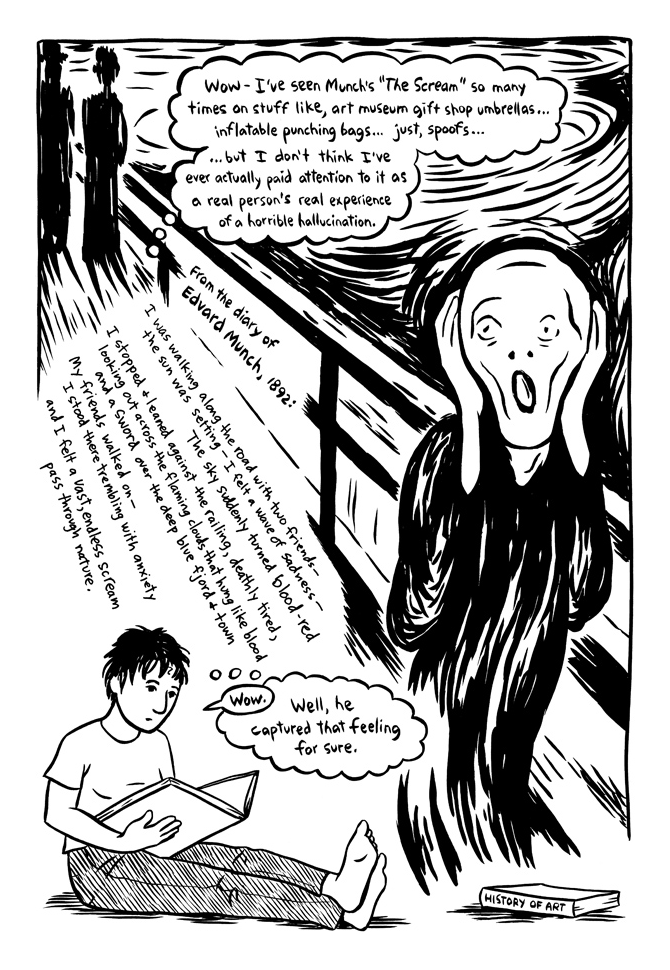

I’ve seen The Scream, that Edvard Munch painting of the ghoul with his hands framing his face and his mouth gaping, maybe a thousand times. But I had never read the accompanying diary entry from Munch until I got my hands on Marbles, by Ellen Forney. In a clenched scrawl, right below her own description of how unfamiliar they seemed, she reproduces the painter’s words:

Penguin Press

Something about seeing the text there and the image (ably captured by Forney) was an epiphany. It didn’t matter that both of these forms related an experience—a sound!—that neither could totally express. Now I think about the fierce synergy of those pages whenever the question of representing the ineffable bubbles up. The ineffable in this case being the darkly involute ways our minds can become totally effed.

One reason I’ve grown to love comics is that I cover a lot of mental health issues for Slate, and there is a rich vein of psychological unrest winding through the medium. You could argue that cartoonists are creating our culture’s best new representations of fragmented, hallucinatory, chaotic experience. From David B’s Epileptic to Darryl Cunningham’s Psychiatric Tales to Nate Powell’s Swallow Me Whole to Forney’s Marbles to Allie Brosh’s explorations of depression and Matthew Inman’s of compulsive exercise, mental dysfunction finds vivid voice and form in comic books. I don’t know if psychological illness is more prevalent in comics than in traditional words-on-paper writing—there is no shortage of mental disorders in the memoir section of your local bookstore—but comics seem particularly well-suited to telling these kinds of stories.

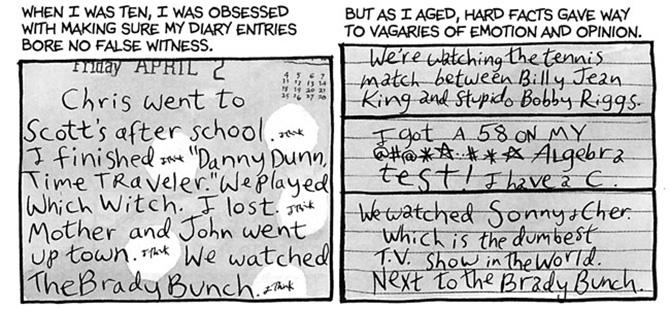

Perhaps it is just timing, the confessional rivulets still streaming from Plath and Lowell merging with an unrelated explosion in visual storytelling. But maybe a certain psychological profile also gravitates toward self-expression in cartoons. According to Princeton’s David M. Ball, editor for an academic series called Critical Approaches to Comics Artists, the form has long attracted “loners and misfits, the socially dislocated folks who don’t feel like they run with the varsity team.” Cartoonists are reclusive, or so the mythology implies. The demands of the job enforce isolation, quiet, and obsessive attention. “I think if you asked creators why they address mental illness so often,” Ball said, “they’d tell you it’s because they’re a little bit nuts.” He notes, of the beautiful way Alison Bechdel has chronicled her childhood with obsessive compulsive disorder, that it is hard to imagine a better re-enactment (and, perhaps, exorcism) of her painstaking impulses than the repetitive inking of minute versions of herself in hundreds of tiny squares. (See also: Justin Green’s Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, an OCD odyssey.)

Mariner Books

Ellen Forney, whose graphic memoir Marbles unfurls the story of a bipolar diagnosis and its aftermath, agreed that the theme of mental illness “is striking and present in the genre.” She cited a possible link between creativity and mood disorders: “To the extent that cartoonists are creatives, and creatives are more likely to have some experience with mental illness,” she told me, “it makes sense.”

Yet the genre’s preoccupation with psychopathology seems deeper, more in-the-grain. From a historical standpoint, comics have long radiated a disreputable, marginalized, and subversive energy. The underground comix of the ’60s and ’70s launched the careers of cartoonists like R. Crumb and Art Spiegelman, who inspired the next generation with lurid excavations of the cultural id. Crumb detailed sexual anxiety and drug use; Spiegelman, trauma and the Holocaust. “In addition to the allure of the twisted psyche, the romance of not belonging,” Ball told me, “comics creators adopted what you might call a ‘rhetoric of failure.’ ” It was a disaffected, pre-emptive stance that sought to rescue artists from the judgments of materialist society. You wore your commercial defeat like a badge. You were broke and insane. Not only did this “outcast” vibe lend cartooning a sheen of countercultural glamor, but it reflected a state of affairs as freeing as it was unprofitable: There were, in the comics world, no prize committees to impress, no grants to vie for. “You didn’t have to toe the line in terms of subject matter,” Ball explained. “You could do whatever you wanted.”

As awards judges began to send probes into the cartooning universe, that freewheeling mentality was threatened. (Giving propriety the middle finger/going long on your benzodiazepine regimen is easy when no one’s looking.) Maus won a Pulitzer in 1992. Later, the success of Persepolis—not to mention, later, flashy National Book Award nominations for Gene Luen Yang’s American Born Chinese and David Small’s Stitches—had New York trade publishers hurriedly buying up proposals for “graphic novels” from young cartoonists. (A lot of them flopped.) Still, Ball’s theory speaks to the persistent undervaluing of an legitimate artistic genre, one yet dwelling in the shadow of caped crusaders and lisping ducks. Childhood associations lend cartoons their ever-present goldenness, Ball says, but also their “taint of juvenilia.” When I first heard about the underground comix movement, I thought of Dostoevsky’s Notes From Underground, in which a marginal critic rails against society’s delusions and dictates. On one hand, the Underground Man is a crazed nut. On the other, the experience of madness is very much the experience of someone who is not being taken seriously.

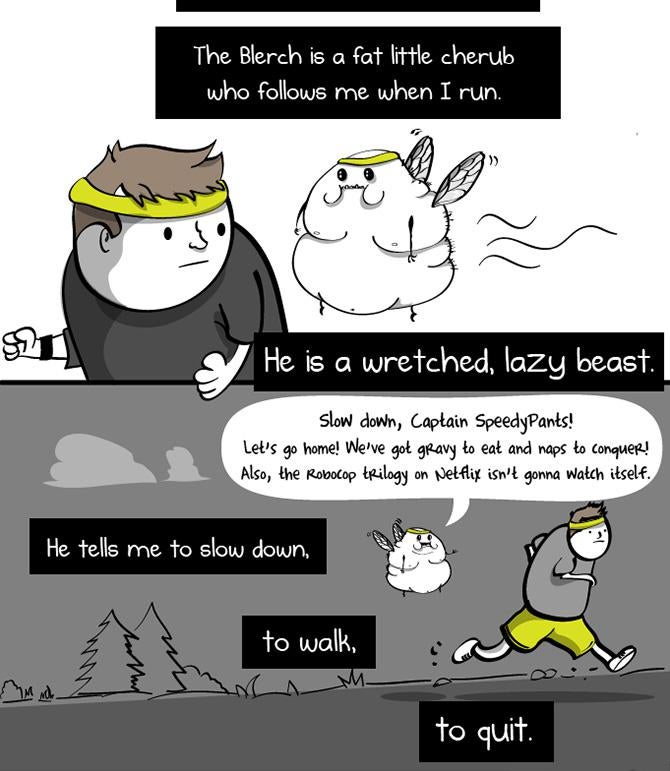

Matthew Inman

William Kuskin, a professor at the University of Colorado at Boulder, has a slightly different take on why comics excel in depictions of mental illness. “You can’t separate graphic novels from their superhero roots,” he told me. “That origin story—the broken protagonist who transforms himself—is the true meaning of the genre.” For Kuskin, comics are above all narratives of metamorphic identity: A traumatized Bruce Wayne puts on a costume in order to face external and internal damage. Seen in one light, this model is the reason why, years later, Matthew Inman can conjure up and banish the Blerch in a cartoon, or Alison Bechdel can wrestle with her father’s ambiguous influence by dressing in his clothes and drawing herself in the mirror. “The superheroes that are so intimately entwined with comics as a genre are, at heart, orphans and victims,” Kuskin says. For all the BAMs and POWs, their journeys are uniquely psychological. “One self has to transform visually into another self to survive, and that is what creators are doing every time they represent themselves in a panel.”

Though fascinating, these explanations didn’t entirely satisfy me—they seemed to be looking in on comics from the outside, instead of starting from the page. Even before I knew anything about cartoons’ subversive history, I still fell under the spell of dark, dreamlike worlds that swam around in my head; spiky portrayals of seizures; lonely rooms that embodied the depressive mindspace. (See, especially, Aidan Koch’s wanly lovely sequences in Blue Period.) The formal qualities of comics felt as crucial as anything to understanding the genre’s psychic eloquence.

Asked to weigh in on cartoons’ aesthetic properties, some of the fans I spoke to used phrases like “multimodal,” “many levels,” and “firing on all cylinders.” Comics combine the visceral punch of images—like, say, van Gogh’s wrenching self-portraits or these “Alzheimer’s drawings”—with the irresistible tug of narrative. They channel subjectivity (the precise way the light seems to warp around a crush’s face, the carbonated, cross-hatchy texture of mania) and rope it into the service of storytelling. Within each frame, you feel a character’s emotions acutely and often see through his eyes; at the same time, those frames melt into an arc that deepens and contextualizes its individual parts.

Top Shelf Productions

There are other advantages, too: Consider how ace comics are at displaying multiplicity. You can place simultaneous perspectives right next to each other, or use split screens to show two events happening at the same time. You can disrupt one narrative with the sudden intrusion of another. This jumble sometimes achieves the effect of Benjy’s chapters in The Sound and the Fury: a chaotic torrent of thoughts and voices. It can capture the whirl of consciousness as it interrupts itself, breaking a singular vision of the world into drifting pieces.

In turn, the strange, nonlinear juxtapositions that cartoons make possible ask something of the reader. They force her to weave connections that may or may not make sense. It is as if they are instructing her in the art of apophenia, or illusory pattern-finding. To a greater or lesser extent, every time you jump the gutter from one square to the next, not knowing exactly how the latter relates to the former, you perform the same sort of mental acrobatics that underlie metaphor creation, manic episodes, and schizophrenic delusions. Does this active reading process, this sense of scrambling for meaning, acquaint you with how it feels to go insane?

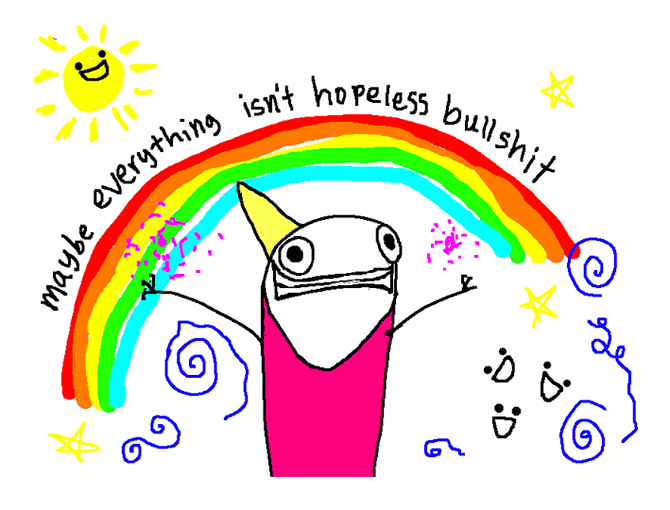

Another comics-wise friend of mine has a different theory on why the genre is so suited to representing psychological disturbance. An avid reader of mental illness narratives like Darkness Visible and The Bell Jar, she notes that books often cast these problems in a solemn, anguished, ethereally melancholy glow. Comics, though, can be refreshingly irreverent, funny, and un-self-serious (they’re called comics!). They seem more at liberty to capture the full range of something like depression—its battiness and bathos, how it can feel like waving around a bunch of dead fish—as well as its piercing edge.

Allie Brosh

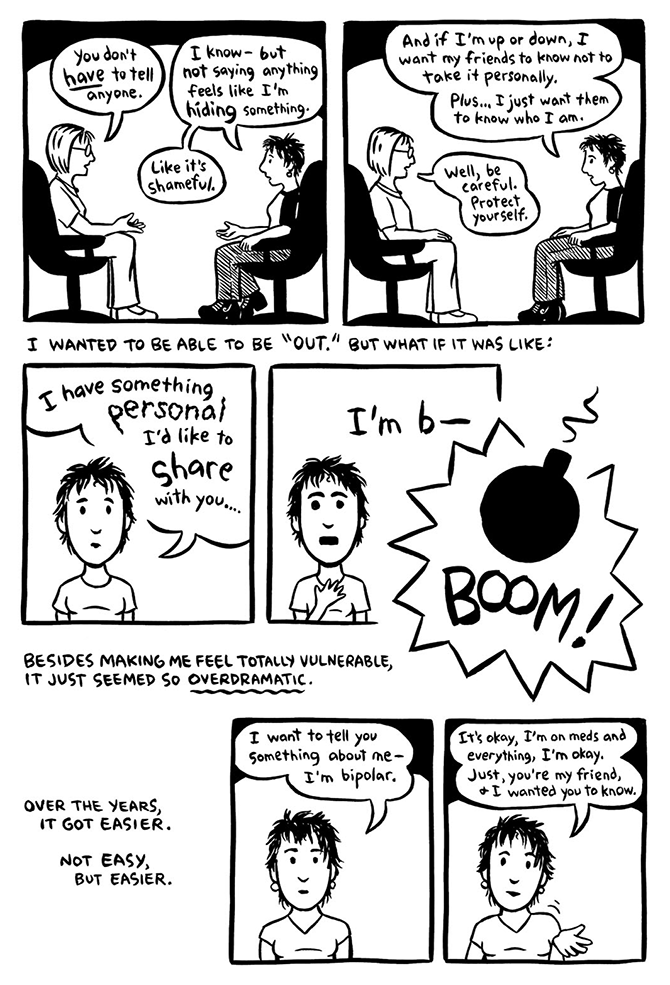

Ellen Forney helped clarify my mess of questions and impressions when I spoke to her on the phone. “Comics can give presence to tone and feeling and emotion in a way that’s difficult to do in other media,” she explained. “What happens with mental illness is that while there’s a lot of the story that is very specific—like text, which says a precise thing—there’s also a lot that’s really difficult to put into words. That’s where the language of comics comes in, the reliance on visual aspects that are strong in presenting mood.”

I asked for an example. “A comic that’s drawn dense and scribbly will come across as much darker in tone than something that is clean lines,” Forney said. “Those kinds of expressiveness are more visceral, like music.” Forney herself played with the abstract visual metaphor of the grid in Marbles. She used neat boxes to narrate her orderly therapy sessions, and loose, misshapen ones to convey the trapped feeling of a depressive episode. (The mania pages burst free of grids entirely.)

Penguin Press

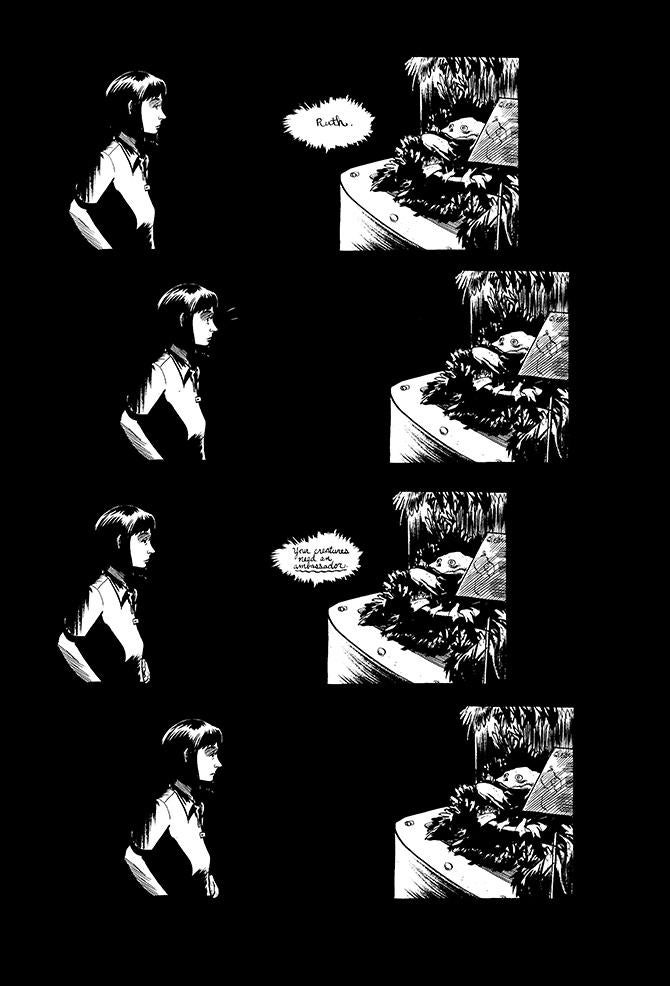

As I talked to Forney, I realized that working through a comic book reminds me of working through a poem. There’s an initial sense of disorganization and unfamiliarity, but then intuition seems to kick in. The structure may not be linear, but it still makes itself felt. In his essay on Shakespeare and depression, Jonathan Farmer writes that a good poem doesn’t “run like an aqueduct”—it meanders like a river. “Doubt,” he concludes, “is essential to poetry,” just as questioning your perceptions is fundamental to writing about your madness. Yet both madness and poetry offer their own bizarre scaffolds for experience. Powell gets at that, in Swallow Me Whole, when he uses the emotional logic of images to unfold one of Ruthie’s schizophrenic transports: She is scared, bugs are scary, and suddenly there they are, massing out of an air vent. Or think of David B. puppeteering the reader’s movement through Epileptic by alternating small consecutive squares with full-page boxes. You may feel as though you’ve passed outside of authorial control, but the comic is still pacing you, opening and contracting its world, shaping your responses.

Top Shelf Productions

What the loose but insistent truss-work of cartoons hints at is that mental illness is not structurelessness—instead, it requires you to make sense of a structure you don’t recognize. The structure is hard to describe because you probably don’t share it with anyone else. Maybe that’s the point of comics: to discover new forms of description, to find new ways to make sense of things.

—

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.