Serial listeners know Leakin Park. It’s where the bodies get dumped. “If you’re digging in Leakin Park to bury your body,” Baltimore residents told the podcast’s host Sarah Koenig, “you’re going to find somebody else’s.”

While the weekly podcast from the people behind This American Life breaks new ground in audio storytelling, it’s also letting outsiders in on a piece of old Baltimore lore. Serial is bringing up the bodies. Specifically, the bodies of Leakin Park, the West Baltimore wilderness where the show’s victim, Hae Min Lee, and dozens of other homicide victims were not so gently laid to rest.

Koenig is not the first storyteller to bring up the bodies of Leakin Park. In one episode of David Simon’s The Wire, detectives Bunk Moreland and Lester Freamon search the park for a body they might be able to pin on an up-and-coming drug kingpin. Freamon reminisces about a previous search in Leakin Park, where they were warned to only look for bodies matching the description. Otherwise, they were told, they might be there all day. The Baltimore mystery writer Laura Lippman, who grew up near the park, has put some of her (fictional) bodies there.

Like Simon and Lippman, who are married, Koenig was a reporter at the Baltimore Sun. So was I. When I joined the paper in 2000, most reporters had to take a turn on the night desk, usually under the tutelage of one David Michael Ettlin. A consummate rewrite man, Ettlin had an exhaustive knowledge of Baltimore ephemera. Three points became clear quickly: Most Baltimore cops pronounce it “Lincoln” even though it is L-E-A-K-I-N; you could pronounce it however you wanted but you better spell it right; and dead bodies often wound up in Leakin Park. Ettlin recently lamented to me that today’s murderers don’t care enough to wrap up the bodies in rugs and dump them in the park. These days, he said, they just leave them where they lay.

Recently, as my friends obsessed about Serial, I began to feel a strange ownership over Leakin Park. I was bothered by this perception that my city was—again—all about the bodies. But, if I was being honest, I had only visited the park once, and it was to ride the fabulous free trains with my locomotive-loving toddler. My job as an environmental reporter takes me into the woods a lot, but not those woods. Part of why I hadn’t been there more was convenience: In a city where everything is 20 minutes away, Leakin Park is a touch too far. But it was also fear: of the bodies, yes, but also of the great unknown urban wilderness.

In 1922, J. Wilson Leakin died and bequeathed several downtown buildings to the city he loved, instructing Baltimore to sell them, buy a wilderness park with the money, and give it his name. The city nearly bungled the gift, waiting too long to buy the land and then ending up in a costly court battle with the Leakin heirs when city officials instead wanted to buy several parcels for playgrounds. Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. pushed for the city to purchase the “exceptional” 243 acres along the edge of West Baltimore known as the Crimea Estate, which railroad magnate Thomas Winans had fashioned after he made his money building railroads in Russia.* That land was next to property the city already owned along the Gwynns Falls. The estate, situated on the unfortunately named Dead Run Valley, was “considered by all who viewed it as one of the very best bits of scenery near Baltimore,” according to Olmsted’s 1926 report.

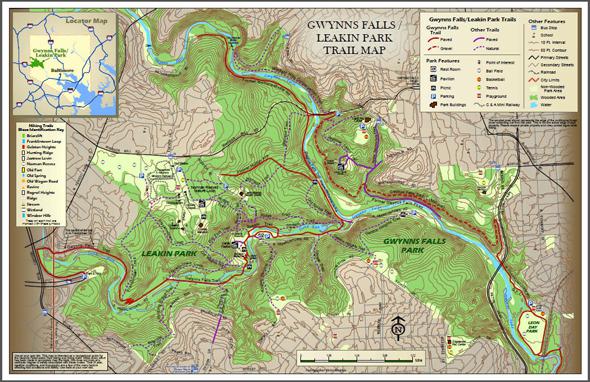

In January 1941, the city finally bought the land. It added dozens more acres in the coming years. Though Leakin Park and Gwynns Falls Park were two separate entities, they’ve become one contiguous 1,216-acre parcel. It now includes a 15-mile bike trail under covered bridges and across rocky gorges, a nature center, shaded hiking trails, and a restored mansion. It is larger than New York’s Central Park—indeed, it is one of the largest urban wilderness areas on the East Coast.

Map courtesy of Friends of Gwynns Falls/Leakin Park, Inc.

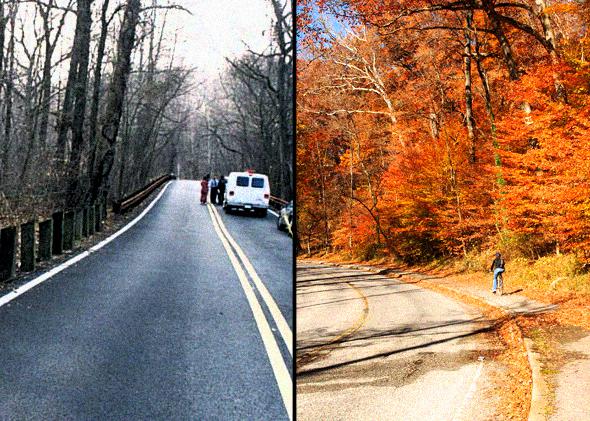

The park’s less savory reputation may have been sealed in 1968, when four young boys were found dead there. The following year brought up the body of Eugene Leroy Anderson, a Black Panther and possible FBI informant. Leakin Park’s attraction to Baltimore’s criminals comes from both its proximity to blight and its seeming remoteness from it. The park borders some of Baltimore’s most crime-ridden neighborhoods, like Edmondson and Walbrook. But it also touches Dickeyville, a quaint stone village known for its Fourth of July Parade. Franklintown Road and Windsor Mill Road bisect the park on their way from the county line to the gritty neighborhoods west of downtown. They can be convenient shortcuts when the Beltway is backed up during rush hour. But they can also be easy thoroughfares to get in and out of a secluded area after illegal acts.

When I asked David Simon whether the bodies of Leakin Park were more perception or reality, he referred me to the Bodies of Leakin Park, an exhaustive website created by software merchant Ellen Worthing. The site is part of Worthing’s larger efforts to build a database of all the city homicides. On the Leakin Park page, she gives names of victims, approximate location where they were discovered, and a bit of the circumstances surrounding their demise.

“I’m very good at researching newspaper archives,” Worthing said. When she began, she figured she might be able to collect the names of about 20 victims dumped in the park over the years. But “the list got longer and longer. Then I went up to the Pratt Library, and began looking in the microfiche, and that is when I realized it was going to be a lot more than 20.” Worthing’s research revealed 67 bodies found in Leakin Park since 1968. There are likely more, she said, because of a six-year gap in the Sun’s archives.

* * *

Molly Gallant is a Baltimore native who worked on outdoor programs in Alaska, then returned to her city determined to get Baltimoreans off the couch. Before long, Gallant had a job as an outdoor recreation programmer with the city parks department, taking locals kayaking in the polluted Inner Harbor, biking around city reservoirs, and hiking parks under the moonlight. Her co-workers applauded the boundary-pushing—until three years ago, when she organized an overnight campout in Leakin Park. Then, she said, they declared she was crazy. Even the normally unflappable Gallant, who was raised to believe Leakin Park was “somewhere you did not want to be,” began to wonder if she was pushing her luck.

“There were tons of jokes,” Gallant recalled. “Are we going to be that news story, 10 bodies found in Leakin Park?”

When they all woke up alive, Gallant decided it was time to get the rest of Baltimore in on the fun. She worked with volunteers to shut down access roads that, in Gallant’s words, “were screaming, ‘dump me here.’ ”

Those roads were always part of the park’s problem. The bodies of Leakin Park belonged not to unlucky cyclists, but to West Baltimoreans on the wrong side of drug deals, lover’s quarrels, accidents, or unspeakable deeds that happened, often, not in the park but near it. Lots of little access points made disposal easy; cutting off those routes and constructing a well-trafficked bike trail around the wilderness has made dumping less attractive.

On a recent Sunday, I visited Leakin Park with my husband and two children for the last train ride of the year. As my 3-year-old tugged at my hair and my 9-year-old fumbled through my purse for a banana, an energetic young man rode a bright blue bicycle along the line of enthusiastic kids, hoping to entice some of their parents to borrow bikes and explore the woods. I introduced myself to the man, a charming part-time parks worker and West Baltimore native named Jared Lyles, and told him I was thinking of biking the Gwynns Falls Trail the next day.

“It’s my day off tomorrow,” he said. “But if you don’t mind, I’d love to join you.”

My friend Eileen and I met Lyles the next morning at a trailhead next to the I-95 interchange near Ravens Stadium. He was too polite to mention that we were 20 minutes late. Two miles from the skyscrapers of Pratt Street, we felt as if we had entered the Shenandoah Valley. Amber and crimson leaves fell slowly in the breeze as we gazed across the Gywnns Falls valley. The falls rushed over giant boulders as we rode on the secluded paths, past old stone ruins and enormous trees, the city at once all around us and seemingly worlds away. For two hours, it was just the three of us, up and down the switchbacks, until the trail ended at the I-70 park and ride.

I asked Lyles about Serial. Turns out he’s a fan. (On the ride, he respectfully pointed out the spot where Lee’s body was found, near Dead Run.) Eileen, a Sun editor, asked about whether bringing up the bodies unfairly tarnished the park. Lyles said no. But, he added, they only tell part of the story.

Leakin Park is about the bodies, yes, but those bodies end up there because a city was and is willing to embrace a wild, wide space inside its boundaries. So Leakin Park is also about the elderly Koreans who gather chestnuts every fall, about the middle-aged black women who began playing tennis there after Arthur Ashe won the U.S. Open, about the truly outsider art gallery along some of the park’s trails. Leakin Park is about the grand Olmsted vision as well as the grimmer reality.

Real Baltimore is like that, too. The city is The Wire and The Corner and Serial, yes—but it’s also crab cakes, and peach cake, and a young city employee taking two women he’s just met on a ride through a park on his day off.

Correction, Nov. 17, 2014: This article originally misspelled the last name of landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted.