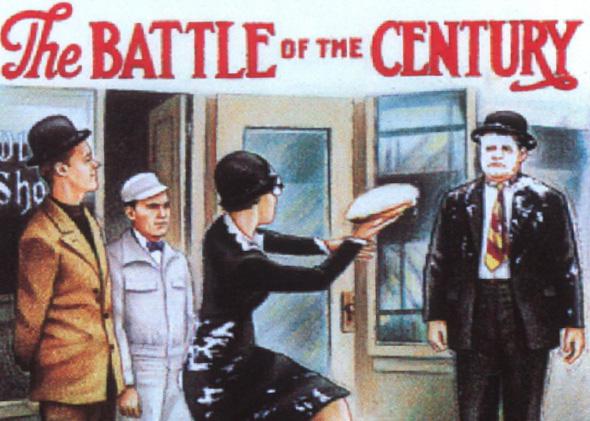

Over the weekend, it was quietly announced at the Library of Congress’ festival of “unidentified, underidentified, or misidentified films” that one of the most deeply mourned lost treasures in film history has reappeared. As reported by Pamela Hutchinson at Silent London, silent film historian Jon Mirsalis unexpectedly rediscovered the second reel of Laurel and Hardy’s 1927 film The Battle of the Century, lost for 60 years. The Battle of the Century is not only a crucial film in the careers of Laurel and Hardy, but it contains the biggest, best, funniest execution of the pie-in-the-face gag in cinematic history. For fans of early film comedy, this discovery is roughly the equivalent of Moby Dick swimming ashore carrying the Holy Grail.

Film historian Anthony Balducci has traced pie throwing on film back to at least 1905, but the Keystone Studios, remembered today for its eponymous cops, ran the bit into the ground in the 1910s. When Buster Keaton started making his own features in 1923, he explained in his autobiography, he forbade pie jokes entirely. But four years later, in September 1927, a virtual unknown named Stan Laurel proposed to revive the gag—by making it bigger than it had ever been before.

Both Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy had been appearing in films throughout the 1920s, occasionally together, but had only been officially paired together since that June. Although they’d shot the first three Laurel and Hardy films, none had yet been released. Nobody at the Hal Roach Studios knew it at the time, but they were at the center of a unique confluence of cinematic talent: not just Laurel and Hardy, but directorial legends Leo McCarey, George Stevens, and Clyde Bruckman. McCarey and Stevens had their greatest successes ahead of them; Bruckman, the most successful of the group in 1927, hadn’t yet begun his spectacular implosion. The first reel of the new feature seemed like a surefire hit: a parody of the Jack Dempsey and Gene Tunney “Long Count Fight,” which had just happened in September of 1927. No one had any particular reason to believe Laurel could pull off the tired pie throws he planned for the second reel. But he had an improvement in mind, as Philip K. Scheuer explained in a Los Angeles Times profile two years later: “His method would consist, simply and directly, of throwing more pies. Not one, not two, not ten or twenty, but hundreds, even thousands.”

It took some political infighting, but Laurel eventually sold Hal Roach on the idea. The studio bought an entire day’s output of the Los Angeles Pie Co. and, that October director Bruckman staged the greatest pie fight in history: 3,000 pies soaring gloriously through the air. And yet the secret of the film’s success, as Laurel told Scheuer, turned out to be not volume, but pacing:

“It wasn’t just that we threw hundreds of pies,” Laurel explained, “that wouldn’t have been very funny; it really had passed out with Keystone. We went at it, strange as it may sound, psychologically. We made every one of the pies count.

“A well-dressed man strolling casually down the avenue, struck squarely in the face by a large pastry, would not proceed at once to gnash his teeth, wave his arms in the air and leap up and down. His first reaction, it is reasonable to suppose, would be one of numb disbelief. Then embarrassment, and a quick survey of the damage done to his person. Then indignation and a desire for revenge would possess him; if he saw another pie at hand, still unspoiled, he would grab it up and let it fly.”

The Battle of the Century opened in December of 1927 and for a few happy months could be seen in theaters, randomly paired with anything from Lillian Gish’s “throbbing drama of love and sacrifice” The Enemy at the Hippodrome in Murphysboro, Illinois, to Henri Fescourt’s 1925 adaptation of Les Misérables—original running time 359 minutes—at the Bentley Theatre in Monongahela, Pennsylvania. In those days, when films left theaters, they were done: no revival screenings, no television, just a pile of prints melted down to recover the base metals. The last theatrical screenings happened in the summer of 1928, at the kinds of second-rate theaters that pointedly didn’t advertise air conditioning. Audiences who braved the heat were, with a vanishing few exceptions, the last to see The Battle of the Century in its entirety.

It’s not that the film disappeared from living memory so much as it passed into half-remembered legend. Pie throwing quickly became a cliché again, but those who’d seen The Battle of the Century agreed that it had once been executed perfectly. James Agee, Harold Lloyd, and John Ford all named it as one of their favorites, although they couldn’t agree on the title or director, and no one remembered the boxing match, just the pie fight. As Henry Miller (yes, that Henry Miller) put it, “There was nothing but pie throwing in it, nothing but pies, thousands and thousands of pies and everybody throwing them right and left.”

It wasn’t until 1961 that John McCabe published Stan Laurel’s account of the film, finally restoring at least a brief account of the film’s first reel. McCabe believed at the time that the film was “leading a lonely life in the vaults of the Hal Roach Studios.” But he was wrong—four years earlier, the negative had been exhumed for the last time by filmmaker Robert Youngson, probably the first and last person to see it complete since its theatrical run.

Youngson, who won several Academy Awards for his short films, specialized in compilations made with old stock and newsreel footage—daredevils, firemen, failed airplane designs, and the like. For his first feature, The Golden Age of Comedy, he was stitching together scenes from the silent film comedies and wanted The Battle of the Century’s legendary pie fight. He had footage transferred from volatile nitrate to safety stock—but, according to every report, only printed the specific footage he wanted, not the entire second reel. Once he was done re-editing it for his film, he threw out what he didn’t use. So when audiences were finally reintroduced to the film, it was with new cuts and wipes, and a hokey 1950s documentary voiceover.

Shortly after The Golden Age of Comedy was released, the Battle negatives decomposed so completely that they were junked. Only Youngson’s version remained—and he hadn’t printed the first reel at all. It wasn’t until the 1970s, when financier Earl Glick purchased the rights to the Hal Roach library before discovering Roach didn’t actually have copies of most of the films he’d just bought, that anyone even realized how much had been lost. To make good on his reckless investment, Glick funded a global search for prints of the lost film library, but there was no sign of the film’s second reel. In 1979, the first reel did show up: Now modern audiences could finally see the part of the film that contemporary audiences didn’t care about, but not the great pie fight of legend.

It turned out that first half was pretty good! The first reel is no 3,000-pie battle, but it’s surprisingly well-directed and funny. In fact, except for the not-yet-invented Vertigo dolly-zoom, the knockout punch that floors Laurel is remarkably similar to Sugar Ray Robinson’s in Raging Bull, though finding a direct line of influence from Clyde Bruckman to Martin Scorsese is a matter of conjecture. But that was all she wrote for The Battle of the Century; the second half was lost to history forever—just one of those second-law-of-thermodynamics things.

Screencaps courtesy of Image Entertainment

Until this weekend. All these years, a copy of the second reel was apparently sitting unnoticed in the personal collection of Gordon Berkow, a film collector and an amateur preservationist. At the time of his death in 2004 his collection included more than 1,400 prints, which eventually made their way into the hands of Jon Mirsalis in the summer of 2014. Mirsalis began slowly working through the canisters, cataloging and logging the state of each print and deciding which to keep and which to sell. Almost certainly destined for the sell pile: a canister labeled “BATTLE OF THE CENTURY R2.” Prints of Youngson’s edit were common—in fact, Mirsalis already owned one—and the complete second reel, as everyone knew, had crumbled to dust in the ’60s. Mirsalis only recently got around to inspecting the film, an experience he described over email. When he opened the canister, he found twice as much film as he’d expected wound around the reel:

… but sometimes Gordon had other things spliced onto a reel, so I didn’t think much of it. I put it on the projector and I see Stan and Ollie walking down the street. I assume someone is about to get hit with a pie, so I wait… and wait… and wait… and realize there is a whole set of gags playing out before we get to the pie fight. I’m figuring that my memory is just bad so I keep watching, we go through the whole pie fight, and then it’s the end of the reel. That’s when it hits me that I just watched all of R2.

The print in the canister had probably been struck for Robert Youngson during the production of The Golden Age of Comedy—Berkow, along with William K. Everson and Herb Graff, bought Youngson’s personal collection of prints. Mirsalis thinks Berkow made the same mistake he did, assuming Youngson’s print was of the edited version—everyone knew the story—and shelved it. For more than 50 years, it’s been waiting for someone who knew what he was seeing to project it.

Mirsalis is handing the film over to restorationist Serge Bromberg at Paris-based Lobster Films for preservation and an eventual theatrical or home video release. After nearly a century, The Battle of the Century may finally be seen again. But these occasional victories against entropy don’t just happen; without preservationists and collectors, The Battle of the Century would have disappeared forever. And for every film saved, more are well and truly gone. Mirsalis has his own list of lost films he’s still searching for: Lon Chaney in A Blind Bargain and The Chimney’s Secret, Ernst Lubitsch’s The Patriot, Josef von Sternberg’s The Case of Lena Smith, F. W. Murnau’s 4 Devils. When a film like The Battle of the Century miraculously re-emerges, it gives a sense that the teacup, despite what Hawking and Hannibal say, will occasionally reassemble itself. That’s sometimes true, but as every version of The Battle of the Century, no matter how mangled or incomplete, makes hilariously clear, the process is usually one-way: You can’t unthrow a pie.