Excerpted from Eat More Better: How to Make Every Bite More Delicious by Dan Pashman. Out now from Simon & Schuster.

Every time you take a bite, you make important choices, whether or not you realize it. When you dip a triangular tortilla chip, do you hold one corner and dip two corners, or hold a straight edge and dip one corner? Your choice determines your maximum dip load, the ideal angle from which to enter the dip, and perhaps most importantly, the probability of chip breakage.

These choices matter. And often, they affect others. When that happens, we must seek ways to make the world a more delicious place for everyone. That’s the foundation of a civilized society.

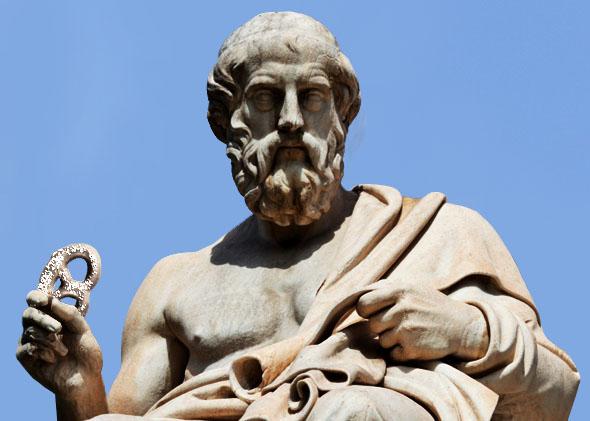

But how best to ensure deliciousness for all? Philosophers have long engaged in dialogues to answer questions like this one. Let’s take time now to study a dialogue between philosophers on the ethics of snack mix consumption.

Persons of the dialogue:

Socrates, who always wins

Thrasymachus, who is the Washington Generals of Socratic dialogues

Glaucon, who loves pretzels and is the host

Additional guests

The philosophers arrive at the home of Glaucon, who lives at the Port of Piraeus. He greets them warmly and puts out a large bowl of snack mix consisting of pretzels, peanuts, bite-sized bagel chips, and a square breakfast cereal made of crosshatched fibers, from which they all readily partake.

Socrates picks out a handful of peanuts and bagel chips from the mix, which draws Thrasymachus’ ire.

Thrasymachus: I see, Socrates, that you believe it permissible to cherry-pick your favorite ingredients from a snack mix.

Socrates: I do. Should I believe otherwise?

Thrasymachus: You should. The snack mix is a delicate balance of components. To target certain ones is to deprive others of the desired experience. It is unjust.

Socrates: So do you believe, then, that the purpose of a snack mix is to bring together ingredients in a prescribed ratio?

Thrasymachus: I do.

Socrates: And would it not stand to reason, then, that the Eater should compose each bite in that ratio?

Thrasymachus: It would.

Socrates: How then should the Eater ascertain the proscribed ratio?

Thrasymachus: Well, I think it plain to see, Socrates. Survey the mix and judge the proper ratio based on its appearance.

Socrates: But, Thrasymachus, do not different components have different weights, such that some components may be found in greater abundance at the top or bottom of the mix?

Thrasymachus: Most certainly.

Socrates: And is it not also true that the mix-maker’s technique may result in additional disturbance and ratio inconsistency from one stratum to the next?

Thrasymachus: It cannot be denied.

Socrates: So we agree that the proportions of the top layer are ever changing. Thus, is it not also true that Eaters will partake in different ratios at different points throughout the mix-eating process, and thus continually alter proportions further?

Thrasymachus: To suggest otherwise would be foolish.

Socrates: We are agreed, then, that it’s impossible to ascertain the precise ratio of mix components throughout the bowl, and that the ratio on top may not reflect the ratios beneath. Some might suggest that the mix-maker counter this concern by binding the ingredients into clusters of consistent proportions, but even Peloponnesians know that this binding would create a cohesive new food and not a mix. So do you agree that there is no way to impose bite consistency throughout an entire bowl of snack mix, even if it were desired?

Thrasymachus: I have no reason to speak contrariwise.

Socrates: Good. Furthermore, is it possible that, if I select only peanuts and bagel chips from a snack mix, I am shifting ratios closer to another Eater’s ideal?

Thrasymachus: Verily.

Glaucon [interjecting]: Indeed, I like pretzels and am less fond of peanuts. I do not object to the Socratic method, as it increases pretzel accessibility.

Socrates: Thank you, Glaucon. Have a pretzel.

[Socrates passes the bowl, and Glaucon is much pleased.]

Thrasymachus: Socrates, you are a sillybilly. What if I quite enjoy peanuts and bagel chips? I would consider it unjust to arrive at a snack mix to find all of those ingredients eaten.

Socrates: Well, Thrasymachus, a moment ago you agreed that attaining true bite consistency throughout a snack mix is impossible. Do you agree that if something is not possible, it should also not be preferable?

Thrasymachus: If not a shred of possibility exists, it is folly to prefer it.

Socrates: Well said. So the natural preference in snack mix consumption is for bite variety. Indeed, the ability to compose new and different bites throughout the eating experience is a central benefit of the form. The term “mix” refers to not only the method of preparation, but also the method of consumption. The very reason that components of a mix are never bound together is to offer the Eater a range of possibilities.

[Kant enters.]

Kant: Are you guys talking about snack mix?

Glaucon: But of course. Join us.

Kant: Equal access to and distribution of snack mix ingredients is a categorical imperative.

[Kant picks one of each mix component and arranges them in his palm Germanically.]

Kant: Subjective taste is irrelevant to this question, as it is to all issues of morality in eating. Perhaps, as you have said, Socrates, the natural ebb and flow of mix ratios is universally accepted and understood. But pure practical reason dictates that willful disfiguration of mix proportions is immoral.

[Just then, a voice calls from the bathroom. It’s Nietzsche. He’s been lying on the bathroom floor. Everyone thought he was asleep.]

Nietzsche: Oh, Kant, you’re always worried about the weak.

[Nietzsche stumbles into the living room.]

Nietzsche: The Eater is a great philosopher king! His drive to consume the perfect combination of snack mix ingredients is the true manifestation of the will to power. The Eater has no responsibility for the experience of the lesser being, who would sit on the Eater’s head like a dwarf and make it harder to chew! Besides, here we sit beneath a gateway. The name of the gateway is “This Snack Mix.” From the gateway, all snack mixes run backward for eternity. Must not whatever combinations can exist have already existed? And therefore, too, must they not be destined to eternally return? Thus, why should any ingredient be too precious to devour by itself or with others as the Eater alone deems fit?

Socrates: I can’t believe I’m saying this, Fred, but I don’t completely disagree with you.

[Suddenly Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau rush in.]

Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau [in unison]: Not so fast!

Nietzsche [groaning]: Oh great, here come Nasty, Brutish, and Short.

Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau [in unison]: We disagree on quite a number of details, but we agree on the basic notion that without some form of social contract, society cannot function. He who takes selfishly from the snack mix one day will be victimized by another’s selfishness the next. Eventually, society will spiral out of control and nobody will even make snack mix anymore, because they’ll know that as soon as they make it, it will be destroyed. When one eats snack mix, one implicitly enters into a social contract under which he gives up the freedom to cherry-pick ingredients in exchange for the freedom to partake of the bounty at all.

Glaucon: I wonder whether randomness has a role in this conversation.

Aristotle [bounding up the stairs into the scene and plunging his fingers into the bowl of snack mix]: Surely it does. Some events are unknowable. Snack mix consumption is a game of chance. You put your hand in and hope the odds are ever in your favor. … Oooh, bagel chips!

Socrates: What is the meaning of justice?

[The room falls silent. Thrasymachus drops a peanut.]

Socrates: Kant, you say that subjective taste is irrelevant, but in doing so you force the Eater to accept the mix-maker’s ratios, regardless of their merit, the Eater’s tastes, or the preferences of others. That’s not free, just, or reasonable. Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau, I’ve grown tired of your slippery slopes. We’re here in ancient Greece, walking around in bedsheets fashioned as garments, and yet even we can manage to create and share snack mixes from which many Eaters cherry-pick ingredients, without the fabric of civilization coming undone. Aristotle, if you consider snack mix consumption a random act, that is your decision. But the true Eater does not leave to chance that which can be made more delicious by choice.

[The room remains quiet. Socrates is on a roll.]

Socrates: Indeed, there is no greater justice than deliciousness, and the pursuit of that justice requires that one enjoy a snack mix to the fullest possible extent. Doing so means composing bites as the Eater desires them. The question here is, when cherry-picking is taking place, can all Eaters share equally in the benefits of just deliciousness?

I have no doubt that they can, and this leads me to my Theory of Snack Mix Forms.

Nietzsche’s analogy to the eternal path was not far off. There is only one true snack mix, the Great Snack Mix in the Sky, which flows endlessly through the vast trough of time. From that mix, every conceivable bite can be composed at once, and no ingredient is ever lacking.

But when we eat snack mix, as we have done here today, we partake not of that most pure mix, but of a particular representation of it. These representations may vary, but when we eat them, we are all seeking to know and taste that highest Form, that most delectable reality, the one true mix. Each snack mix experience is another step in the same endless journey, not a discrete moment in time independent of the others. As with any long voyage, some steps may bring you closer to your destination while others may bear less fruit, or pretzels. Some days you may arrive at a snack mix that has been cherry-picked to oblivion, but over time and with persistence, you’ll move ever closer to that Great Snack Mix in the Sky. Indeed, it is this most just pursuit of deliciousness that is the defining characteristic of the Eater.

[Socrates is finished speaking. The room is quiet. The only sound is Glaucon’s faint pretzel crunching. Thrasymachus blushes. Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau quietly put their hats on and show themselves out.]

Kant: You guys know how to get to Prussia?

Aristotle: I’ll show you.

[Aristotle and Kant leave together. Nietzsche returns to the bathroom floor.]

Glaucon: Let’s go for a walk, Thrasymachus. We’re out of pretzels.

[Exeunt.]

Excerpted from Eat More Better: How to Make Every Bite More Delicious by Dan Pashman. Out now from Simon & Schuster.