Three people from high school, two guys from college, a former colleague, and a woman you went to summer camp with can’t stop praising it on Facebook. Your Twitter feed is full of people raving about it, and it’s starting to fill up with other people teasing those people for raving about it. You’ve talked about it, in real life, with friends, acquaintances, and a stranger—they are all in its thrall. So is everyone in your office. Every website you read has an essay about it—and so, apparently, do all the websites you don’t read. (You know that because a girl from elementary school is studiously sharing each and every one of them on Facebook, too.) In a very brief period of time—a couple of weeks, a month, maybe two—it has gone from being something you had never heard about to something ubiquitous, beloved, critiqued, esteemed, dissected, adored, and compared, in a complimentary way, to crack (except in that one think piece, which said you really shouldn’t compare things to crack).

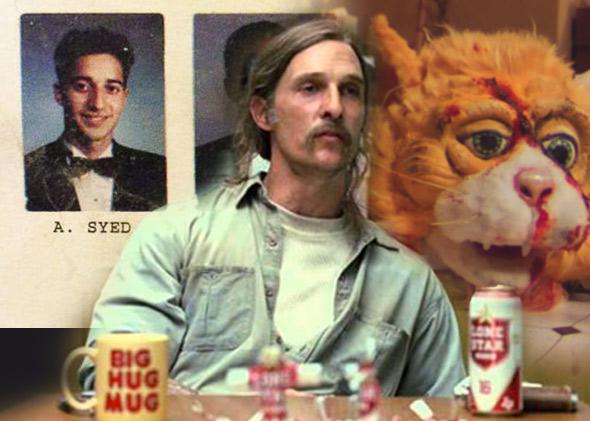

What is “it”? It could be Serial—unless it’s True Detective, the surprise album by Beyoncé, the first season of Girls, the last season of Breaking Bad, “Too Many Cooks,” cronuts, or any of the other crazes that have possessed us in the last few years. Though they feel like manias in and of themselves, they are all part of a larger fad: obsession itself. Serial may be so hot right now, but being obsessed with cultural product “X” is even hotter. Just check back in a month, when the Serial craze is over, as fleeting as all the rest, and we are losing our minds over something else.

But let’s start with Serial. Over the course of nine weeks the This American Life–produced true-crime podcast about the 1999 murder of a high school student and the perhaps-wrongful conviction of her ex-boyfriend has become a phenomenon, the most popular podcast of all time, downloaded weekly by well over 1 million listeners, pouring the friendly tones of host Sarah Koenig’s narration into their ears. But even though a podcast has never before inspired this sort of fandemonium, everything surrounding Serial, all the elements that make up the Serial-related experience, are familiar: the Reddit page, the think pieces, the in-jokes, the dedicated recaps (this time, they are podcasts themselves), the sense among early adopters that the phenomenon is already, in week 10, kind of over, and above all, the large group of discerning adults vociferously proselytizing with an abandon more commonly attributed to fainting teenagers about how amazing this thing is.

Humans have always been obsessed with things. Tulips and Twin Peaks and the Beatles did pretty well in their day. But adults used to obsess about things in a more steadfast manner, by having long-term interests known as hobbies. (Whatever happened to those?) Or they obsessed with downright stately occasionalness, when something out there really gripped the nation. Now we are engaged in a near-constant cycle of being “totally obsessed” with a cultural object (“obsessed” is the term of art on social media) and perpetually on the lookout for that next binge-experience. Why are we getting hysterically excited about very good but not hugely original cultural products seemingly every other month? Why have we turned into compulsive obsession-seekers?

As with nearly every aspect of contemporary life, the Internet has a lot to do with it. The Internet’s default mode is obsession. Nothing worth thinking or talking or writing about—nothing not worth thinking or talking or writing about, for that matter—gets thought or talked or written about in moderation. At the start, products like Serial or True Detective feel as though they are made inescapable not by their obvious and overwhelming clickiness—like, say, pictures of Kim Kardashian’s derriere —but by the force of good taste. There are things on the Internet that happen to us, but these are things that, initially, feel as though we made “happen.” And yet, at a certain point, the frenzy surrounding these beloved objects achieves the same level of inescapability as those naked pictures. Someone out there surely feels as annoyed by all the Serial coverage as someone else feels about Kim Kardashian’s tush. They have both become the latest obsession of “the Internet,” and you can either get on board yourself or get put on board, eyes rolling.

The silo effect of social media does something else with these obsessions: It makes them feel far more widespread than they are. Once upon a time, you obsessed with your friends, neighbors, people you could snail mail. Now you obsess with fragments of a much more extensive network connected to you through social media. The preferences of your Facebook friends or Twitter feed feel like persuasive evidence that something has caught on extensively. People you used to know better or don’t even know at all make for a sample population that seems so much more objectively random than your loved ones and the family next door. Yet in reality, this group likely reflects a narrowly selected demographic similar to your own. It only seems like everyone is obsessed with Serial because you are a yuppie and so are most of your social-media acquaintances.

Numbers bear this out. We may become obsessed more frequently than before, but our obsessions are narrower. Water-cooler subjects of decades past had far more reach than the water-cooler subjects of today. One hundred forty million people watched the miniseries Roots. Eighty-three million watched the conclusion of Dallas’s “Who Shot J.R.?” storyline. Thirty-five million people watched the first episode of Twin Peaks. Just 3.5 million people watched the finale of True Detective the night it aired. Fewer than 1 million people tuned in for the Season 1 premiere of Girls. Only 200 to 250 cronuts go on sale each day. The bar for what constitutes something “everyone” cares about is a lot lower than it once was.

The cultural fragmentation these numbers represent may help explain obsession’s appeal. If, as a culture at large, we have fewer things genuinely in common—because we’re watching so many different TV shows and streaming so many different songs and not watching movies in theaters—then those things that feel like mass experiences carry a rare frisson. We’ve gotten used to the thing we’re personally fixated on drawing blank stares from half the people we speak to. (“You spent all weekend watching what?”) When someone manages to get as big as Beyoncé, how can you do anything but ecstatically bow down?

Still, the cultural objects we obsess over are usually not the most popular ones. Big Bang Theory, with its 15-plus million weekly viewers, is a fixation for some; the Internet has well-stocked rabbit holes for everyone’s interests. But that show has never inspired the hysteria of a True Detective. Maybe that’s because Big Bang Theory doesn’t feel like a discovery. It doesn’t work as a signifier of taste—or not of good taste, anyway (which has surprisingly little to do with whether or not it’s actually good). Obsessed-over objects feel like they have arrived out of nowhere, unheralded or unappreciated. (“Have you heard about X? It’s amazing.”) This is true even when they are airing on the nation’s most prestigious cable channel. The Wire, with no respect from the Emmys and paltry ratings, was almost canceled by HBO before people started obsessing over it. Beyoncé arrived in the middle of the night; so did “Too Many Cooks.” Scandal was initially dismissed as another ridiculous soap opera. Serial is a podcast.

Having to “find” these objects is part of their appeal. You could adore Dallas, but with 83 million people watching it, you could not imagine that adoring Dallas was somehow particular to you, somehow a marker of your unusually good taste—your grandmother and your mother and your brother and Time magazine were nuts about it, too. But the things we obsess over now are things that we at least believe we have sussed out of the vast cultural morass. And if you have done the requisite cool-hunting to find these objects, then so has everyone else who loves them. Obsessions don’t just mark us as individuals with stellar taste; they signify our belonging to a particularly sophisticated cohort.

But when part of the appeal of something is that, suddenly, it feels as though it’s all everyone you like is talking about, then it doesn’t feel so great when everyone you don’t like is talking about it, too—when that website you try not to read is offering traffic-grabby posts about it, and that person you have spent the last decade finding inane on Facebook is suddenly sharing his (inane, obviously) opinions about it. Like the teenager whose favorite band gets popular, you may find your Serial obsession loses its shimmer when it turns out to be everyone else’s obsession also. Sure, Serial is very good—but is it that good? Hmmm. Maybe there’s something better coming up just ahead. Have you heard about X?