It’s happened again. Brad Bird has released a new movie, and critics have declared that it harbors the messages of Ayn Rand. In the New York Times, A.O. Scott writes that the titular community of the movie is part “Atlas Shrugged theme park,” referring to the author’s magnum opus. Writing for New York, David Edelstein surveys the movie’s themes and finds “Bird’s Ayn Rand side showing its warty head.” North of the border, the conservative National Post concludes, “I bet Ayn Rand would like Tomorrowland just fine,” while the more liberal Globe and Mail headlines its review “Brad Bird’s Objectivist leanings shine brightest in Tomorrowland” and calls the movie “the most insidiously political blockbuster ever made.” Just about the only matter of contention seems to be the proper way to turn Ayn Rand into an adjective. Is the movie Randian (the A.V. Club, Metro, Flavorwire) or Rand-ish (Time Out London)?

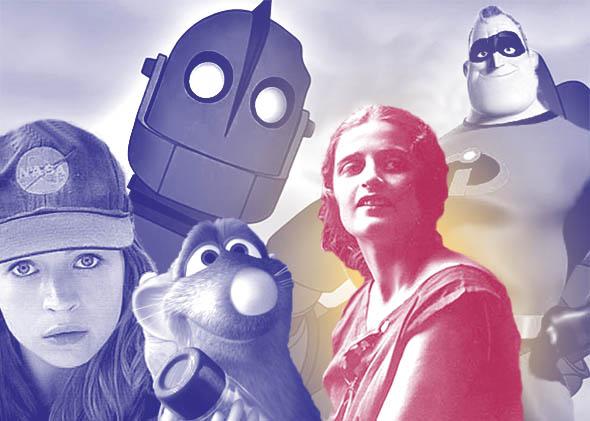

Critics were primed to hunt for signs of Galt’s Gulch, because they’ve seen them before. As Slate’s own movie critic Dana Stevens notes in her review, many critics discovered a similar subtext in The Incredibles, which she describes as “a barely disguised libertarian parable about the natural superiority of some individuals over others.” Back when that movie was released, this reading had a prominent advocate in A.O. Scott, who wrote in his New York Times review that the movie’s “central idea … suggests a thorough, feverish immersion in both the history of American comic books and the philosophy of Ayn Rand.” Meanwhile, a Guardian headline flat-out called it “propaganda.” We’d come a long way from the days when critics were calling Bird a Soviet apologist for The Iron Giant.

It’s a compelling theory—and I’ll confess that as I watched Tomorrowland, the name Ayn Rand went through my head, too. Like others, I was on the lookout—I remembered reading Scott’s Incredibles review, and I’d absorbed the conventional critical wisdom that Brad Bird is an Ayn Rand acolyte in Hollywood clothing. But in fact, the more you look into it, the more the notion that Brad Bird is Randian, or Rand-ish, is misguided. The lodestar of Brad Bird’s personal philosophy isn’t Ayn Rand. It’s Walt Disney.

To start with the simplest point: Brad Bird is no libertarian. Whenever he’s been asked about the perceived thematic similarities between his work and Ayn Rand’s, he has called the comparisons “ridiculous” and “nonsense.” Politically, he calls himself a “centrist,” and his Twitter feed shows which way he leans: In addition to being an outspoken environmentalist (something that’s pretty evident in Tomorrowland’s message about searching for hope in the fight against climate change), he is a vocal supporter of people like Jon Stewart, Stephen Colbert, Larry Wilmore, Hillary Clinton, and Elizabeth Warren—a senator who made her name with her attacks on libertarianism.

Of course, this doesn’t mean some Randian ideas couldn’t sneak their way into his movies, so we should take a closer look. To start with, it’s true that Bird’s stories (setting aside Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol, for which he didn’t write the screenplay) all center on characters who have special talents and are sometimes misunderstood by society, mirroring Rand’s interest in creating the Übermensch-like “ideal man.” In The Incredibles there are the “supers,” each with their own special abilities. In Tomorrowland there are people who are called “special,” apparently due to some combination of aptitude and optimism. In Ratatouille and The Iron Giant, the heroes have extraordinary abilities (cooking and gun-eating, respectively), but society attacks them because it doesn’t understand that they’re harmless. But where Bird really starts to make critics and many other viewers uncomfortable is where his movies seem to suggest that these talents—whether they be of rat or robot—are innate. As Slate’s own Dana Stevens puts it in her review, describing Tomorrowland’s special recruits: “Then he goes on to posit the existence of an Incredibles–esque race (class? breed? All possible words sound creepy!).”

Here it’s clarifying to take a closer look at Ratatouille—Bird’s fullest treatment of genius, and one of the movies’ most memorable depictions of an artist. Ratatouille, it’s worth remembering, is a movie about how geniuses do not come from any one class or race (or even species), and it’s a mistake to think that they do. The movie opens by setting in opposition the ideas of Chef Gusteau, whose famous dictum holds that “anyone can cook,” with the staunchly elitist stance of the curmudgeonly critic Anton Ego. To its credit, the movie’s message ultimately lies somewhere in the middle. As Anton Ego concludes in his final review, after his Damascene moment at the dinner table, “Not everyone can become a great artist, but a great artist can come from anywhere.”

That first part—that not everyone can become a great artist—is not what we’d like to believe. Most of us would prefer to think that hard work is the key to genius, which, as I’ve written before, is why so many were taken in by the provocations of last year’s Whiplash—a movie that only really makes sense if you believe that all genius requires is 10,000 hours of practice. But a growing scientific consensus shows that this just isn’t true—that it also matters how early you start, whether you’re in the right place at the right time, and how much talent you have in your genes. In other words, though most children’s movies would rather have us believe that anyone can do anything—and while I’d rather believe that I could become a three-Michelin-star chef if I worked hard enough—Ego was probably right.

Of course, this is not the only part of Tomorrowland that has rubbed critics the wrong way. It’s not just that the world of Tomorrowland has people who are special, it’s that these special people leave society for the creative community of the title—a place “free of the corruptions of money, politics, and power.” To many, this is where Tomorrowland begins to sound like Galt’s Gulch from Atlas Shrugged—the place where the novel’s brilliant Titans of Industry retreat and go on strike. But while on the surface the places may appear similar, Tomorrowland’s message about this kind of society is precisely the opposite of Atlas Shrugged’s.

The most obvious point of departure is that in Atlas Shrugged, John Galt is the hero, while in Tomorrowland, those who want to wall off the city are the villains. In Tomorrowland, the futuristic city is meant to be opened to the rest of the world when it’s ready, but Governor Nix gives up hope for the rest of Earth and insists instead on keeping Tomorrowland sealed off. In Bird’s words, it becomes “a gated community”; by keeping such a place “unspoiled … you spoil it.” George Clooney’s Frank Walker and Britt Robertson’s Casey Newton, in contrast with Nix, bring new recruits to Tomorrowland only because—as we see in the last scene—they want to send these dreamers back out into the world to make it a better place. And this points to the largest difference between Bird’s movies and Rand’s twisted novels: Rand’s stories are always about always pursuing self-interest, while Bird’s movies, at their core, are always about people coming together and creating things for the benefit of others. Even in The Incredibles, the clearest example of Bird’s admiration for the exceptional, those superheroes use their powers to help mankind. That’s what makes them superheroes!

And while many see Rand’s hand in Bird’s stories, Bird is more likely drawing from his own life. After all, if you know Bird’s biography, you know that the idea of a community of artists and innovators who recruit dreamers when they’re only teenagers is, to him, more than some naïve fantasy. Bird became obsessed with animation at a very young age, finished his first animated film at age 13, and at 14 sent it to Walt Disney Studios. The company saw something in him, and within a year he was apprenticing under one of Disney’s legendary Nine Old Men, Milt Kahl, who had helped create such icons as the title character in Pinocchio. A few years later, Bird was given a scholarship to the California Institute of the Arts—the school Walt Disney founded for dancers, composers, actors, artists, writers, and animators to come together at “a place where there is cross-pollination”—and he’s inserted references to the classroom where he studied (A113) into every movie he’s made since.

In this way the real key influence on Bird has always been hiding in plain sight. You might think the residents of Tomorrowland resemble Rand’s selfish Titans of Industry, but really they’re more like Disney’s Imagineers, or those animators at A113 and Pixar. (In an animated sequence cut from the film, we see the residents of Tomorrowland seated in rows drawing on drafting boards.) Tomorrowland might look like Galt’s Gulch, but it’s really more like Disney’s own utopian visions, for Disney, CalArts, and (perhaps most obviously) for the original EPCOT, the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow—a futuristic city he never finished but that helped inspire elements of Disney’s Tomorrowland attractions.

Of course, many of the arguments against Tomorrowland’s message had more nuance than I have the space to summarize here. (Just to start with, many qualified the “Randian” accusation with “vaguely” or “mildly,” which is closer to fair.) But the notion that his movies are covertly, “insidiously” Objectivist seems to have transformed over the last decade or so from a snowflake to a critical avalanche helping to bury one of Bird’s most imaginative movies. It’s fair to argue that Tomorrowland’s politics might be a little incoherent, or naïve. It is a kids’ movie, after all. But they’re not Randian.