk festivals welcome plenty of rock bands, even as they also appreciate singalongs and solidarity. And when Pete Seeger died in January of 2014, affectionate tributes came from every direction, not only for the saintly patriarch of the concert hall but for the radical firebrand who defied the House Un-American Activities Committee. So his reputation rebounded.

Traces of the ’60s “split” do linger in a general critical prejudice against music that seems too preachy or too earnestly mellow, too much like (as the common slam goes) holding hands and singing “Kumbaya.” But the larger reconciliation is that we’ve come to see that pop music itself, however it’s marketed and manufactured, is also inevitably folk art, a people’s form that registers unseen seismic waves. Is it really more radical for a white male artiste to sing of his restless alienation than for women, queer people, people of color, or poor communities to find music they can use to rally and celebrate and reflect themselves back? Maybe “Trap Queen” is the great folk song of 2015.

Dylan himself, in his senior citizen incarnation as living history, a kind of audible Illustrated Man, seems to gather every aspect of American music, pop or populist, into his late songwriting style. On his recent Shadows in the Night he croon-croaks his way through the Tin Pan Alley standards he once postured against, and that’s not even mentioning his album of Christmas jingles.

It’s difficult to picture a furor like July 1965 happening now. Artists can slide from rock to country to pop to R&B, to barely any grumbles. Maybe that means there’s not enough at stake in music now to merit a fight. Or perhaps it means that the contradictory cycle of counterculture and counter-counterculture that got spinning at Newport has finally been exhausted, and there are more urgent questions to ask. The kind of utopian vision that speaks to a more diversity-conscious, multiplatform generation may be to read less into genres—and applaud when artists go eclectic.