All week I’ve been thinking about Trainwreck, the hit romantic comedy I described in my review as feeling at once important and faintly disappointing. Its star, Amy Schumer, also wrote the script and worked closely with director Judd Apatow throughout the project, making Trainwreck Schumer’s debut not only as a feature-film leading lady but as a big screen co-creator of her own material. The movie feels important because of the way it highlights Schumer’s unique and potent skills: her gifts for both broad physical comedy and sharp, funny dialogue; her defiant embrace of not-always-niceness; the innocuous flat-voweled tone in which she gives voice to her character’s (and the culture’s) most humiliating truths. But that indefinable hum of accompanying disappointment—which for me has increased over a week-plus of reading and having conversations about the movie—derives from a sense that, as funny and original a summer rom-com as Trainwreck may be, Schumer’s film career could be so much more. Watching Trainwreck again, I found myself wondering what comes next for Schumer and how she might use those skills on the big screen to make the kind of crucial work her small-screen comedy shows she’s capable of.

Big screen, small screen—how long will these distinctions be worth making, now that our lives are a welter of screens within screens, all of them streaming content from the same five entertainment conglomerates? Well, for Schumer, size does still matter in one crucial way: Theatrically released feature films come in fewer economically viable formats than TV or online-only productions. On her Comedy Central sketch series Inside Amy Schumer, Schumer has the freedom to experiment and play: She can dance in a rap video; or make a commercial for a doll of herself; or do lots of things that aren’t starring in a rom-com where, at the end, she gets the guy. Over the course of three seasons, Schumer’s formal experiments have gotten ever bolder and funnier, culminating this summer in an episode in which Schumer remained almost entirely behind the scenes for the length of a 22-minute black-and-white 12 Angry Men spoof so flawlessly conceived that—even if it did air on basic cable with commercial breaks—it may well end up on my list of 10 best movies of the year.

By contrast, the narrative conventions of Trainwreck even at its loopiest seem a little constraining. The New York Times’ Manohla Dargis, who loved the movie, concedes that its lonely but monogamy-resistant heroine, also named Amy, is a “vanilla” version of the character Schumer often embodies in her stand-up or on her show, who is much more of—and I say this lovingly—an unrepentant drunken slut. (That Amy doll in the TV ad parody mentioned above? She comes with a one-night-stand partner set and has to be put to sleep on her side in case she throws up.)

But that gonzo party girl coexists with another recurring Schumer sketch persona: a woman so out of touch with her own desires she smilingly sacrifices her values, or her very life, on the altar of societal expectations. In “Cool With It,” Schumer plays an office worker so determined to prove to her male colleagues that she’s up for an all-in boys’ night out that she ends the evening alone in the woods, trying to remain chipper while burying the body of a stripper one of the men has accidentally strangled. Another sketch, “I’m Sorry,” includes Schumer among a panel full of women apologizing and “after you”-ing one another to a rhetorical standstill. Even as another of the panelists is dying from burns incurred in a freak accident (well, not entirely freakish—it all started because a man wasn’t listening to what she said), she continues to apologize as she rolls on the ground, spouting arterial blood from both legs.

These extrapolations of culturally approved female self-abnegation to the point of grotesque parody reside unproblematically alongside clips of Amy doing man-on-the-street interviews in which no question is off limits, or sketches in which her character’s affect is anything but retiring. Trying to shape this diverse population of Amys—astute social satirist Amy, not-afraid-to-be-a-jerk Amy, deeply insecure and desperate-to-be-loved Amy—into a coherent romantic-comedy heroine over the course of a two-hour narrative feature is, necessarily, an act of compression and condensation. As my co-host Julia Turner observed in our Culture Gabfest discussion of the movie, the Amy of Trainwreck—charisma bomb that she is—never quite makes sense as a character. She swings from painfully polite self-consciousness to callous disregard for others’ opinions and undergoes a third-act transformation that’s far more motivated by the narrative necessities of the genre than by any internal motivation. (Mild spoilers ahead, so skip the next paragraph if you haven’t seen Trainwreck.)

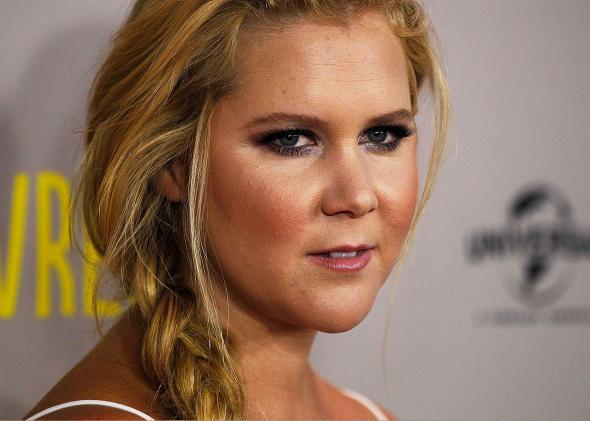

Photo by Brendon Thorne/Getty Images

Amy-the-character’s inability to completely master her final performance of stereotypically compliant femininity (even as Amy-the-performer nails the physical comedy of not mastering it down to the last hilarious microgesture) demonstrates to us, as well as to Bill Hader’s besotted sports doctor, that there’s something of her that isn’t captured by the romantic-comedy archetype of the woman changing to please her man. Still, the movie ends on the hardly fresh image of a reconciled couple making out in public while a crowd of approving onlookers applauds: the modern rom-com equivalent of one of Shakespeare’s multicouple weddings. It’s an ending that, like the movie itself, presents the unruly Schumer to a mass audience in a familiar frame—one that she already seems itchy to escape.

That mass audience has embraced Schumer to the tune of more than $61 million thus far. That’s a testament not only to Schumer’s talent but to the commercial wisdom of Apatow, whom I regard as a benevolent force in the world of comedy and an enormously gifted fosterer of young talent. But now Schumer—like James Franco, Jason Segel, Seth Rogen, Lena Dunham, and other writer/performers Apatow has mentored—is in the rare position of having the power to choose and shape her own career path. I hope she seizes the reins of her next big project, for whatever size screen it’s made, and makes sure it feels less like an attempt to fit her unconventional star persona into a familiar genre category and more like a full-length dive into the conceptually inventive worlds she explores on her own show. She doesn’t have to subvert the romantic comedy from within—she can ignore it entirely, create her own genre, and then subvert that!

In a recent New York Times profile of Schumer, Tina Fey said something great (as Tina Fey will do): “Women don’t exist only in relation to other women. … Amy is raising the bar for all comedians.” Perhaps the most radically feminist element of Schumer’s best work is that its go-for-broke formal ambition makes sidebar discussions about the gender identity of the creator seem even more irrelevant than they already did. In fact, some of Inside Amy Schumer’s most memorable segments, like that Emmy-worthy Lumet parody or a Friday Night Lights–inspired sketch about the persistence of rape culture, have barely featured Schumer as a performer at all—instead, she’s used a nearly all-male cast to spin out her own darkly funny fantasies about how misogyny operates behind closed doors. Notably, Schumer co-directed the (deliciously titled) 12 Angry Men Inside Amy Schumer episode with Ryan McFaul, seizing the auteur role even more clearly than she has in other episodes of the series. I heartily disagree with the Paul Giamatti character in that sketch that Schumer doesn’t belong in front of a camera. But I hope that for her next big-screen outing, Schumer will spend as much or more time looking through the viewfinder from the other side.