Slate is an online magazine, which means you are almost certainly reading this on a screen. It is more likely to be morning than evening. You are perhaps at work, chasing a piece of information rather than seeking to immerse yourself in a contemplative experience. You probably have other tabs open—you will flick to one if I go on too long. Your eyes may feel fatigued from the glow of the monitor, the strain of adjusting to Slate’s typeface, which differs slightly from where you just were. You should take a 20-second screen break if you’ve been gazing into your computer, smart phone, iPad, or e-reader for more than a half hour. I’ll wait. It’s OK if you don’t come back—we both know by now that most people won’t finish this article. If you do return, though, I’d like to bring up something that has been bothering me: reading insecurity.

It is becoming a cliché of conversations between twentysomethings (especially to the right of 25) that if you talk about books or articles or strung-together words long enough, someone will eventually wail plaintively: “I just can’t reeeeeaaad anymore.” The person will explain that the Internet has shot her attention span. She will tell you about how, when she was small, she could lose herself in a novel for hours, and now, all she can do is watch the tweets swim by like glittery fish in the river of time-she-will-never-get-back. You will begin to chafe at what sounds like a humblebrag—I was precocious and remain an intellectual at heart or I feel oppressed by my active participation in the cultural conversation—but then you will realize, with an ache of recognition, that you are in the same predicament. “Yes,” you will gush, overcome by possibly invented memories of afternoons whiled away under a tree with Robertson Davies. “What happened to me? How do I fight it? Where did my concentration—oooh, cheese.”

Reading insecurity. It is the subjective experience of thinking that you’re not getting as much from reading as you used to. It is setting aside an hour for that new book about mass hysteria in a high school and spending it instead on Facebook (scrolling dumbly through photos of people you barely remember from your high school). It is deploring your attention span and missing the flow, the trance, of entering a narrative world without bringing the real one along. It is realizing that if Virginia Woolf was correct to call heaven “one continuous unexhausted reading,” then goodbye, you have been kicked out of paradise.

And reading insecurity is everywhere, from the many colleagues who told me they have the condition (“My power to concentrate and absorb is atrophied. And that’s reading a short novel like Cat’s Cradle, which I’ve been reading for a year now”) to the desperate call-to-arms among twentysomething friends that rarely leads anywhere: “Let’s form a book club!” (Yeah, right.) An assortment of new reading apps advance the idea that we must reimagine reading if we’re going to salvage it, their fizzy positivism—Reading 1.0 is “inefficient” and “frustrating.” Reading 2.0 is great!—masking the same why isn’t-this-working anxiety. As a curative we have the unplugging movement. Books and articles probe the Way We Read Now: Teachers deplore it, kids seem unfazed by it, and millennials/late Gen Y-ers wonder whether to embrace or resist it. It is that last group—the ambivalent ones, who came of age just as the Internet was beginning to envelop society and can faintly remember glimmers of a prelapsarian past—that seems most susceptible to reading insecurity. Our nostalgia for print shades into nostalgia for childhood itself. We’ve landed in a different world from the one we started out in, but unlike our parents, we can’t retreat from it; we have to inherit it. We worry we’re not up to the task.

Science inflames this self-doubt, or at least reinforces the sense that something big has changed. A long train of studies suggests that people read the Internet differently than they read print. We skim and scan for the information we want, rather than starting at the beginning and plowing through to the end. Our eyes jump around, magnetized to links—they imply authority and importance—and short lines cocooned in white space. We’ll scroll if we have to, but we’d prefer not to. (Does the weightless descent invite a momentary disorientation, a lightheadedness? Or are we just lazy?) We read faster. “People tend not to read online in the traditional sense but rather to skim read, hop from one source to another, and ‘power browse,’ ” wrote psychologists Val Hooper and Channa Herath in June.

And it is not just the choreography of reading that changes when ink gives way to pixels. It is the way we experience, integrate, and remember the content. In her insightful (online) review of online and print-based reading styles for The New Yorker, Maria Konnikova describes a study by the Norwegian scientist Anne Mangen, who asked students to digest a short story either as a Kindle e-book or as a paperback. Despite the two texts’ physical resemblance—“Kindle e-ink is designed to mimic the printed page,” Konnikova notes—the students who read from the paperback volume could better reconstruct the story’s plot. Likewise, when volunteers were asked to write an essay on a narrative they’d consumed either online or on paper, those who had received tangible books crafted superior responses.

So maybe we’re right to be worried about our e-reading. Maybe we’ve sensed that we rely on physical cues to ground ourselves in complex arguments, and that we get more of those from books than from flickering screens. Online, the fugitive flow of pixels makes the ideas themselves seem airy and ephemeral. Are those wisps then less likely to lodge in memory?

The notion that language might absorb the evanescent or permanent properties of its medium was a big deal in the Middle Ages, as written records began to supplant spoken traditions. Chaucer linked oral expression to flux and deceit: In a poem that partially serves as a cautionary tale about rumor, he connects the transience of love to the vanishing sound of a lover’s voice professing it. (One character, for example, asks why guys lie so much when they pledge their faith out loud: “O have ye men swich goodlihede/ in speche, and never a deel of trouthe?”) Even earlier, the Roman poet Catullus sarcastically urged women to write their promises in wind and running water—media appropriate to the fickleness of their words.* Of St. Augustine, lifted to heaven by the concrete reality and inarguable verity of ink on codex (he converted after opening a Bible), Andrew Piper writes: “It was above all else the graspability of the book, its being ‘at hand,’ that allowed it to play such a pivotal role. …. The book’s graspability, in a material as well as a spiritual sense, is what endowed it with such immense power to radically alter our lives.”

Maybe this all seems somewhat egg-headed and wooly as an explanation for why Internet reading freaks us out, but I can’t help thinking that the hoary debate around “orality and literacy”—the slippery nature of one versus the stable authority of the other—is back, sort of. This time we’ve cast the new technology as the unreliable flibbertigibbet and the relic-like printed book as the trusty source. And after centuries of vaunting the solidity of written language, there’s a kind of whiplash in signing on and watching our literary output swoosh by.

Plus, and more prosaically, it is just much harder to concentrate when you read online. Email, IM, social media, and spiral-arms of infinite, alluring content are a click away. Once you pick a page, ads and hyperlinks beckon. In their 2014 paper, Hooper and Herath suggested that people’s comprehension suffered when they read the Internet because the barrage of extraneous stimuli interrupted the transfer of information from sensory to working memory, and from working to long-term memory. Experts have posited the extinction of the “deep reading brain” if we do not learn to tune out the Web’s distractions. (This is the kind of pronouncement that will make you sick with reading insecurity.) Some of my friends and colleagues say that they can feel their deep reading brains rallying if they boycott the Internet for a while, which at least implies that the syndrome is reversible. Yet most of our jobs in the information economy require a daily mind-meld with Dr. Google. Reading insecurity has a way of reminding you just how e-dependent you are.

For me, floating behind all the talk of our frazzled attention is a veil of guilt and blame: It’s your fault! You could sit down and do this if you wanted to. You could savor stuff on a screen—didn’t you just binge watch the entirety of High Maintenance last night? Yet the profusion of the Internet also changes the calculus of how long I’m willing to spend on a given story. I’m not alone: People report more impatience when they read from their computers. In reading as with everything else, we’re haunted by FOMO and the search for novelty: “We are sponges and we live in a world where the fire hose is always on,” wrote David Carr in the New York Times. Jakob Nielsen, who studies the mechanics of Internet perusal, put it more bluntly: “Users are selfish, lazy, and ruthless.”

So maybe the answer is just to close the laptop and read more books. Books! Hallelujah. Except that it sometimes feels as though we are Typhoid Marys, transferring our diseased Web habits back to print. A colleague around my age told me she now thinks of books as tabs: flitting distractedly between them, she is often forced to retrace her steps. I feel selfish, lazy, and ruthless even when met by the generosity of a sunny afternoon and a novel; sometimes I wonder whether a portal has permanently closed.

Yet the Web giveth, even as it taketh away. The good news is that, insecure or not, we are all reading more. Thanks to the Internet, words are everywhere; e-readers are light, slim, and cost-effective; our faster reading pace means we can range more widely. And yes, there are wonderful advantages to the onscreen reading experience, including searchable keywords, toolbars, the ability to look up anything. A different colleague, working on a historical project, raved to me about the obscure diaries he was able to unearth online—without the Web, he would have needed to travel to an archive in another state to find them, and would have had to scarf them down before the building closed at 5. The accessibility of the documents on the Internet, he explained, allowed for deep and prolonged engagement. And of course this was in addition to the breadth of knowledge afforded: You can’t overstate the vast contextualizing power of more than 1 billion websites.

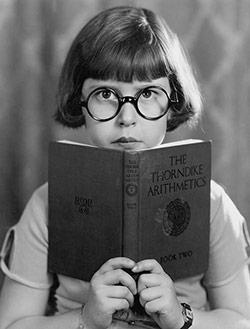

Everett Collection

I also realize, typing this confession of pathological distractibility, that I may be pining for an Eden of immersive focus that never existed. Did I ever really spend six hours with my face in a book? Was my imagination truly so unfettered from the concerns of everyday life—and, if so, isn’t that a childhood thing, not a technology thing? Twelve-year-old me never had a Google alert wrench her out of Francie’s Brooklyn so that she could write her roommate a check for the rent. She definitely wasn’t expected to know what was going on in Syria.

Still, the dissatisfaction lingers. In his 1988 study of ludic (or pleasure) reading, Victor Nell found that we read slower when we like a text. Our brains enter a state of arousal that resembles hypnosis. There is trance and transportation—which might explain why, 30 years later, adults prefer to encounter Darcy and Dracula offline, where they are less conditioned to skim, jump around, and be generally restless. In a recent survey of several hundred men and women over the age of 18, most respondents said they enjoyed print books more than e-books, though they were content to gather information from either format. The researchers suggested that pleasure reading requires a deeper engagement with the text, one facilitated by the kind of sustained, linear attention (and ability to annotate) that print books promote. In other words, when we bemoan that we don’t reeeeeaaad any more, we are mourning a specific kind of reading—and it is precisely this kind that seems to shimmer beyond our reach online.

This is not true for everyone. Not only do 52 percent of digital natives (at least, those of them ages 8 to 16, according to the National Literary Trust) prefer screens to spines, but their comprehension and recall doesn’t seem to vary depending on what reading technology they use. (Screw you, guys! I’m sorry, I didn’t mean that—I’m just insecure.) They appear to have mastered focus and self-monitoring skills in the age of Google. They take real joy in online reading, unmarred by uncertainty and shame. Their ease and comfort on the web implies that reading insecurity has less to do with technology per se than with the liminal status of a particular few generations, after Gen X and before the post-millennials, with one foot in the print world and another in the digital world, creatures fully of neither.

So where does this leave us twenty- and thirtysomethings with complexes? I would not turn back the clock on the Internet, obviously. I am not stupid enough to question the tremendous good it does, even if at times I stare at my computer screen and feel like a water strider posed tantalizingly atop a stream of inaccessible knowledge. (I would use a better metaphor, but it’s hard to wriiiite when you don’t reeeeeaaad.) It is encouraging that kids who grew up in a richly digital space seem to know how to navigate that space, and great that so many people have begun to reclaim reading. It is also tiresome to shake a fist at technology, and lovely to savor the fruits of our surpassingly verbal age. Online reading platforms, too, have social, economic, political, and aesthetic implications that I haven’t even begun to consider. The cost-benefit calculations are Gordian and vast. The ingenuity is staggering. Interactives are pretty! And yet. I worry that, over the past few years of living much of my life online, my relationship to text—especially the spacious, get-lost-in-it kind—has changed for the worse. It’s called reading insecurity. Do you have it?

Correction, Sept. 9, 2014: This article originally misidentified the Roman poet who urged women to write their promises in fleeting media. He was Catullus, not Horace. (Return.)

—

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.