Batman is a murderer. I’ve seen him kill with my own two eyes.

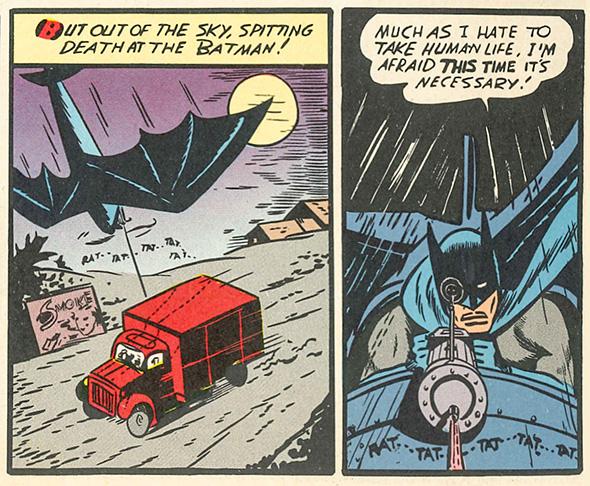

It’s 1940, and he’s piloting a propeller plane of his own design, painted black with its wings scalloped like those of his namesake, on which is mounted a powerful machine gun. Swooping down toward a truck, he opens fire on the nameless thugs in the front seats. They wilt beneath Batman’s rain of lead, losing control of the vehicle, which crashes into a tree.

Peppered as they are surely are with bullets, the miscreants may survive, but their cargo is not so lucky. It is a crazed colossus, an innocent mental patient mutated against his will by “an extract that speeds up the growth glands.” When the “monster” emerges out of the truck, Batman loops a “steel-like rope about his neck.” As he flies away, the creature’s now lifeless body dangles beneath the plane. This is only the start of Batman’s rampage. Dark as it is, the night is still young.

Courtesy of DC Comics

This, as an old comic book saying goes, is “not a dream, not a hoax, not an imaginary story.” No, this is “The Giants of Hugo Strange,” one of several tales included in Batman No. 1, a comic published 75 years ago, almost to the day. Arriving about a year after Batman first appeared in Detective Comics, the story was so gruesomely violent that it changed the course of comics history.

Few pop cultural storytelling tenets are more universally acknowledged than the idea that superheroes don’t kill. There are exceptions of course—grim anti-heroic outliers, generally—but for the most part our caped crusaders are advocates of a kind of controlled violence, willing to beat the snot out of their adversaries, but always stopping just short of the killing blow.

This mortal moratorium is central to the plot arc of the first season of the excellent new Netflix show Marvel’s Daredevil, which traces blind lawyer Matt Murdock’s journey from masked vigilante to the costumed champion of Hell’s Kitchen. He spends much of the season agonizing over whether to murder Wilson Fisk, the villainous property developer and crime lord known as the Kingpin, going so far as to consult with his priest, whose ambiguous advice—that evil “walks among us, taking many forms”—does little to resolve the dilemma.

It spoils nothing to say that Murdock ultimately refrains from killing Fisk. I say that it spoils nothing because his path is obvious from the start. His eventual embrace of a selective pacifism is as inevitable as putting on the costume that he dons in the finale, a costume that features prominently in the show’s advertising. We know he’s on his way to becoming a superhero, and becoming a superhero means learning to pull your punches. It’s meant that since 1940.

The first wave of comic book superheroes that emerged after Superman debuted in 1938 were mostly inspired by earlier pulp heroes, men of action, many (though not all) of whom were not afraid to take a life. Like the Shadow, on whom he was partially based, Batman sometimes wielded a pistol in his first appearances. He also was known to casually toss opponents off of ledges and otherwise actively send them to their deaths.

Batman’s penchant for violence did not go unnoticed, and “The Giants of Hugo Strange” proved to be a breaking point. After its release, letters from concerned mothers complaining about the story began to pour in to the offices of DC Comics. In his book Batman Unmasked, Will Brooker, professor of performance and screen studies at Kingston University, proposes that these notes had an almost immediate effect on the company’s editorial policy. Brooker reports that Frederick Whitney Ellsworth, then editorial director of DC, told Batman writer Bill Finger that Batman should “never … carry a gun again.”

Ellsworth was likely responding to more than parental censure. In May 1940, shortly after Batman No. 1 and “The Giants of Hugo Strange” made its way to the public, the Chicago Daily News ran an editorial by Sterling North attacking the nascent comics industry. Claiming that he had examined “108 periodicals now on the stands,” North concluded that comics would produce a “generation even more ferocious than the present one.” However ludicrous it may seem now, North’s critique hit home. Amy Kriste Nyberg, associate professor of communications at Seton Hall University, claims that the Daily News received millions of reprint requests for the editorial.

North’s brief, breezy screed named none of the titles that he surveyed. Nevertheless, Brooker makes a compelling case for the probability that many of North’s alarmed readers would have had “The Giants of Hugo Strange” in mind when his fears became their own. “It does not seem too far-fetched to imagine that some parents … picked up the first issues of Batman’s solo title” after reading the editorial, he writes. The machine gun–wielding monster they found within could have only amplified their concerns.

Scholars who trace censorship in the U.S. comics industry typically focus on the mid-1950s, when the psychologist Fredric Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent inspired a nationwide outcry about the medium. In a chapter titled “I Want to Be a Sex Maniac!” Wertham singled out Batman for special opprobrium, noting that the hero’s relationship with Robin “is like a wish dream of two homosexuals living together.” Thanks to Ellsworth’s editorial mandates 15 years before, Batman horrified Wertham primarily because he lived “in sumptuous quarters, with beautiful flowers in large vases,” not because he committed extrajudicial murders while piloting an unlicensed aircraft.

Ellsworth’s 1940 mandate reshaped more than the character who prompted it. At the time, Superman was similarly distant from his present self. A working-class crusader, he spent more energy battling war profiteers and slum lords than robots and super scientists. His proletarian values often led him into conflict with the authorities, making him an outlaw, if not an outright menace to civil society. Brooker claims that Superman was reined in shortly after Batman, remade into “a more unambiguously patriotic hero.” The company’s other titles were likewise brought into line, the rough edges of their characters quickly sanded down lest they once again inspire concern.

The industry as a whole didn’t adopt a collective set of standards until 1954, when prominent publishers banded together to form the Comics Code Authority in response to Wertham’s attacks and the congressional hearings they inspired. Long before, however, DC’s prominent characters provided a tacit model for every superhero that would follow. Accordingly numerous other costumed adventurers who refused to kill would appear in the years after Ellsworth laid down the law: Spider-Man wraps thieves up in webbing, the Fantastic Four banish their enemies to the Negative Zone, and Netflix’s Daredevil tosses would-be assassins into dumpsters. By editorial fiat, Ellsworth had effectively imposed a principle that comics storytellers still follow today, three-quarters of a century after the moral panic that inspired it.

To some extent, the rule has held because it makes sense. In an email, Brooker told me that Ellsworth’s strictures arguably enriched Batman. “Batman is a fascinating hero because of his position between boundaries,” he said. “I think his moral code is an important part of that tension, keeping him in that in-between zone where he will brutalize but not kill, employ martial arts against a mugger but not use a gun.”

A similar logic informs Daredevil, a logic so persuasive that it provides the show’s first season with its moral arc. “It’s important that Daredevil has qualms about killing,” Brooker said. “[He] is in the Batman mold, and the same reasons apply to him.” When Daredevil stays his hand, it may be about more than his Catholicism. The weight of comics history holds him back.