In the middle of Wild, book and movie, Cheryl Strayed meets a reporter on the road. He’s working for something called the Hobo Times, he says. She bristles at the suggestion that she is a hobo. In the book, she tells him, “Women were too oppressed to be hobos. That likely all the women who wanted to be hobos were holed up in some house with a gaggle of children to raise. Children who’d been fathered by hobo men who hit the road.” But the reporter is so entranced by the novelty of her act, he has no interest in her philosophies. He snaps a picture, brags about Harper’s, departs.

Here’s a hypothetical I’ve been chewing over ever since I read that scene the first time: Replace that reporter with Jon Krakauer, and Strayed with Christopher McCandless, the young adventurer about whom Krakauer wrote in his 1996 best-seller Into the Wild. How does the scenario change?

Strayed recently told Salon that she finds comparisons between herself and McCandless “sloppy,” but I think she’s understating how deep their common vein runs. Both McCandless and Strayed were twentysomethings tapping into a rich vein of Americana by seeking self-discovery in the expanses of the country. They were both products of a sort of crunchy anti-consumerism that feels very much of their era, the early 1990s. (McCandless vanished into the Alaskan wilderness in 1992; Strayed hiked the Pacific Crest Trail in 1995.) Both fumbled certain elements of the play, ending up ill-equipped for the challenges the wild had to offer alongside the beautiful vistas. And for both, literature was crucial to their understanding of their own experience: McCandless dreamed of Jack London’s world and Strayed parsed her grief through the verses of Adrienne Rich. They are twins, iconographically speaking.

Yet—and here’s where Strayed may be right to resist being classified with him—the cult of McCandless feels like a different creature than Strayed’s own considerable popularity. Both depend on the reader’s intense identification with the adventurer. But the process is different when the walker is a man rather than a woman, simply because in literature and pop culture and even just history, men have always been going into the wild. Women have not.

So McCandless evokes the romantic adventurer trope better than Strayed by virtue of having so many predecessors. He got to play-act Jack London, and Henry Thoreau on Walden Pond, and even the faraway Tolstoy, who complained in Family Happiness of “quiet life.” Sometimes, in his letters and journals, McCandless deliberately echoes the rhetoric of such long-gone Great Men. Totally separated from his family and his past, most of his ruminations on the nature of existence are pretty abstract:

The very basic core of a man’s living spirit is his passion for adventure. The joy of life comes from our encounters with new experiences, and hence there is no greater joy than to have an endlessly changing horizon, for each day to have a new and different sun.

You have to remind yourself, reading passages like that, that McCandless was actually writing this in the age of “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” not Goethe.

Meanwhile, Strayed couldn’t try to ape her ancestors in this way because, speaking from the perspective of gender, there hardly were any. Children’s literature, particularly at the turn of the century, has often tied young women to nature; the best example is probably Gene Stratton-Porter’s A Girl of the Limberlost. But, the occasional Isabella Bird aside, there isn’t something for adult women, as New York’s Kathryn Schulz pointed out last week. So Strayed’s book was a power move from the get-go; she cut women elegantly and deeply into the American tradition of popular wilderness adventure stories. This is not insignificant, giving women an alternative horizon to adventure on. It is the source of what Schulz called the book’s “kernel of genuine radicalism.”

And looked at that way there does seem to be an answer to McCandless, however unintentional, buried in the Hobo Times scene. You may recall of McCandless that when he set out on his journey it was as a radical break from his past. From Carine McCandless, his sister, we have recently learned that Christopher was fleeing not just an ordinary difficult relationship with parents; the McCandless household was darker than either Krakauer or Sean Penn’s 2007 film depicted it.

Yet there is something in McCandless’ complete cutting himself off from his family that feels like a male cultural province. The youthful Strayed displays the bluntness of the campus radical she once was by classifying all women as too “oppressed” by the obligation of care to become hobos. But she has a point; it’s no accident that women’s dreams did not so easily extend, before Wild, into solo journeys into the back country. Strayed’s adventure happened, to a great extent, because her own family relationships were severed, by her mother’s cancer and her own self-destructive impulses. It’s alone, not with her mother or her husband and not even with her friends, that Strayed manages to make peace with existence in the timeworn way of the American “wild” story.

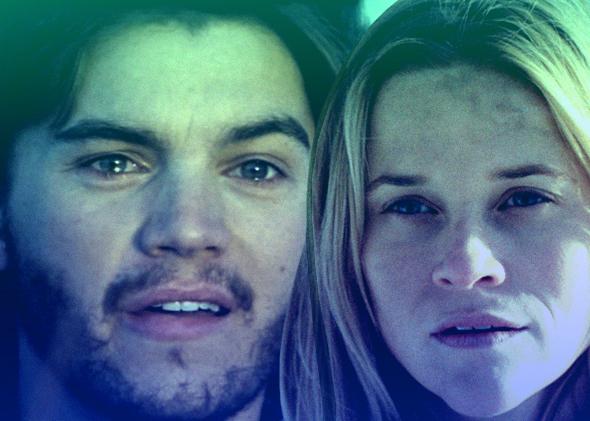

But Strayed did not ultimately choose to remain in solitude. Once you get to its last pages, to Reese Witherspoon on the bridge, Wild turns into a story about connection. The liberation Strayed ultimately comes to is an ending which ties her old, messy life into the new one she’s about to start. She links her past to the future:

What if I forgave myself? I thought. What if I forgave myself even though I’d done something I shouldn’t have? … What if what made me do all those things everyone thought I shouldn’t have done was what also had got me here? What if I was never redeemed? What if I already was?

And in the end she walks off the bridge into a life back in the real world.

That didn’t happen to Christopher McCandless, as you know. He died alone in a rusted-out bus in Denali National Park. His death note was a cheerful thing—“I have had a happy life and thank the Lord. Goodbye and may God bless all!” Perhaps, ultimately, whatever comfort he derived from the wild kept him there. Perhaps he wouldn’t have changed a thing. At the very least, if he had been rescued, he nevertheless seemed devoted to a life alone, one without the family who raised him or the “bourgeois” trappings of baby, wife, and a job.

So we have two paths to deliverance here. One finds solitude an end in itself, the other always a loop back to the world of people and obligation. People may respond to one or the other as a matter of temperament, of course. McCandless has plenty of fans undeterred by the fact that his story ends in death because they find his freedom so appealing. For anyone who detects a hint of bravado in his declarations about God and man, who detects a deep loneliness in McCandless’ rejection of just about everyone, though, Strayed’s got the better answers. Maybe that’s her real triumph: No one is ever again going to say that “wild” stories belong to men.