The first thing that must be said about the Rolling Stones’ 1971 album Sticky Fingers—which is being re-released this week in one-, two-, and three-disc editions, depending on how deep you want to wade into your own pockets and “previously unreleased” marginalia—is that it opens with the most morally vacant piece of music to ever hit the top of the charts. “Brown Sugar,” which in spring of 1971 became the Stones’ first U.S. No. 1 hit since “Honky Tonk Women” two years prior, is a rollicking and shockingly blithe rumination on slavery and sexual violence that unfolds over the greatest Keith Richards guitar riff that Keith never wrote (the riff, and the song, are Mick Jagger’s creation). The song’s Wikipedia entry describes it as “a pastiche of a number of taboo subjects, including slavery, interracial sex, cunnilingus, and less distinctly, sadomasochism, lost virginity, rape, and heroin” (quite a collection of links between those commas); in a 1995 interview with Jann Wenner, Jagger himself summed it up as “all the nasty subjects in one go.”

The second thing that must be said about Sticky Fingers is that it is one of the very best rock ’n’ roll albums ever made. A perhaps inadvertent effect of the “deluxe” editions is that they drive home just how perfect (and perfectly concise) this 10-track marvel is; the Stones got this one right the first time. The majority of bonus content on the extended versions is live material from 1971, which is predictably great, plus a small handful of “alternate” studio cuts that do little more than confirm their own superfluousness. Maybe there are people who’ve been walking around all these years just dying to hear different versions of “Wild Horses” and “Bitch,” but I’ve never met them.

Sticky Fingers may not be the most storied work in the Rolling Stones’ catalogue—it lacks the shattering reinvention of 1968’s Beggars Banquet, the Altamontian portent of 1969’s Let It Bleed, and the sprawling hedonism of 1972’s Exile on Main St. (these guys knew their way around some album titles)—but it’s the Stones at their most ferociously focused, during a time when their world was spinning apart. Sticky Fingers was released in April 1971, 16 months since the band’s last studio album, Let It Bleed; at the time this was the longest such hiatus the Stones had ever taken. It was the first collection of new Stones material to be released in the aftermath of both the Altamont disaster and the premiere of Albert Maysles, David Maysles, and Charlotte Zwerin’s groundbreaking documentary Gimme Shelter, an enormously controversial film that prompted accusations (most notably from the New York Times’ Vincent Canby) that the filmmakers and the Stones were profiting off murder. Expectations for the album were enormous and salacious—what will the Rolling Stones do next?—as though no one was sure whether they were musicians or provocateurs.

Sticky Fingers was a commercial smash, but reviews were mostly lukewarm. The New York Times wondered if the Stones were still “relevant,” then sniffed that “the verdict is still up for grabs;” Robert Hilburn of the Los Angeles Times conceded that it was “one of the best rock albums we’ll hear this year,” but then asked, “why is it so unsatisfying? One of the reasons is that it is mostly sound and little real fury.” Writing in Rolling Stone (no relation), Jon Landau took nearly 2,300 words to come around to the conclusion that Sticky Fingers sounded “detached” and suffered from “its own self-defeating calculating nature.”

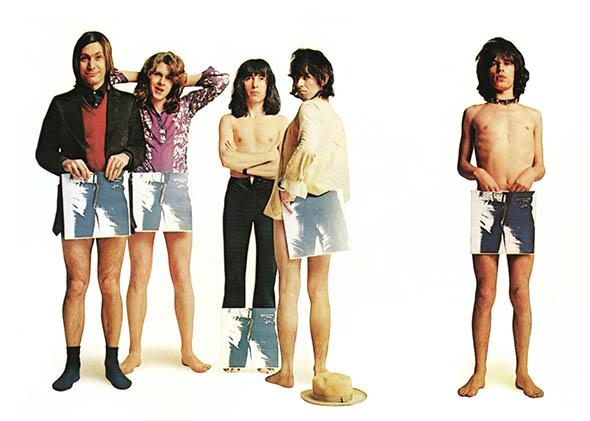

The Stones may have failed to meet expectations, but they did so in the band’s greatest fashion: defiantly and beautifully. Sticky Fingers was a misdirection, in hindsight the only livable option for a band outrunning its own Mephistophelean hype. The album’s cover—a close-up of a tight-jeaned crotch with a working zipper, designed by Andy Warhol—appeared to offer entry into a world of leering male sexual prowess, but instead offered entry into a world of something more honest and more interesting: male vulnerability. Written and recorded in the long wake of Jagger’s breakup with Marianne Faithfull and the early years of Richards’ torrid relationship with Anita Pallenberg, Sticky Fingers was a relationship record, an album about affection, pain, desire, loss, about loving people you’ve hurt and people who’ve hurt you.

The man most responsible for this was the most caricatured, maligned, and misunderstood Rolling Stone of them all: Jagger himself. Among a certain brand of Rolling Stones fan (I am one), blasting Mick is a favorite pastime: He’s the ham, the shill, the suit. In the mythology of the Jagger/Richards dyad, Keith is the perennial protector of the band’s soul, while Mick is that soul’s salesman. (Keith, it should be noted, has promoted this reading enthusiastically over the years.)

Sticky Fingers, though, is Jagger’s finest hour, starting with his songwriting. Jagger had long been a fantastic lyricist, as the wordy dexterity of songs like “19th Nervous Breakdown” and “Sympathy for the Devil” attested, but Sticky Fingers often found him working in more patient and mature registers, full of pithy imagery and careful, casual eloquence. “Sway,” the album’s second track, is a vaguely metaphysical love song to an unnamed woman described as “someone who broke me up with the corner of her smile,” a tender, beautifully evocative phrase. Or the half-resigned end of the first verse of “Dead Flowers,” “Well I hope you won’t see me/ in my ragged company/ you know I could never be alone.” The tiny emphasis on that last “you” is one of the deftest and funniest middle fingers to an ex ever extended.

And of course it’s not just what he’s singing, but how he’s singing it. By 1971 Jagger’s trademark mix of swagger and abandon had already made him the definitive rock frontman, and there’s no shortage of that here. The vocals on “Can’t You Hear Me Knockin’ ” and “Bitch” are absurdly charismatic and spectacularly musical: note the perfectly in-the-pocket faux hiccup Jagger slips in after the word drunk on the line “I’m feeling drunk/ juiced-up and sloppy” on “Bitch.”

Sticky Fingers also showcased Jagger’s startling range as a soul singer. “I Got the Blues” is a master class in slow-burn balladry, nestled against Charlie Watts’ best approximation of an Al Jackson Jr. backbeat, while the final verse of “Sway” is full-on gospel shout, fitting for a song about “that demon life.” And while the pristine guitars and honky-tonk piano of “Wild Horses” are straight country, the vocal is blues through and through—compare Jagger’s performance with Gram Parsons’ on the Flying Burrito Brothers’ “original” version of the song, released a year before the Stones’ own, and the difference is remarkable. Parsons’ pretty, careful vocal glides on top of the beat, while Jagger’s is ragged and laconic, the song’s famous chorus sounding less like celebration than tired and pained resignation.

Sticky Fingers ends with perhaps the strangest and most unique recording in the Rolling Stones’ entire catalogue, the haunting, modal epic “Moonlight Mile.” “Moonlight Mile” is an intoxicating mix of exotic and intimate, a song that builds a studied and stately distance, then collapses it with an immediacy as forceful as this band ever mustered. Jagger’s vocal drifts in and out of falsetto, his words stark and impressionistic: “When the wind blows and the rain feels cold/ with a head full of snow,” a line too pretty to be about drugs, which means it’s almost certainly about drugs. By the time enormous slabs of electric guitar start crashing into the track like thunderbolts, nearly 3½ minutes in, you’ve almost forgotten what you’re listening to.

And then we’re back to “Brown Sugar,” and you remember. In the 44 years since it came out, many have grappled with this song, so much so that grappling has become part of the lore. Robert Christgau called it “a rocker so compelling it discourages exegesis,” a masterful critical throwing-up-of-hands if ever there was one. More recently Lauretta Charlton penned an impassioned, if qualified, defense of “Brown Sugar” for Vulture. Is “Brown Sugar” a great song? Yes. Is “Brown Sugar” an inexcusable song? Also yes. But a lot of bands have made excusable music; only one made Sticky Fingers.